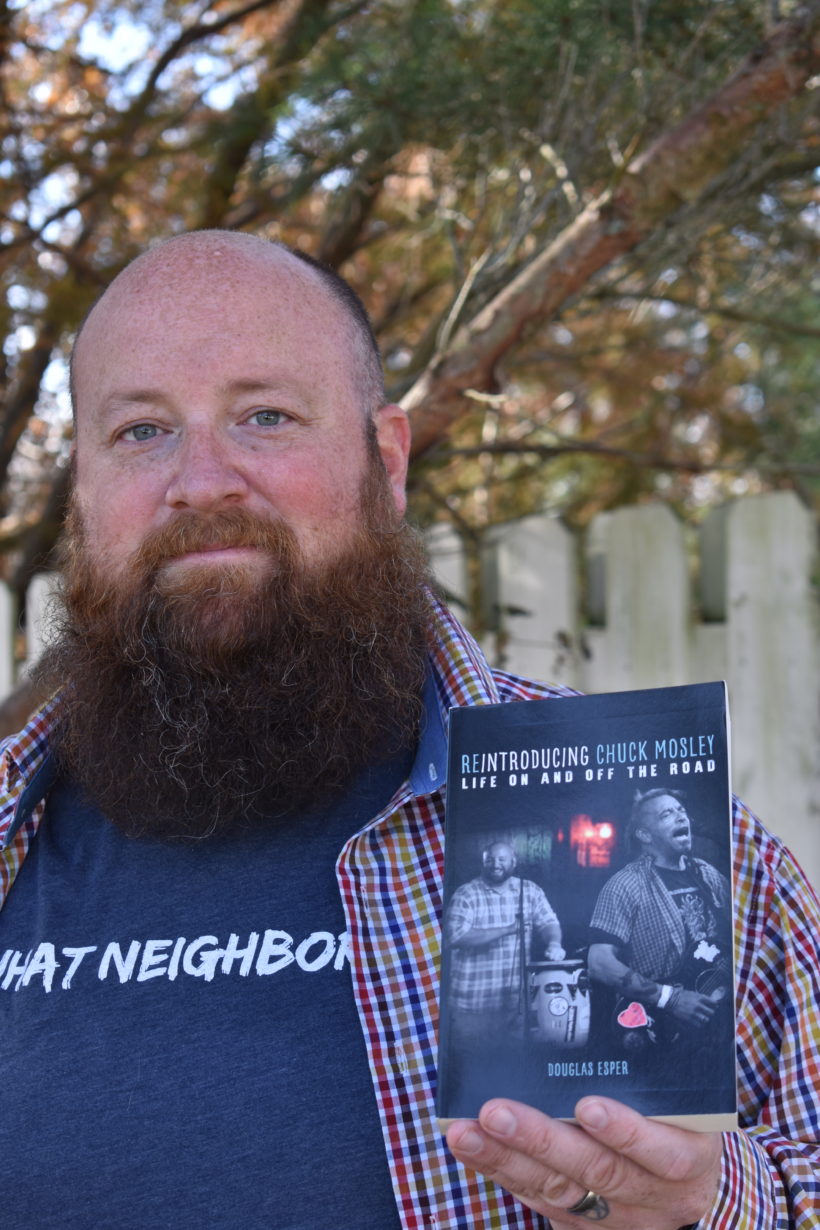

We all know Chuck Mosley as the guy who sung on the first two Faith No More records; some of us may have heard his band Cement, or have a vague idea that he sung for Bad Brains for a while, although, if we’re being honest, much of Mosley’s non-FNM output remains an obscure mystery, as does the man himself. Douglas Esper’s new book Reintroducing Chuck Mosley: Life On and Off the Road (published by Scout Media) aims to change that.

Mosley died in November 2017; this book offers a fascinating glimpse into a fascinating mind. We caught up with Esper to talk about the book and to get a bit more insight into who Mosley really was.

What makes Chuck’s story interesting enough to warrant a book?

Chuck loved and encouraged rumors and legends and lies to spin around him as the only source of insight into his life. He enjoyed leaving things mysterious and vague. That way he was able to be a character onstage. This has its positives and negatives, as sometimes rumors can grow into nasty things. I thought an honest, open unflattering look into his life might interest people who have only known him through clickbait articles and decades-old falsehoods. Aside from Chuck fans, though, I think his story will resonate with people interested in indie touring, writing and recording music, travel and a general desire to learn about a talented yet troubled soul.

When did the idea of this book first come to you, and why?

I actually tried for years to make progress on an autobiography with Chuck, so the idea goes back to when I met him in 1997. We made little progress, but I continued to note various milestones, good and bad, along the way. As we started to tour in 2016, I took notes for the book almost daily. When we finished touring in November of 2016, I wrote two chapters of the book, one detailing his reunion with Faith No More and another about our first tour leg that stretched across the country. I made a query letter, an outline, and gathered info to pitch the idea to agents and publishers, but didn’t find any interest. At that point, I thought the touring might be done, but we decided to go out again in 2017. As we wrapped up the 2017 dates, in November Chuck and I agreed to publish a book via a small publisher a friend of ours had worked with in the past. A few days later, Chuck was gone. The publisher asked me my plans and I told them I wanted to see the book through, although obviously it would need to change to my point of view. I started revamping and writing the rest of the book that day and finished around May of 2018. Chuck fascinates me musically and personally, so I think I wanted to let others behind the curtain to experience what I did with him.

Tell me a bit about your personal history with Chuck.

I met Chuck in 1997 and over the next few years our paths crossed in the local Cleveland music scene. I interviewed him on an internet radio station I worked for, I booked his band, VUA, for a promotions website I helped create, and I lent the guy money here and there. He and I developed a level of comfort and trust and limits to where we started working, like I said, on a book, but also we hung out, went to the occasional concert, and I helped him with certain aspects of VUA as they worked toward releasing their debut.

He recorded an album with my band, Indoria, called You’ll Never Make the Six (InfiniteHive records), which was our first attempt at him writing stripped down, acoustic tunes. He ended up singing vocals on all of the songs (sometimes lead, sometimes little bits in the background), and writing and performing one of the songs on vocals and guitar.

The book is a bit different than your standard rocker bio, given your direct involvement in Chuck’s life. Explain to us how this gives the book a different edge than most.

At the end, and really for the last 20 years of Chuck’s life, I was there with first-hand knowledge of what was going on. I was with him when he agreed to put out the VUA album, I visited when he was in rehab, I drove him to AA meetings, I sat in support of him in court, I played 160 shows onstage with him, we recorded an album together, we bickered about anything and everything.I think it is a bit different because it doesn’t follow the typical rock narrative we see in books and movies. This isn’t The Dirt and we were not Mötley Crüe. We didn’t meet until after he had been in bands and toured and found drugs and broke his back in a car accident. We didn’t have any big success; we didn’t party and crash expensive cars. We were a couple blue-collar nobodies just trying to reach an audience and having no idea how to do it.

Was the book difficult for you to write, given how close you were with Chuck?

I’m grateful to my wife for giving me so much space after Chuck passed. She allowed me to shut everything down and concentrate on telling this story. If I had waited… If I tried to write this book now, I couldn’t. I put the words to paper when it was fresh, raw and when I was too in shock to process my grief and to let it overwhelm me.

You talk in the book about how you and Chuck talked about writing a book about him while he was alive but he was concerned about having a good ending. How did you approach this book with that knowledge, and knowing that the ending was his death?

I faced it head on and started with his death. He had a lot of plans going forward, a full tour in 2018, a new solo album, reuniting VUA, and more, so I tried to show how he had gotten to the point of touring with me, and then went in depth on our struggles and small victories on the road, including two reunion shows with Faith No More, a seven-songs-in-two-and-a-half-days recording session with Matt Wallace (Faith No More, The Replacements, Maroon 5), getting arrested, fighting addiction, and the joys of being stuck in a car with each other for endless miles. There was no happy ending possible, so I tried to tell it like it was, warts and all.

One comment Chuck makes in the book is pretty amazing, where he said he didn’t want to tell the crowd at a particular show that it was being recorded for a live release because then their reaction wouldn’t be genuine. From the outside looking in, that seems to sum up Chuck. What does a statement like that say about him?

There is no way to properly communicate how deep-rooted his anxiety was when he stepped onstage. Chuck believed with every breath that he wasn’t good enough. That people wouldn’t like his songs or his voice or his guitar playing or even him as a person. He found it impossible to face this fear without the help of drugs or alcohol, although he tried several times, and yet he always desired honesty and openness when presenting his art. He didn’t want to build a false buzz about what he was doing. He didn’t want people to enjoy his songs or performances simply because of his past or because the crowd might hear themselves on a recording. He wanted to share his inner thoughts and for them to stand on their own.He cautioned me against telling the crowd to move up to the stage, or to sing along, or to clap louder. He just wanted things to feel natural. He wanted the crowd to dislike his stuff if they didn’t enjoy it. He wanted them to stay quiet if they weren’t entertained. He wanted to listen to the crowd’s banter as we played, and he did. He remembered what people said—even when we got loud and noisy, he was listening.

You say in the book that usually Chuck did great for smaller crowds but for larger crowds or when press showed up, he “wilted.” Why do you think that is?

He told me he felt like an outsider at all times. Even as a teenager when he went to punk shows and the crowd was full of misfits who bonded together over being outsiders, he still felt out of place. It all goes back to his self-doubt. It consumed him. It caused him to shoot himself in the foot, over and over, typically at the worst times. He was always waiting for someone to turn off our sound and tell him he was a fraud. He expected each night the crowd would boo us off the stage and say he wasn’t good enough. It’s all a projection of his inner demons. He was put up for adoption as a baby and he never got clarity as to why, and I think that played into it as well. He was booted from Faith No More as things were really kicking up and that played into it as well. The first couple of years after FNM he described (and others have told me) as dark days. He was depressed and broke and directionless and he turned to drugs to cope. He reformed his band Haircuts That Kill for a time, but he was unable to drive them out of their practice spot and onto the stage or into a studio. Then he was asked to join Bad Brains and had a couple productive years touring and recording, but before their album with him was released, they got an offer to reunite with their original singer, HR. Chuck found himself ousted from another band just as a new contract was bringing in money and tour support. He had played the good soldier, maybe for the first time in his life, yet the result turned out the same. He had no band. He had no support. He had self-doubt over his abilities.

Returning to L.A., Chuck started jamming with some friends who had a band started and they became Cement. They recorded an album, toured and gained some buzz. Then, after singing a small deal in the States and Europe, they recorded their second album with producer Bill Metoyer (Slayer, D.R.I., Sacred Reich). They embarked on a tour, but a van accident derailed everything during the first week. Chuck broke his back in the accident and by the time the dust settled the album had stalled and the band had split. Once again, he found himself at square one.

To Chuck’s credit, he tried, again and again, to rebuild and restart, but found it harder and harder with less buzz in return. Even as a Chuck fan, I was unaware of what he was doing as this happened pre-internet, pre-music websites, pre-24-hour news cycle. His nerves and anxiety only grew as his neuroses seemed to confirm their truth.

Now, having said all of that, the stories I have heard from his earliest days seem to confirm that even back then, as he toured with Faith No More, these same patterns presented themselves. There is no lack of proof, such as the disastrous release show for Introduce Yourself, which I read about in Adrian Harte’s Small Victories: The True Story of Faith No More.

He puffed out his chest onstage, was as bratty as they come, sang candidly about his fears and demons, maintained a loveable goofball image, and yet he never was able to face his issues, head on, during his life.

How do you want people to remember Chuck?

Chuck was so many things to so many people. I hope people remember Chuck for whatever he meant to them. He was a husband, a father, a son, a brother, a bandmate, a shoulder to cry on, a source of entertainment, a joker, a poet, a partier, a World War history buff and so much more.

He was poor his entire adult life, but since he has passed, I’ve been contacted by so many people around the world, mostly strangers, who have shared how he helped them. He listened to anyone who wanted to talk. He consulted people who came looking for guidance to battle addictions, even as he struggled to fight his own. He had people move into his home when they had nowhere to go, he cooked for people, he took chances on people, and I don’t think he ever said no when someone needed a home for a stray pet.

Do yourself a favor—grab the two Faith No More records [that Chuck sings on], the Cement discs, the VUA CDs, and anything else he was involved with and give them a spin. Listen to his voice, his lyrics, his honesty, his fear, his passion and his pain. Remember Chuck by his music, for sure, but carry with you his humanity, his humor, his love for his family, his curiosity, his endless desire for mischief and the deep-rooted desire he had to connect with all of you and to feel accepted for who he was.