British death metal icons Carcass are currently 35 years into their journey from minnows – yes, we love the Flesh Ripping Sonic Torment demo – to the foundational powerhouse we know (and love) today. Whether it’s the sickening (mentally and physically) feel get from debut Reek of Putrefaction (1988) or the quench we get from the death metal masterclass that is new album Torn Arteries (2021), Carcass has and continues to show their quality. It’s not just that either though. They aren’t merely showing their (de)compositional and music (s)playing capabilities — from “Exhume to Consume” and “Heartwork” to “Black Star” and “Cadaver Pouch Conveyor System” — but rather leading by their own example. Although members of Carcass will likely see things otherwise (read below), the Liverpudlians (and a Swede) charted their own course on their own terms early on. This is particularly true in the transition (or natural evolution) from the often-imitated, never replicated Symphonies of Sickness (1989) to the lighthouse, barfday boy album Necroticism – Descanting the Insalubrious (1991).

Today, Necroticism – Descanting the Insalubrious, with all its voluble verbiage, ruthlessness musicality, and then-prodigious production (courtesy of then-fledgling producer Colin Richardson), celebrates three fucking decades. Released by homebase label Earache in the U.K. and Earache/Relativity in the U.S. on October 30th, 1991, Carcass’ much-anticipated, nerd-splitting third album changed not only Carcass (in their ascent) but showed death metal – not grindcore (see below) – was ready for the very same thing that happened to thrash metal years earlier: refinement and growth. Pegged at the front by the dizzyingly merciless “Inpropagation” and plugged at the rear by the relentlessly cool “groove” / calculated blast of “Forensic Clinicism / The Sanguine Article,” Necroticism – Descanting the Insalubrious was honed for killing, even if the Jeff Walker-designed cover art rib-tickled otherwise. But Carcass weren’t just great at both ends. Inside the album’s rapidly hardening heart, tracks like “Incarnated Solvent Abuse,” “Corporal Jigsore Quandary,” and “Carneous Cacoffiny” were vying for attention while also signaling that the Britain-based outfit were rapidly becoming (or probably were then) a reckoning force.

It’s with profound (also salacious) pleasure and typical Decibel guts-flying-everywhere fanfare that we celebrate Necroticism – Descanting the Insalubrious as it turns 30. OK, we surrender to the fact that today is October 29th, 2021 – one day before the candles can officially be ignited – but that just demonstrates our eagerness, joy, and corrupt moral standing as we post fresh, positively rank interviews with none other than Jeff Walker, Bill Steer, and Michael Amott.

Talk to you guys in 10 years!

What was your initial reaction when I contacted you about Necroticism – Descanting the Insalubrious turning 30?

Jeff Walker: I groaned, I think. We did a piece with Decibel about Necroticism not that long ago [in 2005, perhaps – CD]. I wouldn’t have known it was the 30th anniversary unless I was told. I don’t really put too much credence into these types of things. I’m more about going forward with things. Actually, what I hate about the Internet is that there were tons of interviews with us about albums like Necroticism, and now they’re just gone. The archives and the things magazines have covered about us are really nowhere to be found. That’s a sad fact. I think this very interview will disappear in five years, and I’ll have to do a fucking interview with you for the 40th anniversary.

Bill Steer: I’m not particularly sentimental about the past. Besides the obvious stuff, the record has life in it. And that’s great! At the time and at that age, we were never looking any further than the next year. I don’t think we could [look beyond that]. So, with that said the 30th anniversary of Necroticism isn’t marked on my calendar. These days, it’s like constant reminders of how ancient I am. This interview is another! [Laughs] That said, it’s nice that the record is still being spoken about.

Michael Amott: It didn’t surprise me. I thought it would be older. [Laughs] I mean, we’re celebrating 25 years of Arch Enemy this year. Was it really just five years between that album and Arch Enemy? Back then, five years was forever. I was quite young when I quit Carcass. So, that’s weird. Now that I think of it there’s a lot of 30-year anniversaries coming up for a lot of classic albums. A lot of the death metal stuff. 1991 was a big wave year. Sepultura’s Arise comes to mind.

OK, do you remember how the songs came together? Ken was the riff engine of old, if I remember correctly.

Jeff Walker: I have to think back 30 years. I think Necroticism was written over a year or year and a half, which felt like forever back then. So, really, it was business as usual after Symphonies, I think. I view Necroticism as a continuation of Symphonies. The only difference was that Mike [Amott] had come on. And, you’re right, Ken was still writing songs or ideas for songs. Like “Symposium” is all Ken. For Necroticism, we deliberately wrote longer songs. I called them progressive before, but not in the traditional sense of progressive. The songs were actually a continuation from some of the songs on Symphonies [like on “Crepitating Bowel Erosion” and “Empathological Necroticism”]. The album was pretty much written before we went to America [with Death and Pestilence] in 1990. OK, now I’m starting to remember. I think with this album, we started to shift away from Ken, actually. The last few songs we wrote – “Corporal Jigsore Quandary” and “Incarnated Solvent Abuse” – were without a lot of input from Ken. We either stopped using his riffs or had totally exhausted what he had written. Anyway, those songs were shorter and kind of became the album singles. Writing long songs for a year and a half started to wear on us. That’s how “Corporal Jigsore Quandary” and “Incarnated Solvent Abuse” came to be. Actually, they’re not that short after all, so what do I know?

Bill Steer: With Necroticism, we brought Mike onboard, and the stuff he contributed was brilliant. The way I remember it, “Incarnate” is mostly his with a section or two in the middle from me. But Mike became Carcass-ized on that song. Jeff has very strong opinions on arrangements and the way Ken plays, songs often come out the other end very different. That would go for all the tunes I brought in as well. I do remember Ken was still very much involved as well. “Symposium of Sickness” is basically all Ken, so his fingerprints were all over the album. We were still rehearsing in my parent’s attic at the time. In that way, Necroticism was no different from the previous two albums. Often, it would be just Ken and myself. Jeff would come along quite often. In Mike’s case, he’d come to the UK when we had work to do. He wasn’t actually living in the UK then. Sometimes, he’d come over and tunes would change shape, but more often he was good at adapting to us. He really dove in.

Michael Amott: Well, I joined in April 1990. I remember playing guitar with Bill. We’d play all day. We’d go down to the kitchen, get something to eat and go back up and play more guitar. We were relentless. We developed a lot too. I think Bill enjoyed having a second guitar player. I could play what he showed me, which allowed him to do stuff on top of that. That was a first for him that he could bounce ideas off of and jam with [another player]. It was fun. It was a young and innocent time for us. The first thing I did with Carcass was tour for Symphonies in Europe and the states. They already had songs or parts of songs already completed when I joined. The technical stuff, I think. The deep album cuts – the 7-minute cuts – were already being worked by Ken and Bill. They were in demo shape. I think after the touring of Europe and America we realized the very blasty stuff with lots of riffs didn’t go down as well as we would’ve hoped. As a result, we streamlined the songs a little bit. Necroticism is definitely shaped by the responses we got from touring for Symphonies. That’s the way it usually goes. But now that I’m saying this, the first song on the album [“Inpropagation”] has a lot of riffs. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. I had one riff – the melodic breakdown riff – in “Corporal Jigsore Quandary” and most of the ideas for “Incarnated Solvent Abuse.” I brought in my different influences. I was into more melodic music, which is now my signature style. That was outside the box for Carcass. Bill had a riff in that too. That song became the lead-off track. We shot a video for it and everything. I couldn’t believe it at the time. I thought they’d hide my track way at the end of Necroticism. [Laughs]

Was there intent to be less musically grind/churn-oriented?

Jeff Walker: No, it’s a continuation of Symphonies. That’s all it is. We had better equipment and a better production. We sounded better. That’s all it is. Stylistically, I don’t think we changed that much. Maybe Mike brought in some borderline Megadeth riffs on “Incarnated,” but there’s nothing deliberate in Necroticism. There’s no more melody on Necroticism than there is on Symphonies. Maybe there’s more major key shit happening. Twisted major key stuff. If what you’re describing is present on Necroticism, then it was all by continuation of what we had previously done.

Bill Steer: Definitely, it was down to the way we were evolving. We have albums before Necroticism that are dark and churning. We were probably 20-21, so we were starting to open up to the idea that bringing in other elements to this music was acceptable. Also, we’d come off the big tour in the U.S. with Death and Pestilence. Both bands were far superior players. That gave us a vision of where we could go with Carcass.

Michael Amott: I wasn’t the musical director of Carcass. Bill was. I showed them a couple of riffs I had written for them in 1990. That summer, I think. I showed them to Bill and he said, “Uh, no. They sound like riffs we had done in the past.” I was like, “Shit!” That made me think of where things were going. Just a continuum of things or… I wasn’t completely sure. I didn’t really submit ideas for a while. Until I submitted the riff to “Corporal Jigsore Quandary” and the main parts for “Incarnated Solvent Abuse,” actually. Then, it was thumbs up. I ended up submitting more and more ideas for the next album, Heartwork. My relationship with them had become more solidified by then for sure.

Jeff Walker: They’re the shorter songs. They’re more immediate. Back then, every second costed a lot of money, especially with music videos. Labels like Earache didn’t have a lot of money for music videos, and if they did they didn’t really want to invest money – many thousands! – into music videos. The money was basically coming out of our pockets. So, we had to make videos on really tight budgets. Major labels were a different story. They poured money into music videos. And let’s be honest, most bands aren’t going to release a 10-minute music video. Casual listeners or watchers aren’t going to sit down for 10 minutes for a music video. So, in the end, they’re catchy and short. Perfect for the format. The “Incarnated” video was off-the-wall. It was done cheaply and it’s stupid. Though, I will say the video imprinted on people. I still get questions about it. And, yes, I wish we would’ve played more to what the director [Steve Mallet] wanted. “Corporal” was just video footage from the Astoria show. At the end of the day, we’re a band. We make music. We’re not performers.

Michael Amott: I can’t imagine the director went on to great things. [Laughs] It was kind of psychedelic, but that’s probably because we didn’t really have a budget. I remember him saying to me, “OK, stand on this Marshall cab. You’ll have white body paint all over you.” I was like, “Yeah!” I was down for anything at the time. It was my first-ever music video. I think he shot with 16 mm film. No green screens, if I remember. Just a big white room. It was done in London. I remember after the video – it was a very long day – we stopped for a meal. Ken was the only one with a driver’s license. We were in van. Anyway, we had our Indian food, and when we left we discovered the van had been impounded, towed away. We had to go and pick it up. Such a hassle. The video ended on a bum note. [Laughs] The video got a lot of airplay on the metal shows in Europe though. Headbangers Ball in Europe played it a lot. We became mainstays. We’d host the shows. They’d come out to our shows as guests. They latched on to the death metal boom for sure. If we didn’t have that video, Necroticism wouldn’t have been as big.

Bill Steer: I don’t have a strong memory of this. I think the video choices were ours. Earache never really interfered with what we wanted to do conceptually. There’s one exception. The cover of Symphonies. Originally, it was going to be the stuff that you see on the inside of the gatefold. They made a reasonable point though. If we kept the cover as-is it wouldn’t look any different from the previous album cover at a distance. That’s how the Symphonies cover and gatefold ended up. Other than that, I don’t remember Earache suggesting anything creatively different to us. The video [for “Incarnated”], we hated. It was beyond embarrassing. We were kind of thrown to the lions with that video. We didn’t know the director at all, so it was more like a random hookup. Hearing that he worked with Cathedral makes sense, but all I know is they got off lightly. [Laughs] I was relieved I was pretty much left out of the whole thing. To this day, I don’t know why but I’m grateful.

Interesting you [Jeff] mentioned the songs were more progressive. They weren’t ELP or Yes progressive, but they did challenge the Carcass status quo. Necroticism bookends with two of the album’s longest songs, “Inpropagation” and “Forensic Clinicism / The Sanguine Article.” I remember hearing them and thinking, “Yeah, I’m way into this.”

Jeff Walker: Well, remember we never really wrote songs in Carcass. Our songs previous to Necroticism were more like a bunch of riffs. That was our attitude. They were more like musical pieces with lyrics put on them. Things were never repeated in a traditional verse-chorus sense. I always used to think that was lazy. Or, maybe I just had too much to say, and the traditional verse-chorus format didn’t really suit what I had to say? A weird opera, in a way.

Bill Steer: I always hesitate to use the word ‘progressive.’ If anyone applies it to us, I kind of shiver. It’s not a negative word, but it has connotations. There’s no doubt about it — we were pushing forward. We wanted to show that we had more to offer musically. I think we were nervous about being swamped by bands doing similar things. When we made Symphonies, I remember we were really happy with how it turned out. It didn’t take too long that we were hearing recordings – mostly demos – from bands that were doing similar work. We didn’t want to get lost in that. It’s claustrophobic, really. So, I think when we heard all that, we pushed against it pretty hard. That was a period where the sky was the limit arrangement-wise, and obviously, none of our stuff is typically verse-chorus, so we had a lot of room to push and experiment. I think that was the peak of us going nuts musically. The first song [“Inpropagation”] has so many parts I can’t really remember them all. [Laughs] There’s a lot of twists and turns in that song that we never really went back to.

You [Jeff] say opera. The lyrics were very involved. The terms you used were uncommon, if archaic. I always thought that decoding the lyrics—however gross—was part of the puzzle with Necroticism. They were like an intricate story. There was some level of masochism to deciphering Carcass.

Jeff Walker: I toiled over the lyrics on Necroticism. I spent a long time tweaking them. I took that part of my role seriously. The lyrics were never targeted at anybody. We wrote what we were interested in. They had a limited appeal as a result. They’re so niche. Pop music lyrics are lowest common denominator, and my lyrics are not. They appeal to a certain audience. Limiting ourselves was kind of cool. I sort of feel awkward about that now.

Bill Steer: Once Jeff had established the lyrics as his domain, we left him to it. Initially, it was quite an even mix between the three of us. Like the music on the first album. Ken was the first to write lyrics for Carcass. He was writing lyrics before Carcass even existed. I encouraged him to work those into Carcass. I was inspired by him. I also thought what he was doing was funny. It was poetic in a way. By Necroticism though, it was all Jeff.

People equate Carcass lyrics with needing a dictionary or thesaurus. The terms were always challenging. For me, you were adding to the mystery of the subject matter, which included the music.

Jeff Walker: That was deliberate. There are only so many words in everyday use. We were trying to do something different. I was always looking for better adjectives to words I’ve used a hundred times.

Bill Steer: Jeff had gone deeper into the dictionary and thesaurus than we ever had or ever will. [Laughs]

The title was clever. “Necroticism” is a neat portmanteau of necrosis and eroticism. “Descanting the Insalubrious” is the discussion of ill-health of others in a verbose way. It’s all very gross and fitting but in a collegiate, deliberately opaque way.

Jeff Walker: Ken came up with the “Descanting the Insalubrious” part. I came up with the “Necroticism” part. Really, the title is a compromise. That’s how we ended up with this long album title. Some of the music is compromise. To me, compromise always pans out.

Bill Steer: That’s exactly right. Ken and I wanted his phrase. Bill wanted his phrase. In the end, we said, “Let’s just make it one phrase and that’ll be the album title.” It’s a very ungainly title. But it happened. We can never take it back. [Laughs]

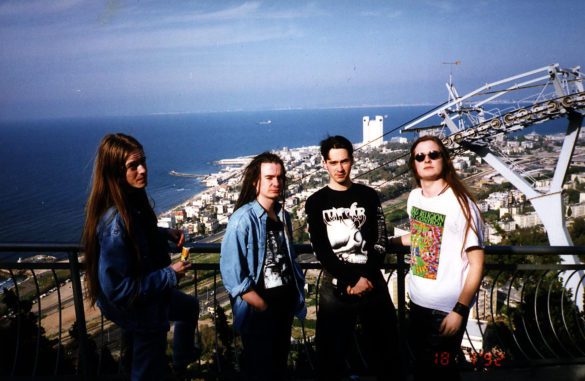

Photo by Michael Amott

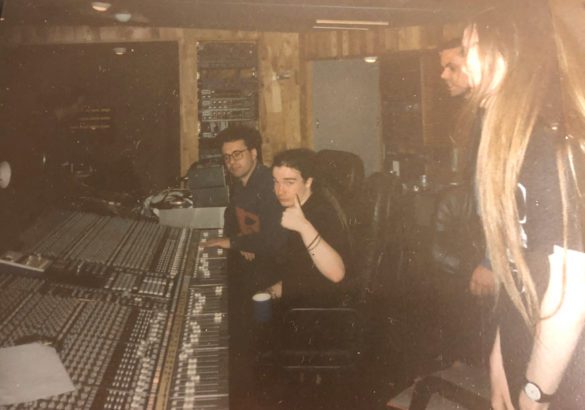

What do you remember going into Amazon [Studios] to record?

Jeff Walker: It was good times. A nice studio out in the middle of nowhere. We used to drive out every day. The studio was right on the edge of Liverpool, maybe six miles. Bill and Ken lived in Wirral, which made it a 15-mile journey. I remember we were up against the wall, to a certain extent. We were using our own money to fund the recording. We were out of contract with Earache at the time. We plowed 20 grand of our own money into the recording. That was a lot of money back then. And not to mention for a band like Carcass. I think we ran out of money just as I was starting to track my bass. It was a labor of love. We were prepared to spend or blow our own damned money to get the thing made and released. Some label, in the end, would’ve picked it up. That’s what we thought going into the recordings. We weren’t concerned about that. We had the strength of our own convictions going for us. My memories of recording there are pretty hazy though.

Bill Steer: We really felt like we were going up a notch. The studio was really nice. For example, an album like Headless Cross had been done there. That meant something to us. I don’t remember how much deliberation went into us choosing Amazon, but I think it might go back to the song [“Exhume to Consume”] we recorded there for the Grindcrusher compilation. I think it just made sense for us to recording locally. That way we could go back to our own beds at night. Plus, in our minds, that choice meant that it would probably be cheaper overall.

Michael Amott: I remember the reviews were great! Most critics cited the improved production as one of the reasons for liking the album, but if I listen to it now, it doesn’t really sound that great. At the time, it was difficult to get clarity. Back then, everyone was so tired of productions sounding like shit. So, we had that going for us on Necroticism. Now, it’s the opposite. Everyone wants to have a shitty production. [Laughs] At the time, we wanted people to hear what we were playing. We thought that would be cool.

Colin Richardson produced. Keith Hartley, Dave Buchmann, and Ian McFarlane engineered. What comes to mind when I mention those guys?

Jeff Walker: I occasionally bump into Ian. Ian was a tea boy. He cleaned the tape heads and made tea. He didn’t know anything about engineering. Keith, god there’s a name. I spent a lot of time working with Dave in another studio. We made those sequencing pieces or segues that you hear on the album. We were in the demo studio, I think. The studio never charged us for those things. They probably didn’t realize I was in there doing it. I remember Dave was very enthusiastic. He didn’t really care if he was getting paid. He just wanted to be involved.

Bill Steer: Goodness. Fond memories for sure. They were all lovely people in different ways. From what I understand, Dave is no longer with us. Dave was one of the most sincere, straight-ahead characters that we had ever dealt with in a studio. He was thoughtful and super-intelligent. A lot of the time people back then were respectful of us, but you could tell there was disdain for the music. They couldn’t stand it. That was common for a band like Carcass or Napalm [Death]. Keith was enjoyable as well, but he didn’t enjoy our music full stop. He was a likeable chap even so. He’d make a suggestion every now and again. Good suggestions. Ian was the guy we loved hanging out with. He was very funny. He was more than a tea boy though. He had a zest for life. Not everyone in this band has that. So, Ian was pretty energizing.

The voice-over segues added a lot to the songs. They gave Necroticism a documentary or filmic quality. Where did the idea – to add them in context of the music – come from?

Jeff Walker: That’s hard to pin down. Maybe The Who’s The Who Sell Out. Or, Crass’ Christ – The Album. Or, The Crucifucks’ self-titled. The three records I mentioned probably contributed to my thought process at the time. So, a few bands had done that before. I thought it would be cool to make Necroticism one long musical journey than an album with all the stops. There’s a more cinematic quality, I think. You listen to a record for the music, but these pieces made it more like a film. As I said, this is our progressive album. Which has made people think that I’m insinuating that we were trying to be King Crimson – far from it, actually – but we were trying to be progressive. The album is genuinely a progressive album. It’s taking our ideas to another level. I mean, for the time we had classical influences, keyboards, acoustic guitars, and samples, which was cutting edge. In that sense, it’s a progressive album. It sounds absurd to say that now because it’s 30 years old. Now, it’s a classic rock album. [Laughs]

engineer Keith Hartley, Bill Steer. Amazon Studios 1991.

Photo by Michael Amott

Let’s go back to Colin Richardson. You continued working with him after Symphonies. What was your working relationship like?

Jeff Walker: We were the first band to take him out of [The] Slaughterhouse [in Driffield], which was the studio where we did Symphonies. He was the house engineer. I think the story is that studio burned down and he was, as a result, out of a job. We were the first band to hire him and get him in another studio. We gave him the job of producer, and you can see where his career went after that. He was great to work with.

Bill Steer: Colin’s producer cred was just starting. He was involved in Napalm’s Mentally Murdered first. Shortly after that, he did Symphonies. That might’ve been the first time he was credited as a producer. Before that, he was just a hard-working engineer. Sometimes his name wouldn’t even appear on records. So, word got around that he was somebody who was really diligent and took the music reasonably seriously. That was very rare for bands like Carcass in the UK. Primarily, Colin was an engineer who took the whole thing very seriously. He gave it more energy and focus. All of a sudden, the whole thing was raised a lot. He would always find a way to get us out of situations that were musically risky. So, in our world that’s what a producer does. But in music history, a producer is more into arrangements and people’s performances. This is metal music so things are always different.

Michael Amott: I wasn’t super-involved. Bill played all the rhythm sections. Just like I do with Arch Enemy. Just like [James] Hetfield does in Metallica. That’s just to get everything super-tight. I did throw my leads down. That I remember. Working with Colin was fun. The studio was a lot fun, just to hang out in. Remember, we were like 20-21 years old at the time. We were children in a professional studio doing adult things in a recording studio. I think Black Sabbath did something for Headless Cross in that studio. It’s like, “Holy shit! I’m sitting on the same couch as Tony Iommi!” That was so cool to me. I had been in the same studio as Entombed, but I shared a rehearsal room with Entombed, so it wasn’t nearly as impressive. [Laughs]

Did Carcass have a different production blueprint for Necroticism?

Jeff Walker: Symphonies didn’t turn out how anybody wanted. The limitations of money, technology, and knowledge were all part of that record. Nobody had a clear vision of what that record was going to sound like. We were probably pointing to King Diamond’s Conspiracy, something as slick as that. Obviously, that never panned out. Back then, it was very difficult to go into a studio with some money and come out the other end with a decent sounding album. That’s why so many albums don’t sound necessarily great. Today, there’s consistency in technology, and everyone’s doing it using software that they can control to a great degree. Symphonies was done in a real studio, with real microphones, on tape. There weren’t hundreds of guitar amps that sounded like EVHs. We didn’t go into Amazon with a choice of 10 different amps. We had to use what we had. We were really happy with the way Necroticism turned out.

Michael Amott: There were two Amazon studios, actually. When we did the Heartwork album, they had opened another Amazon studio in Liverpool. That eventually became or was renamed Parr Street Studios. Necroticism was recorded at Amazon in Kirkby. Colin first came down to Liverpool to listen to us rehearse and talk about where we wanted to go sonically. I remember Bill playing a bunch of records that he was into from his bedroom. The process was fun, exciting to be in a studio like that.

Bill Steer: We probably played stuff for Colin, yes. But that was destined to be ill-fated. Those things rarely turn out well. One of the albums we were listening to a lot in the van was Thin Lizzy’s Thunder and Lightning. If we had played any album for Colin, it would’ve been that one, and that would’ve been preposterous since the dynamics on Thunder and Lightning are vastly different from Carcass. The guitar tunings are different. Nothing matches up! Maybe we were looking for where we were at mentally. A zone-type thing that we wanted in the recording.

You [Jeff] mentioned Carcass was out of a contract. What pushed you back to Earache?

Jeff Walker: We were shopping it around. Earache made the best offer. I remember we spoke to Roadrunner and their offer – which I still have somewhere – was pretty typical of the time. Meaning, crappy and laughable. The percentages were tiny compared to what we were used to. We spoke to the guy – not Monte [Conner] – who was interested in us, and he said, “Well, you can’t sell a lot of records and be successful and make a lot of money.” The choice was: have income or be famous. I think we thought we’d rather have the best of both of those worlds, and that’s why we went back to Earache. We just plodded on after that.

Brand recognition was part of the experience. The continuity between Symphonies and Necroticism could’ve been broken had you gone to another label. That Earache logo meant a lot to us back then.

Jeff Walker: Not of quality but continuity. [Laughs] Well, it was a golden period of time for Earache. I’m kind of glad it came out on Earache.

Bill Steer: You’re dead right. From this vantage point, I can see that. At the time, this wasn’t entirely clear to us. The record-buying person wants continuity. I bought a lot of records that were on the Music for Nations label. At the same time, I probably read interviews with my favorite artists that had terrible relationships with their label boss at Music for Nations. That didn’t mean much to me. I wasn’t experiencing the same things those artists were. I only cared about the things that I liked. Before that, the same goes for Neat Records and Heavy Metal Records.

Tell me how the cover art came to be. It’s a photograph. Again, there’s a filmic — not a cartoon or comic book — take on the visual aesthetic.

Jeff Walker: I think everything on this record is the result of accidental success. There’s no storyboard for Necroticism. We wrote the riffs, beats, and lyrics, but everything else was chance. The stars aligned a bit for us. The album was kind of thrown together. I don’t mean to say we didn’t give a shit. What I mean is the composition was very spontaneous. The idea to do the individual group photos was planned out, but we didn’t really know what we were going to do with them. The final cover piece was shot in Ken’s dad’s veterinary surgery room. The composition was made up on the spot. I must’ve had a vague idea of what I wanted, but I do think we were lucky with the way it all came together. There were so many things we did on-the-fly and off-the-cuff. The cover wasn’t as premeditated as one would imagine. OK, I did come up with the hammer. [Laughs] We worked with a guy named Ian Tilton. He’s a brilliant photographer. He actually took the individual photos of us, which I think were meant for Sounds. To be honest, I wanted a 4AD-type cover for Necroticism not the typical death metal cover. That’s all pretentious bullshit now, but we were going for it. Typical of the ‘90s, I think.

Bill Steer: I think the hand with the hammer is Ken’s. After all, it was a surgery room that his dad had. His dad was kind enough to let us use that room.

Michael Amott: I wasn’t there that day. It’s a very different cover. I wasn’t sure what to think of it at the time. It’s just a photograph. It didn’t really strike me as an album cover image. Maybe if it had been treated a different way. Maybe it was too realistic. It’s a lot less gory. The approach is a bit more refined. They wanted the artwork to reflect the music. They hated all that fantasy/Dungeons & Dragons stuff. I liked all that. They weren’t into zombies either. They weren’t into the comic book/death metal look. I didn’t have a problem with that at all. That’s why I kept my mouth shut. [Laughs]

There are things that are asymmetrical to the medical profession or industry in that cover. The hammer, for example. Also, the arm hanging out of the trashcan.

Jeff Walker: That’s all deliberate. A joke. The arm was, I’m pretty sure, mine. This is the thing about memory and time, but Tilton is convinced the arm was his assistant’s. That was my idea. I saw the bin there, so I thought it’d be easy to make it look like someone’s in the bin. OK, now you’re making me think the crux of what we’re discussing was just a big gamble. The music was locked down. Everything around it was aligning of the stars. Even if the production failed at the last hurdle, people liked it. It sounded good for the time. Obviously, it could’ve all gone the other way, and we would’ve had another Reek. [Laughs]

Bill Steer: That was all Jeff. We were all there, but Jeff drove everything with that cover. We could tell it was going to be a new chapter musically, and the cover needed to reflect that.

What do you remember about touring for Necroticism? The Gods of Grind in Europe and the Campaign for Musical Destruction in the U.S.

Jeff Walker: We did a UK tour, which went pretty good, if I recall. The Marquee [Club] was sold out. On that tour, we were sleeping at our then-manager [Martin Nesbitt] sister’s house in London. He came up with the line, “Guys, you’re gonna have to buy better sleeping bags.” That was his idea of success for us. The European tour was with Entombed and Cathedral. That was the Gods of Grind tour. That must’ve been 1992. Then, we went to the U.S. for the Campaign tour. That was the only time we came to the states [for Necroticism], if I remember right. We did play Spain and Italy. We didn’t really tour back then in all honesty. There were no festivals to play.

Michael Amott: The Gods of Grind was great! I already knew most of the bands on that tour, except for Confessor. They were really nice guys. They never went down very well. Musically and vocally, the time wasn’t right for them. I’m still certain the time has yet to come for Confessor. [Laughs] I liked them. I knew the Entombed guys – Nicke [Andersson] and L-G [Petrov] – from the late ‘80s, so that was pretty fun. We were young and did stupid shit. It was great!

Bill Steer: The Gods of Grind just came up in an interview last week. The name of the tour had nothing to do with the bands involved. No band on that tour was grindcore. That was a marketing thing. As far as I know, Mick Harris coined that term, and used it relentlessly. Then, Digby [Pearson] at Earache kind of jumped on that. Suddenly, we had everything grind in it — Grindcrusher, Gods of Grind, etc. As the years go by, people would label bands from that era grindcore when it was really only Napalm that had that tag at the time. I used to get questions all the time about Carcass not playing grindcore anymore. Well, I always hate to disappoint people, but we weren’t aware that we ever had been grindcore. [Laughs] I don’t know what I would describe the early stuff as. We were influenced by death metal. Grindcore was Mick Harris’ term. It’s amazing to think his time in this music was brief, but his impact has been enormous. For us to use that term to describe us would’ve been incredibly cheeky. Now, people are quite religious about the term.

I missed the Campaign for Musical Destruction tour because the venue [Harpo’s] wasn’t all ages. I was gutted.

Jeff Walker: We played Harpo’s right? Yeah, well, we toured in a van. We had 24-hour drives and bullshit like that. That was a fun tour. I don’t remember anything specific. I’m not like David Coverdale who has all these anecdotes that he can pull out of his ass.

Bill Steer: Again, that’s pretty hazy really. I do remember Harpo’s. That stage was so high up and the venue so large that it was kind of hard to relate to the audience. I remember playing Chicago more specifically though. We were all outside chatting, and one of the Trouble guys comes up to us. Napalm had just hit the stage, and the second the vocals started, this fellow from Trouble was completely gobsmacked. He said, “Are these the actual vocals for this band?” We all said, “Yes.” He paused and then chuckled, “Oh, that’s awesome!” He had obviously never been exposed to this style of music before.

Necroticism has become synonymous with quality and innovation. The album showed death metal could be sophisticated. What do you make of people who come up to or tell you Necroticism is great?

Jeff Walker: Obviously, I’m flattered. There’s an incredible amount of conceit, narcissism, and egotism that goes into making music. There’s a lot of self-belief. It’s payoff for your own belief. Like I said, we paid for it with our own money. We were up our own asses to believe in it — that what we were doing was important enough to document on tape. So, it’s cool when people say that the album is this or that. I personally don’t get it when people say it’s our best album. It is what it is. I guess what I’m trying to say is it’s not so surprising that you’re so conceited that you believed in your own bullshit. When you’re that young, you do. If you don’t have that kind of self-belief, then you wouldn’t be doing it. You wouldn’t be on stage making a dick of yourself. Basically, it’s just rewards for what we invested in it. I don’t listen to the album, but I understand why people still do. There’s a lot of nostalgia built into it. So, I’ll thank them now, but I don’t buy into it. I get no emotional satisfaction out of it.

Bill Steer: It’s lovely! We were trying so hard back then. There was enough self-criticism going on to understand that we weren’t quite reaching the targets that we had set for ourselves. We had set the targets very high. Our playing ability wasn’t quite there yet, but we were still striving. That’s the main thing I remember from those days. I think we didn’t really like what we got out of the studio. Content-wise, yes. Sound-wise, maybe not. Regardless of what people think of the next album Heartwork that really is the sound that we had been after for a long time. Necroticism was just a few steps away from that.

Michael Amott: To be honest, it doesn’t really happen anymore. Plus, the people who are still into that record aren’t allowed to go to shows anymore. [Laughs] Fifteen years ago – the early 2000s – I’d get that more. This is true when I started going back to America with Arch Enemy. Now, I think we’ve bummed out the Carcass fans so much with our music, they don’t show up anymore. [Laughs] OK, it’s still here and there. I’ll always be grateful for Carcass. It changed my life. I can’t thank Jeff, Bill, and Ken enough for bringing me in. It was so cool of them.

Projection time. Do you think we’ll be talking about Necroticism 10 years from now?

Bill Steer: Good question. I genuinely don’t know. I think it’s absolutely remarkable that we’re talking about it right now. Musical trends come and go. So, I don’t want to predict the future, ’cause I’ve always failed at that.

Jeff Walker: Like I said before, the Internet will “lose” this interview like all the others. You’ll probably be asking me the same questions. Or, Albert will hire me to answer my own questions. [Laughs] But I get it. The album is a product of its time. The people who are going to get wet about this interview have so many memories from that period in time. I think the younger people who read this – there’s going to be one or two literally – aren’t going to understand the people who were there at the time and what they got from Necroticism.

Michael Amott: Well, the last time I listened to Necroticism was the remasters, which was like 13 years ago. But 40 years? I can’t even imagine that now. I will say, the narrative we had in the band at the time was that this was here-and-now music. It wasn’t meant to be remembered. That it’ll never be classic. Nobody was going to remember all these shitty death metal bands, including us. We did put a lot of effort into the album. Jeff, Bill, and Ken were very brainy about everything. I learned to put a lot effort into the records I’m making from them. It’s only done until it’s done. Also, you have to remember that the first Iron Maiden record or Mob Rules were only like 10 years old when Necroticism came out. They were mega-classics at the time! So, it’s weird to place Necroticism against bonafide classics. We never thought it’d be a classic. It’s not up to us as artists which albums become classics. That’s up to fans, gatekeepers, and tastemakers.

Carcass links:

1. Decibel September 2005 [#011]. Massive Carcass Necroticism Hall of Fame! LINK.

2. Carcass Shop @ Bandcamp. LINK.

3. Facebook. LINK.

4. Instagram. LINK.

5. YouTube. LINK.

More 30th Anniversary Interviews::

1. Death – Human. LINK.

2. Suffocation – Effigy of the Forgotten. LINK.

3. Immolation – Dawn of Possession. LINK.

4. Dismember – Like an Ever Flowing Stream. LINK.

5. Autopsy – Mental Funeral. LINK.