Much like Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut, Christian Death’s 1982 debut Only Theatre Of Pain starts with the ominous sound of bells. The similarities don’t end there. Much like Sabbath’s debut, Christian Death was created by young misfits who didn’t fit in any established music scene and decided to create their own universe. Much like Sabbath’s debut, Christian Death’s eerie look was a lure to young listeners. Much like Sabbath’s debut, Only Theatre Of Pain was helmed by a once-in-a-generation guitarist who invented an entire approach and style. And, much like Sabbath’s debut, Only Theatre Of Pain broke barriers and boundaries and led to the creation of a new genre of music.

Christian Death was birthed in the early ’80s Southern California hardcore scene in the unlikely locale of Pomona, California, a community known for its citrus trees and private college. While the early ’80s OC hardcore scene preached rebellion, it in some ways mirrored the values of conventional society, particularly its overt masculinity. Roger Painter — who took the name Rozz Williams from a gravestone — changed that. Williams, then in his late teens, upended and subverted the punk scene with his memorable demeanor and appearance long before he played a show or recorded an album. He soon met James McGearty and George Belanger, young punk roadies and aspiring musicians, and the earliest lineup of Christian Death came together.

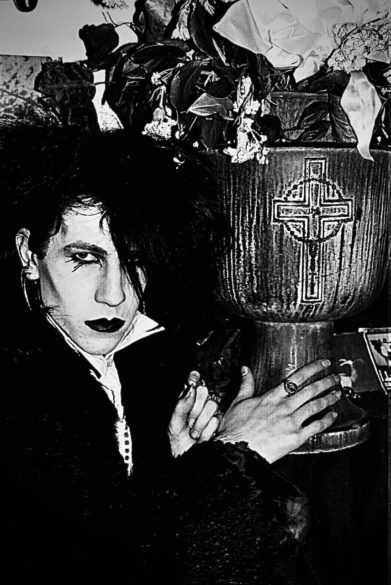

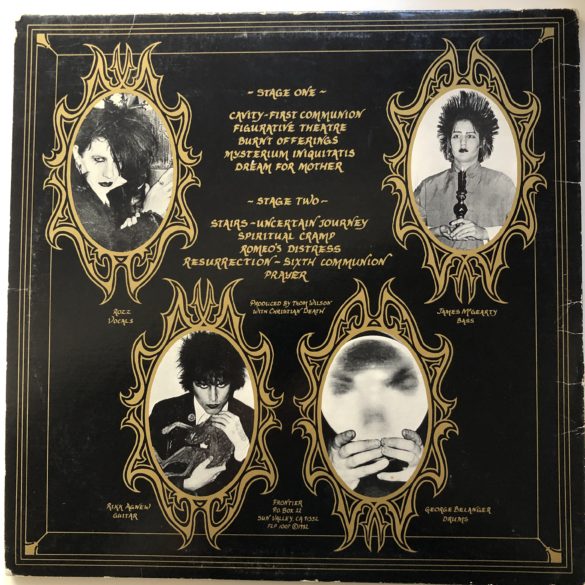

Christian Death became a fully-realized band when noted hardcore guitarist Rikk Agnew joined after he was kicked out of The Adolescents. Agnew was a few years older than his bandmates but far more experienced. Within months, Christian Death recorded their debut. While metal pioneers Venom seeded a musical revolution with blasphemy and testosterone, Christian Death’s different but no less subtle revolution borrowed from subversive authors like Bataille and DeSade, S&M culture and gothic horror. Christian Death’s blasphemy was less overt angst and more psychosexual boundary-pushing. Little surprise that there are talks of one studio session being haunted (more on that below). Christian Death’s image and reputation were helped by punk chronicler Edward Colver’s photography, including candid images shot in local cemeteries and even childhood homes. Those images were recently collected in Colver’s coffee table book, released in conjunction with Only Theatre’s 40th anniversary.

Only Theatre Of Pain is both a product of the early ’80s and an album beyond time. The songs are as fresh and vital as when they were first heard four decades ago and the aesthetic shows up in band photos and lyrics on a weekly basis. The list of bands influenced by this record is legion but would include Celtic Frost, In Solitude, Tribulation, Atriarch, Tombs and emerging black metal artists like Lamp Of Murmuur. The second wave of black metal’s look and approach would not exist without Rozz Williams and Only Theatre Of Pain. Local goth nights in cities across the United States might not exist, either.

Sadly, Williams took his own life in 1998. He was just 34. This record is his greatest gift, the work of an artist advanced beyond his years, an artist who flourished in his teens and died young like the Romantic poets (See: Byron, George Gordon). Decibel talked to all the living members of the Only Theatre lineup and other music industry vets about the making of this timeless classic and its legacy.

1. Act One Is The End

Only Theatre Of Pain is 40 years old. Is that unbelievable?

RIKK AGNEW (guitarist): Kind of. It does seem like a long, long time ago.

JAMES McGEARTY (bass): It’s mind-blowing. It’s hard to believe it’s been 40 years, and it doesn’t seem like it’s been that long in some respects. But it was a long time ago.

GEORGE BELANGER (drums): Absolutely.

EDWARD COLVER (photographer): Everything I worked on is 40 years old now (laughs). I’d worked on 80 punk records by the end of 1983.

Are you surprised that this album has endured? At this point, Only Theatre has been around longer than Rozz was.

AGNEW: No! I don’t fuck around when I write and come up with ideas. I write for staying power. I don’t stop when I write unless I’m content with it because I’m not wasting my fucking time. I want to give people an experience. When I let a song go, it has to stand the test of time, including Rikk time. I give everyone a thumbs up for effort when they write a song. It takes cajones, and a lot of people can’t do it.

McGEARTY: It’s a testament to something so quick, so organic. We all came at it at this certain point in our lives. Rozz had a vision of what he was trying to do, and when Rikk joined the band, it changed the trajectory. For a moment, it all just clicked.

LISA FANCHER (Owner, Frontier Records): When it came out people were so mad and offended by it. So, no, I didn’t think people would be buying it 40 years later or calling it one of the best albums of all time. It didn’t sell well compared to the punk rock stuff and some people thought Rikk was losing his mind (laughs).

Where were you in your life when Christian Death started? How did you get into Rozz’s orbit?

AGNEW: I was booted out of The Adolescents for the first out of four times (laughs). It also happens to Casey [Royer] all the time. They always end up kicking us out. The Adolescents were doing great, and I saw so much potential. We talked about U.S. tours with Black Flag or Dead Kennedys, and I was excited. We were called in for a meeting about the tour. I got there on time. I was waiting for over an hour. They finally get there, and it’s brought to my attention that it wasn’t about the tour but about kicking me out.

McGEARTY: I was part of the skate-punk movement. All of our friends were skate punks and grew up in punk rock. If you were punk, it didn’t matter what part of L.A. you were from. People wanted to talk to you because there weren’t many of us. I’d seen Rozz around, mainly in L.A. and other areas. A guy who lived in my city named Wallace would tell me about Rozz. Rozz always traveled in a group of three people. So I’d see him around but never talked to him.

The Decadents and The Stepmothers were playing one night. George and I were roadies for The Stepmothers, and Rozz was a roadie for The Decadents. We started talking about music. We exchanged numbers, and that was it.

BELANGER: I was a kid who loved to play drums when I met Rozz (Roger when we first met). We had a conversation and shared the same interests musically, and it seemed like a good idea.

COLVER: I met Rozz through Rikk and some local bands. I spent a lot of time in Fullerton and Costa Mesa hanging out with the guys in D.I., The Adolescents, and Social Distortion. So I was in the area a lot and had known Rikk since 1980. The Orange County hardcore family tree is crazy. Everyone had been in at least ten bands. Rozz was an interesting, smart, funny character. At the same time, Christian Death was a serious, amazing band. There was nothing frivolous about their music.

How did you start playing music with Rozz?

AGNEW: We’d played with Christian Death maybe a month before I was kicked out of The Adolescents. We were headlining in Pomona with another band called Bad Religion. We wanted to get them on a show (laughs). Christian Death was the opener. I thought they’d be a fucked up thrash band or punk.

They set up these lilies all around the edge of the stage. There were people dressed like it was a funeral, playing this funeral music. I thought it was weird but kind of cool. Rozz stood there with a microphone and almost mumbled the first song, “Burnt Offerings.” James played the bass line, the drums came in, and there were no guitars in that part of the song. I thought it was curious. They played four or five more songs like “Spiritual Cramp” and “Figurative Theatre.” They played the songs slowly, and the guitar player just followed the bass notes. They just looked spooky.

McGEARTY: Rozz wasn’t a talkative person. It was even difficult for people around him to get to know him. I just had a chance to meet him. I didn’t even know how to play bass, although I had a musical background. I was musical but didn’t play bass. I was given a bass by people who played in The Stepmothers. When I called him, I told him I played bass, and he invited me to a house in Claremont to practice. I brought my bass with me but could hardly play. I played a few notes, and he said, “you’re in.” That’s how it started. When I was walking out, he asked if I happened to know a drummer. When I got home, I called George and told him. We both met with Rozz and the original guitarist, and that was it.

Would you say that this record exists because Rikk joined the band?

AGNEW: The first time I heard them, I was filling in blanks. I thought so much could be done with the songs and that this was the band I was looking for. I listened to the songs thinking they could be better with new stuff on top of it. I was thinking about Siouxsie [and the Banshees], PiL [Public Image Ltd], Swans and even U2. After the show, George and James came out front, and we talked for quite a while.

I thought we could make the ultimate spooky, scary record. It’s something I always wanted to do. Did you ever see a movie called Phantom Of The Paradise? I’d thought about making a band like this since high school. There’s a part where this band comes out almost dressed like death rockers in full-on goth makeup. I wanted a band where the band members look like Frankenstein and Dracula. When I saw and heard Christian Death, I thought, “this is the band I’ve been thinking of all my life!”

McGEARTY: Rikk joining the band enabled a musical direction for the whole album. It was the special ingredient that allowed the music to develop. We played a show with The Adolescents at this boxing gym. Rikk saw all the people in front of the stage. He thought to himself that he wanted to be in this band. So, he got in touch with George. George called me and said: “you aren’t going to believe this, but Rikk Agnew wants to be in a band with us.” We played Cuckoo’s Nest and the Whisky, and soon after, we were signed. Much of that had to Rikk’s reputation with The Adolescents. We quickly had offers from Posh Boy and Frontier.

BELANGER: Rikk looked at our foundation. He knew James and I were into jamming and building songs together — how the bulk of the songs came about.

COLVER: I think they all contributed. George contributed a lot of interesting, weird percussion. Rikk is a genius guitar player, and James is a great bassist. I don’t think it was lopsided.

FANCHER: Absolutely. It might have been a good record but I’m not sure if I would put it out without Rikk. Rozz’s lyrics are brilliant but Rikk’s arrangements added so much. He was the most ill-behaved musician of all time but he took the arrangements seriously. Without Rikk’s musical touch, I don’t think it would be the same record.

ANDREW CORSON: (Fathoming Heavy podcast/former music writer): Only Theatre Of Pain could not have happened without Rozz’s partnership with Rikk. Rozz had his thing, and Rikk had his thing, but the impact of those things coming together was far more powerful than anything either would do alone. Rozz seemed to present his purest self and most profound insights through these symbiotic partnerships.

Once you were in the band, did you spend much time practicing?

McGEARTY: Rozz had written a lot of bass lines and would teach me things. We started doing punk, but Rozz said we needed to think of things in different terms, as scary and dark. That changed everything about the music and where we were headed. I learned through doing small progressions and rehearsing and writing songs.

Rozz is universally presented as this dark, tortured soul. I have to imagine that you saw different sides during all your time with him.

AGNEW: When I first met him in Pomona, he was primping in the mirror. He had the makeup on, and his hair was poof-ed out with a white stripe through it. I talked to him the most in the early days of the band. But I didn’t see him at rehearsals on a steady basis. It was always me, George and James at James’s house.

Rozz would just come in and wouldn’t talk. It was almost Andy Warhol-ish when I think about it. One time we came up with some new songs, and he had lyrics to try out. He had a book with lyrics and would look down at the book. We’d do the song, and he’d read the words out of the book. And that was it. That was how he did it. He was always quiet and would hang with his little posse of people. He was nonsocial.

McGEARTY: It wasn’t an act. It was who he was. He was a quiet, mysterious person and interesting and deep. He would get into these dark, depressed moods, and there was no approaching him. There would be a wall up, and you couldn’t talk to him or help him through whatever was bothering him. There were also a lot of drugs at play that added to the situation.

BELANGER: Rozz could be funny. James and I were hyper kids and mischievous personalities.

2. Figurative Theater

What do you remember about recording Only Theatre Of Pain?

AGNEW: We were always on acid (laughs). It was a lot of fun, and we had the run of the place. There were no rules about how to sound. We knew what we wanted. That’s what was good about working with Thom Wilson, who also did The Adolescents, my solo album and Dead Kennedys’ Plastic Surgery Disasters. He always made cool suggestions. When it came to Only Theatre Of Pain, we had all sorts of ideas. I’d go, well, there is a grand piano. I’ve always loved John Cage, and I tried to do John Cage stuff on the piano. We did whatever the acid told us to do (laughs).

McGEARTY: One of the moments that stands out is when we loaded in the equipment. Rikk requested all of these different instruments he envisioned playing on the record from Lisa [Fancher, owner of Frontier Records]. There were timpanis and tubular bells and things like that. Sunset Gower had one of those elevators that came up the street. I remember looking at all this stuff in the elevator, wondering what the fuck we were going to do with this equipment.

Recording a record in a studio with a producer like Thom wasn’t inexpensive in those days. It was exciting and mind-blowing. George and I went in and tracked the rhythm section. There wasn’t time to do a lot of takes or cut and paste as you would today. At one point, Thom plugged in a DI box with a fretless bass; it just sonically shaped everything that happened.

BELANGER: Recording was fast until the point Rozz did his vocals. There was an issue with the studio, which is a shame because his first set of vocals was amazing (more on that below). The problem with the studio was a bad deal. Rozz went dark on the second run-through.

COLVER: I saw them play the songs live, and it sounded amazing in the studio. One night I was at Sunset Gower while they recorded. Afterward, they grabbed their equipment and walked up for a show at the Cathay De Grande when they finished. It was the same night Rozz tore pages out of the Bible.

FANCHER: We spent three or four days making the record. It was a big, weird circus. Frank Agnew and Steve Soto from The Adolescents were there just because they were bored. Rozz had a pile of hangers-on. Rikk wanted tubular bells and I rented them. It was expensive. Rikk would also show up late or after drinking and wouldn’t want to play. The haunting is a good story and I have no explanation. I can’t in any way say the studio wasn’t haunted but we finally got the vocals.

Can you tell me more about the lost vocal take?

AGNEW: I hate going back to that evening because it still freaks me out. We’d done all the instruments, and Rozz went through and did every song from beginning to end. They were the most amazing sounding vocals. We didn’t know where they were coming from. The original sound was more like the vocals he did later — like Bowie. We thought the album was going to kill. He got done, and we asked him to come and hear it.

Rozz’s boyfriend came into the room with a weird look, and he said Rozz was in a bad way. He was freaking out. All of a sudden, it was like we could see psychedelic animated flames. It all happened so fast. Thom queued up [the recording] for Rozz to hear, then said there were no vocal tracks. Thom kept checking, and his face was like a ghost. He said he’d never had this happen in 22 years. Suddenly, the light in the studio got bright, and the temperature dropped about 30 degrees. You could see your breath. The feeling of evil was very strong. We all got up and ran out of the fucking studio. Rozz went back a few days later, and I don’t think it sounded as good. But there was no telling him. Then it became this popular voice, and kids know Rozz’s voice that way.

McGEARTY: That night was tough to grasp. Rikk and I were in another solar system. The guys in the studio told us that the best way to come down [from LSD] was to drink more orange juice (Ed: citrus is thought to enhance psychedelics). It distorted my entire perception of reality. The vocals Rozz first tracked sounded otherworldly. If you listen to the voice on the record, it’s nothing like what everyone heard that night. It was so different. That night it felt like something was conjured that was beyond words.

Could part of that perception be the psychedelics?

McGEARTY: Absolutely. That’s an indelible part of the experience. But everyone there had a similar experience. It impacted me to the core of who I am to this day. It was intense and scary, and super real.

What was your reaction to hearing the record?

AGNEW: Besides the changed vocals, which I got used to, I liked it.

McGEARTY: I was excited. It’s strange to hear yourself on a record for the first time. Having this album didn’t change a lot of what was going on. We were still playing gigs for $50. Some of the early reviews were very unflattering. We didn’t think we had recorded or delivered a landmark record. It was still an incredible feat just to have a record done.

BELANGER: Thom Wilson gave me a tape of the final mix. When I received the test pressing, I listened to it and said alright. I guess it’s done then.

FANCHER: I loved it. I got some bad reaction to Rozz’s vocals. Some people even asked for copies without vocals. I thought it was a masterpiece.

What did the bad reviews say?

AGNEW: I ignore reviews. Opinions are like assholes. Everyone has one, and they stink.

McGEARTY: I may still have some of them. They were saying things like they didn’t realize Rozz was a man. Or they said it sounded like Rozz gargled with bleach. A lot of things that happened for this record and the following that happened over time occurred after this lineup broke up. We gained a little more popularity, but soon, George and then Rikk left. The lineup of Only Theatre Of Pain only lasted maybe a year at most.

And yet this is one of the masterpieces of American underground music.

McGEARTY: It was a cataclysmic event when the four of us got together and wrote these songs, recorded them and broke up shortly after.

3. An Illusion With Hand and Pen

When in your life did it occur to you that this record never went away and had become this legend?

McGEARTY: To get myself where I could move forward in life, I had to distance myself from anything involving music or playing music or even listening to anything from that period. I learned that people were interested around the 25-year mark and understood then that this record meant a lot to people.

How did you discover Only Theatre Of Pain?

CORSON: My first listen was when I was 15, in 1987, when an older friend played a cassette copy over a crappy boombox on the bleachers in our high school gym. Growing up in the Bay Area, it was nearly all thrash metal all the time, but I had a soft spot for slightly spookier stuff and was super into 45 Grave, Samhain and The Cramps. Still, it was two years until I finally bought a copy, and everything changed.

AESOP DEKKER (Ludicra/ex-Agalloch): I first became aware of Christian Death via the book Hardcore California by Peter Belsito and Bob Davis. It was Colver’s evocative photos of Rozz and Shron performing live [that grabbed my attention]. Shron is crucifying a dead cat, and there are lots of bones and bells adorning Rozz. I was 14, and this instantly became one of my “must hear” bands. I snatched up a copy from Open Books & Records in Miami and spent the long bus ride home examining the jacket, the band photos on the back (another dead cat), and the hand-written lyric sheets. The lyrics, holy shit! Rich with nasty imagery, naughty words, taboo. Only Theatre Of Pain impacted me before I ever heard a note.

MIKE HILL (Tombs): I was a big fan of Propaganda magazine. They had great coverage on industrial and goth music. I remember seeing the Christian Death name in print back in the ’80s. I bought Only Theatre Of Pain without knowing anything about Rozz.

BOBBY FERRY (16): In 1983 I was record shopping with the sole purpose of buying Suicidal Tendencies and Fear when I saw Only Theatre of Pain with Rozz and Rikk holding a real dead cat (on the back cover). I said to myself “this must be great” and it was. Growing up in Southern California in the ’80s their influence was hard to ignore.

SERA TIMMS (Black Mare): I was chatting with someone at an Atriarch show and they mentioned Christian Death. They were shocked that I didn’t know about them. Shortly after I was gifted the vinyl and began the “psychotic repeat” cycle that all my favorite albums and songs go through. At the time I was listening to mostly ’80s and neo ’80s goth, new wave and lo-fi melodic black metal. I used to love to drink red wine and listen to this album in my little woodsy house in Mount Washington. At the time I felt like an outsider in the status quo world, and musically found myself somewhere between the metal and goth “boxes.” This album was another freak, but a perfect freak.

What was your reaction?

CORSON: It was all the things…dark and heavy and oppressive, but it was something else, too. It felt like a single cohesive piece of work, operatic, almost like Reign In Blood. It had the flow and depth of a ritual, filled with super weird and symbolic imagery that appealed to and unlocked something in my 17-year-old psyche. The album was uncomfortable and subversive but also inviting. I got some of it right away, the Bowie and Alice Cooper and punk rock bits, and later used it as a springboard to explore Artaud and Baudelaire and Blake, all of whom were new to me but cast massive shadows over the record and Rozz’s life. Ultimately, it was a catalyst for much of my own psychological and spiritual growth and exploration.

HILL: It wasn’t like anything I had heard before. The deep sense of nihilism and anti-religion sentiments resonated with me. There was a feeling of betrayal with Christianity, especially in the lyrics of “Spiritual Cramp” — my favorite song on the record.

TIMMS: There is something so strange about Rozz’s voice. He sings in this sort of swaggering, chopped, shrill, punk rock style that technically is something that would annoy me but it is somehow infinitely graceful in its storm of contempt. I still can’t logically make sense of why I love it so much, but I do think this is connected to the rare gift of an artist who creates the perfect world to house their voice. The guitar on this album is just so free, so atmospheric, and so weird. I always liken music to church, as the purest intangible mystical experience I have had is with music. This album was sort of like finding that church full of ghosts and with graffiti all over the walls.

What influence has Only Theatre had on metal?

DEKKER: I think Christian Death’s influence on metal is an aesthetic one. It’s no coincidence that my earliest interest in the band was based on a visual element, but the lyrics tie together a vivid and inventive world that has a lot of overlapping themes with metal, particularly black metal. Rozz had a gift for prose that few since have matched.

HILL: If you’re creating metal with that darker edge, you are most likely a Christian Death fan. The track “Spiritual Cramp” was a big influence with the antichristian lyrics, punk riffs and languid vocal style.

FERRY: Rozz set the standard for the deathrock look; even metal and hardcore punk people back then were into it. The chord progressions had that waltz-type haunted feel and most of the songs are slow, heavy and doomy with over-the-top fuzzy guitar. Even the gnarliest metal dudes were like “that shit is heavy, dude.”

Were you in touch with Rozz when he took his own life? How did you hear about it?

AGNEW: I wasn’t around during that time. They were in Europe a lot, and we didn’t hang out. I was doing other stuff. [When I heard] I lived in a basement in this place called the Arts Colony in Santa Ana. I think I heard from a friend who got a call from George but I wasn’t surprised. I thought it might happen some time because I knew he dabbled a lot in drugs and got really into drinking.

McGEARTY: He and I lost touch after he went on tour with Rikk and Casey Chaos. Before he left on that tour was the last time we spoke. I was shocked that it happened. People thought he might overdose, but hearing how he ended his life was sad. He was such an amazing, interesting talent and an incredible artist across mediums. Unfortunately, the world couldn’t appreciate what was there back then. I always wished the original lineup could make another record. But it didn’t work out that way.

BELANGER: I wasn’t in contact with Rozz when he took his life. I don’t remember who called me. I don’t like talking about that.

CORSON: I saw Rozz perform nine times, met him several times, and formally interviewed him twice. I was starstruck the entire time I interviewed him and wish I had the opportunity to do it again. Both interviews were in early 1996 via phone, and I could hear Sabbath’s Master of Reality in the background during the first call. We talked a lot about KISS, who he’s on record as hating but admitted to me that he loved.

Do you ever look back and see a sort of innocence to the period, especially in the band photographs?

McGEARTY: I just turned 18 when we recorded this album. It’s pretty profound to think we were able to create something so simple yet so rhythmic and mind-blowing. I don’t think anyone could imagine it made such an impact. I still think what Rozz was saying was real and sincere. When you hear many artists try to fit in a genre, it seems contrived — like they are trying to be something. He wasn’t trying; he just was. The album is interesting and timeless to this day.

COLVER: I had access to them and managed to get photos that got used a lot and became recognizable. People overuse the word iconic, but it seems like many of the photos have become iconic. In all my punk rock stuff, everyone I was photographing was a kid or in their early 20s at the most.

4. Satan Be Gone

Rozz lived how he wanted long before it was safe to make those choices public. Is part of his legacy that courage?

AGNEW: I have a hard time answering questions like that because I don’t get the homophobia. I never understood it. There was a reason we got along so well: None of us ever thought about stuff like that or gave a shit. If anything, I thought it was punk rock to be in people’s faces and shock them and be who you want to be. I never thought twice about it.

McGEARTY: He was way ahead of his time as an artist and person.

COLVER: Possibly. I think that community adopted him. He wasn’t any kind of advocate or activist as I can recall.

FANCHER: I didn’t know Rozz well because he didn’t speak much. He split a few months after the record came out. But he was so different. When he went to school he would wear anything he wanted and I’m sure he was horribly bullied. It just made him bold. He never tried to be normal, fit in, or sell out. Rozz fans are absolutely rabid because they feel like he got them.

DEKKER: He was to ’80s kids what Bowie was to ’70s kids, like this enigma that says “hey you’re weird, and it’s OK.” As I get older, I don’t see him as this wild, free-spirited libertine, considering how his sun set. Having somewhat grown-up myself, I see someone struggling and wounded; it kind of casts Only Theatre Of Pain [and the other records] in a new light.

Why does Only Theatre Of Pain continue to find new generations of listeners?

McGEARTY: It was what Rozz was saying. The words, poetry and lyrics came from a genuine place inside him.

FANCHER: It doesn’t feel stuck in time. It’s well recorded and has no trendy things. And the subject matter could still bother your parents.

DEKKER: The simple answer is because it’s a brilliant work, great songs (don’t even get me started on the genius that is Rikk Agnew.) Maybe the long-form is because of its reputation as a genre-defining classic? Every kid that discovers black metal will buy A Blaze in the Northern Sky. But why does something get to enjoy that sort of status? Sometimes it’s simply a matter of time and place; in other instances, it’s just a solid bit of art.

HILL: Only Theatre Of Pain is as important as Black Flag’s Damaged, any Minor Threat record, or any other prominent records from that era. The “goth” style was primarily European, with bands like Bauhaus and The Damned leading the charge. T.S.O.L., Samhain and Christian Death put the U.S. on the map with that style.

TIMMS: Original works of art are like seeds that never die. Art which flows freely from the muses through the artist into the creation is rare these days. Art and music have always helped people to better understand their own human experience and angst. And people who actually want to be nourished by art versus entertained by art will dig through the musical detritus until they find the pure seed. The seeds are always copied and cultivated into new forms, but they can’t truly be duplicated. This is the intangible magnetic mystery of Only Theatre Of Pain.

What is Only Theatre Of Pain’s legacy?

AGNEW: It established a whole new genre of music. We were not the first ones, but we were the most serious and scariest. Forty years later, the songs still have that validity and still have an effect. We must have been doing something right.

McGEARTY: The songwriting and how it came together was powerful and a unique moment in time. It documented a time when four kids lashed out at established religion. The messages and music we created still mean things and move people in ways we could never have anticipated. The record is still viable after all of these years. To be considered one of the classics of deathrock and goth memorializes what a visionary Rozz was. You can play music your whole life and not make a difference and look at what this record did.

COLVER: It was groundbreaking and became influential. It’s a milestone record that wasn’t appreciated at all at the time.

FANCHER: It’s one of the top goth records of all time. It created the genre and the look and it’s indispensable to anyone who is interested in the dark side of music, especially because of the awesome musicianship. It’s one of the best sellers I have and new people discover it all the time.

CORSON: It’s weird to think these guys made this record when they were teenagers or barely out of their teenage years, but that might be why it still feels so fresh. It’s honest and unfiltered and cringeworthy at times, which is why it still resonates with me. When I feel like I need a place to land and collect myself, I always go back to that record. It’s like hitting reset and reminds me of some essential parts of myself and inspires me to get back there. Could they have done this again or made something even better? Who knows. Part of its greatness is its singularity. It’s a one-and-done, a mic drop and leaves an untainted legacy. There’s a bit of poetry to that.

FERRY: There were other bands at the time, but Christian Death created a masterpiece that nailed it with the image and the music. Only Theatre is great from start to finish. They were the originators of deathrock, which is much different than goth — grittier, darker, raw. It’s always been a seminal record to me and my circle of friends.