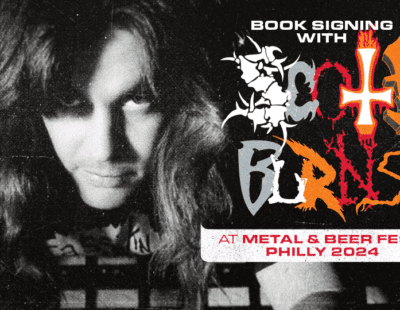

The metal writer Aleksey Evdokimov released the first volume of his Doom Lexicanum anthology back in 2017, devoting most of its 300+ pages to epic/true doom. Now, he’s back with the death/doom-focused sequel, Doom Lexicanum II. It’s a similarly exhaustive tome, featuring 324 pages of band biographies and exclusive interviews, and it sees Ekdokimov teaming up once again with Dayal Patterson’s Cult Never Dies imprint. Evdokimov’s knowledge of his subject matter is encyclopedic, and even if you think of yourself as a preeminent death/doom scholar, you’re likely to find a killer band that you’ve never heard before in these pages.

The book’s expansive interview section would make it a worthy volume on its own. Evdokimov gets Paradise Lost’s Gregor Mackintosh, Peaceville Records’ Paul “Hammy” Halmshaw, Academy Studios’ Robert “Mags” Magoolagan, and Aaron Stainthorpe and Martin Powell from My Dying Bride to talk at length about the late ’80s and early ’90s rise of the death/doom genre. Excerpted below is a portion of the interview with Stainthorpe, wherein the singer talks about the formation of My Dying Bride and the making of their legendary first demo, Towards the Sinister.

In Hammy’s Peaceville Life book he mentions the cult pub Frog & Toad an awful lot. Was that a part of your life, and was it part of the process of creating My Dying Bride?

Yeah, definitely. The Frog & Toad was actually a nightclub rather than a pub, it wasn’t open during the week, it only opened on Friday evenings and Saturday evenings – it didn’t even open until about 8 or 9 o’clock at night. I can’t remember where I heard about the Frog & Toad at first, but word got around that there was this really great club opened in Bradford that played rock music – but not just rock music, it would play extreme rock music, like your Slayers, and your Metallicas, and everything like that, and we thought, ‘Well, let’s go along and say hello shall we?’

So we went there – that’s where Paradise Lost formed and My Dying Bride and, well, probably a million other Northern-based bands, because people came to the Frog & Toad from all over the north, you’d get loads and loads of people turning up there. It was just a wonderful place to go to, you met friends for life there. It was a big place – upstairs was more your sort of Pink Floyd, traditional-type rock music, that’s where the slightly older generation went for their chillouts, but downstairs it was extreme music ‘til about 11, then it went on to your Bon Jovis etc etc. And that’s where I was first exposed to the likes of Bathory and Celtic Frost and things like that, because I’d never heard of these bands before – you know, I thought Motörhead was extreme as you could get, and then when I went to the Frog & Toad my eyes were well and truly opened! That’s how I met Calvin [Robertshaw, guitars] and then me and Calvin bumped into Rick [Miah, drums] and Andy [Craighan, guitars] and just decided to form a band.

So was that almost accidental that you had the right personnel to do that, or did you have that idea before hooking up with everybody?

No, I didn’t actually think about joining a band, or forming a band, at all. Calvin was the guitar player and I was good friends with Calvin for a long time, and we met before My Dying Bride, but the one rehearsal we had, it was pretty good. And I’ll tell you what led me into it, because when you hear all these death metal bands you think, ‘Well, I don’t need to able to sing, I just need to be able to shout,’ and I thought: ‘I can shout, I’m perfectly capable of shouting,’ [laughs] so Calvin had to convince me to come along and do some shouting, so I did. And I really enjoyed it.

And then I started writing lyrics, because I think I’d never written lyrics before, but I thought, oh, you know, ‘I’ll put pen to paper’. I’ve always been into classic literature, so I thought instead of writing about what everyone else was writing about, I might put a classic bent on things and tap into some classic literature and maybe sing about that sort of thing – or even in the style of that genre – so we ended up being a doom/death band with classical overtones. It could have been a right mess, you know, we could have been ostracized by the doom market because we were too thrashy, the thrash market ‘cos we were too doomy, and the goths could have just said we were far too metal… I’ve always wanted to be slightly awkward, and a bit weird. I think that must be the Celtic Frost stuff – or even Hellhammer, back then – and I just thought, ‘Yeah, I don’t want to do run of the mill stuff, I want to do something that’s a little bit quirky’. So I used literature, and the weird name of the band, and the melancholy, and the fast and the slow, and the violins, and it all managed to come together in quite a tempting package.

Looking back in hindsight everything gets neatly pigeonholed, whereas at the time it was all just developing organically – did you even call yourselves ‘death-doom’ to begin with, or was that something applied to you later?

We sort of did, but, again, taking a leaf out of Celtic Frost’s book, we decided to call ourselves ‘avant-garde doom’, but I think because Calvin loved his thrash and death metal, he was always wanting the word thrash in there somewhere – or death – so along the various points of our career we have been classical doom/death, and I think thrash has been in there as well at some points. I don’t even try to pigeonhole us anymore, because I think people just think we’re a doom band, although I’ve never thought of My Dying Bride as a doom band, because, you know, you only have to play a couple of our more extreme metal songs and people go, ‘Wow, that’s not a doom band! Doom/death seems to work and it’s really journalists and fans I think who make up those phrases. To me it’s just My Dying Bride: we do what we do, and other people have to label us, and I’m fine with that. I don’t get all angry and narky because we’re being quoted as, say, more death than we are doom, it doesn’t bother me – it’s from the journalist’s perspective, I suppose. If you like the thrashy fast songs, you’ll probably call us more of a death metal band, although I don’t really think many people are going to do that! I mean when I read magazines and websites and people say doom metal is My Dying Bride I don’t go, ‘Well, we’re not just doom!’ I really don’t care, I’m not picky about it all. I’m happy to be in the magazines, that’s all [laughs].

So it didn’t really take you all that long to get the original demo done: Towards The Sinister came out in 1990, the same year you formed.

That’s an example of how well we gelled at the beginning, the four of us: Rick, Andy, myself and Calvin. We just hit it off straightaway – I’m slightly older, but we’re all roughly the same age, and we all liked roughly the same kind of music, and it just worked. That first rehearsal it was just like a lightbulb, we were all thinking, ‘This is working well, it’s working well!’ I think that rehearsal was probably about four hours, and we probably wrote two songs just in that rehearsal, and then worked on a couple more. I think we’d only been together maybe three or four months, and we decided, ‘Right let’s do a demo tape, that’s what bands do.’

We all had demo tapes of other bands at home: tape trading was a big thing. Thankfully, Calvin worked at a printers, so on the side of a job he was printing for Michelin tires there was just enough room to squeeze on a demo inlay thing. So I designed it all, and we put the lyrics on and everything – in color with lyrics, you know people were doing photocopied stuff back then without lyrics, ours had the full monty, so it was all thanks to Michelin [laughs]. And that obviously makes the demo tape stand out amongst the others because, I mean, if you were running a fanzine back then you must have got tons of demo tapes, and they all looked pretty similar.

We wanted to make a statement with the first thing we ever released, and I think we got a thousand copies, a thousand tapes done. I guess we must have sent out nearly 200 to all the magazines and the reviewers and everyone like that, free of charge, and then through feedback we managed to sell… well, we probably had 100 that we gave to friends and they’re probably sat in a drawer somewhere, but I reckon we sold 700, which was pretty good going for the day! Back then it was all cash within envelopes: we’d get Deutchmarks from Germany and Guilders from Holland, and it’s like, ‘Fucking hell, I’m going to have to go to the bank or whoever to convert all this shit!’ Kids in bands today don’t have this problem.

You obviously had confidence in what you were doing, given you went straight to studio even for the demo?

Oh yeah, we weren’t mucking around, we wanted to do it properly because when you do as much tape trading as we did, you can see the ones that have been recorded in someone’s garage, or in a bedroom or whatever, and you can see the ones where they’ve put a bit more money and time and effort into it and you say, ‘That’s the one we like, we like these guys,’ and we thought, ‘Right, we want it to be as clean and polished and as good as it can possibly be with the budget that we have.’ The budget was, of course, ‘How much money have you got in your piggy bank’, and that’s all we had. No-one was throwing money, we had no sponsors, it was all out of our own pocket and so, you know, we spent the money to make the money, as it were, and it paid off.

Pre-order Doom Lexicanum II from Cult Never Dies here.