Cathedral’s debut, Forest of Equilibrium, wasn’t any of what their labelmates (or the rest of underground metal for that matter) were doing in 1991. Certainly, there’s precedence in the drawn-out, long-form doom and gloom the Coventry-based quartet (plus stand-in drummer Mike Smail) purveyed unapologetically. The obvious rear-view mirror look-back posits Black Sabbath, Witchfinder General, Trouble, Candlemass, and a host of others having contributed to all that’s heavy starting in the hazy late ‘60s and rumbling straight through to the early ‘80s. That 20-year expanse is age-long, but the fruits of that labor and untethered invention were consumed obsessively by four young Brits — several of which were (in)famously in Napalm Death and Acid Reign — enamored by the slower end of the extreme music spectrum. Forest of Equilibrium was, to Lee Dorrian’s analysis, a ‘90s version of early ‘80s Trouble reared in a different era. The primary spirit was the same, but the inputs and the surrounding environment were unlike anything before it.

What most of us didn’t realize when we picked up Forest of Equilibrium on December 6, 1991 (in the U.S. anyway) was Cathedral’s morose, sedate musical posture was also influenced by a host of others, imbued subtlety, perhaps naively, but always intently. Cathedral, through songs like “Commiserating the Celebration,” “Ebony Tears,” “Serpent Eve,” and “A Funeral Request,” were educating inconspicuously. How else could fibers of Dead Can Dance, Comus, Swans, Captain Beyond, and a host of then-unknowns (to us) find their way into Cathedral’s laden fabric? I would argue that we (the third estate, so to speak) were unaware that Forest of Equilibrium was slow marching with such varied and storied diversity. It’s not like the nine-minute expanse that is “Reaching Happiness, Touching Pain” would’ve informed otherwise. But there were hints. The flute intro to “Picture of Beauty & Innocence,” as played by Helen Acreman, tricked us into Renn Faire delight. Alas, there was no rainy-day frolicking to be had. We were briefly unentombed from the tombstone-heavy procession in “Ebony Tears” by Gary ‘Gaz’ Jennings and Adam Lehan’s twin lead interplay. Perhaps that was wrested from NWOBHM legends (or those that pre-date such magnificent din), but hidden under poverty-stricken enterprise. And the creepy acoustic plucking against a surreal churn in “A Funeral Request” definitely didn’t originate in death metal’s then-shallow grave. Swans, yes. Repulsion, no.

There’s no forgetting Lee Dorrian’s moans, caterwauling, and groveling either. Throughout Forest of Equilibrium, Dorrian put on a masterclass display of something new. We didn’t really know what was happening during the unexpected groove of mid-album “hit” “Soul Sacrifice,” but we relished in it. The album continued to stretch boundaries as it pointed towards the end. “Equilibrium” and especially “Reaching Happiness, Touching Pain” are really something else, an unhurried barrage of torment, pain, and hunger. Forest of Equilibrium would also likely not be itself had it not been for Dave Patchett’s Bosch-informed multi-color cover. No metal album — under or above ground — had that cover. The fantastical world of the long-legged, sylphlike walker against a backdrop of surreal madness (sin) and stark forest was undeniably alluring in the most unorthodox way. That it was unique to Cathedral indicated under the booklet lay the very start of a genre invigorated.

It is with belated celebration and several souls sacrificed — mostly interviewees Lee Dorrian and Adam Lehan — that we, the denizens of Decibel, burn the candles brightly as Forest of Equilibrium turns three decades old. The lines in “Ebony Tears” describe our compulsory ritual thusly: “Together we have discovered the languid fatigue of love / Interrogated all our beauty we’ve turned each other inside out.”

Forest of Equilibrium is 30 years old. What are some of the thoughts that immediately come to mind?

Lee Dorrian: I didn’t even realize it was 30 years old until I started seeing it pop up on social media. For a start, it’s really weird that it was released in December. December is a strange month to release albums. Having done the label [Rise Above Records] for a number of years, releasing albums in December isn’t always the best idea. That’s one of the reasons why I was so caught off-guard by all this. I would’ve thought it was released in August [1991]. I think those are the reasons why it didn’t spring to mind immediately. But now that I think about it, when the band got together to when we recorded the album they were very exciting times, even if we were extremely poverty stricken. We didn’t think the world was against us, but we didn’t think the music we were doing was going to be taken too seriously by people. Most of us had been in bands before, and we thought that might’ve helped with recognition, in addition to being on the same label – the previous band I was in [Napalm Death] didn’t harm things for sure [Laughs] – but we didn’t really think people would consider what we were doing all that interesting. While we did have a springboard, what we were doing wasn’t really popular at the time I remember. We were coming at things from a completely different angle. Being broke, sounding like we did, and being who we were, I’m sure we never really thought about where it would go. I think the one thing about the album is that we weren’t nearly as accomplished [as musicians] then as we were on later albums. By the time we did The Ethereal Mirror, Gaz [Jennings] and Adam [Lehan] had become far better players, and I think that’s pretty obvious. There are hints to what they were capable of before on Forest of Equilibrium. Matched up, they were very different guitar players, with contrasting styles, but they complemented each other. We were so influenced by Trouble, though. I remember thinking that we were what Trouble were in 1982. They had come up with influences from the ‘70s. We had come up with influences from extreme music. I think that’s where the darker sound or more extreme vibe came from. There’s no way we could’ve approached doom metal from the same angle Trouble did. We were from a different era. In no way were we trying to reinvent doom metal. More this is what we were capable of at the time. So, we were still finding our way on Forest of Equilibrium. I will say, there’s many things about the album that are deliberate. We had a lot of time to think about the presentation, the packaging, the artwork — all of it! Even the fonts and font color were thought out in advance. I suspect we had nothing better to do. [Laughs] But when it became time to make the album, we were happy and yet keenly aware that it wouldn’t go much further. We thought it’d be a cult album, but never taken seriously. I think it’s been more revered as the years have gone by than it was at the time. That’s OK by me.

Adam Lehan: How old I am! [Laughs] It’s a strange thing. I can’t speak for the others, but I don’t think I would’ve imagined back then that I’d still be talking to people about this album in 2021.

Do you remember how the Earache deal happened?

Lee Dorrian: I remember we couldn’t get signed. [Laughs] We tried with a few labels. Hammy [Paul Halmshaw] at Peaceville wanted to sign us. Monte Conner at Roadrunner was interested, but then that all went quiet. I think Hellhound in Germany were interested. It was only when the demo got reviewed in CMJ magazine when we became a little bit like a hot topic. So, I hadn’t heard back from Roadrunner for quite some time, which is why I started talking to Earache. When Roadrunner heard that Earache wanted to sign us, they were all over us. I’d get a fax every day. [Laughs] They were really keen to sign us. But we felt just because some other label — Earache — wanted to sign us that wasn’t a good enough reason. Also, Roadrunner were mostly based in America, and that was, in a way, a bit alien to us. I know the main office was in Europe, but it was America that were interested. Anyway, it was obvious that [Earache founder] Dig [Pearson] wanted to sign us. He had worked with me before in Napalm. Plus, Earache, at the time, were outdoing all other labels with their releases. They had Morbid Angel, Godflesh, Carcass… all mega-huge. No label could compete with Earache in 1990 and 1991. Earache, to us, felt the most natural label to sign to. Our mates in other bands were also signed to Earache. It made sense, really. I think that’s also when Columbia started to sniff around as well. Actually, if I remember correctly, we were thinking about doing it ourselves [with Rise Above Records] for a brief period, but I had no interest in doing the band’s administration any more than I already was.

The booklet for the original press listed a litany of bands most people had never heard of. Bands like Gracious, Mellow Candle, Camel, Comus, etc. How did those bands inform Cathedral’s songwriting/sound while you worked with the framework set by Black Sabbath, St. Vitus, Pentagram, Trouble, et al.?

Lee Dorrian: Well, I had just begun to discover underground progressive albums from the early ‘70s myself. Gaz had been into a few of those bands. Griff [Mark Griffiths] was also into bands like Comus. He had worked in a record store, and had been exposed to all that stuff. When we got together, we realized we all liked those bands more than we realized, and suddenly looking for all that stuff became a bit of an obsession. We loved digging out the most obscure ‘70s bands. That’s still something that goes on to this very day. If I were to do that band list today, it’d look like phone directory. [Laughs] To us, metal had become redundant, boring. The aggressive death metal thing was too much — the macho thing. Guys in t-shirts and shorts with their arms folded looking mean was fucking lame. I had enough of all that, really. We wanted to look the other way, and we did. We wanted something more exciting. Of course, we were all massive Sabbath – especially the early years – fans and when we started looking back, we started to look into the question who they were playing with in 1970 and 1971. We wanted to know about those bands. The more we dug, the more we found. It became a whole new world. The thing with that is: we then realized how restrictive metal had become. Metal had become one-dimensional. But these ‘70s bands had a lot more freedom of expression. They didn’t care about boundaries. They could take the music anywhere. That’s where and when we started to venture down the path of more than one dimension of sound. Sure, Forest of Equilibrium is sort of one-dimensional, even though it had flavors of other things creeping into it, but it lead the way for us to think about music with fewer restrictions. We could be less inhibited by what we wanted to do. The ‘70s bands were a big influence in that way. The way we dressed was part of that, too. Very influenced by the ‘70s, with tight flares and stuff. I mean, I found the image of ‘70s rock bands quite cool, but our reasons to dress like that was that we had found metal too stale, too machismo. I remember, we’d tour and there’d be these jock-type guys standing in the middle of the front row with their middle fingers aimed right at me for the whole set. They were so pissed off about nothing. Like how dare I stop playing in a grind band-kind of thing. They didn’t want to hear this hippie music shit. I would go right back at them to say, “How dare you?! Who the fuck are you?! I’ll do whatever the hell I want!” I would say we were adventurous, and nobody could do anything about it. Back to your question, I still find immense enjoyment in listening to all this obscure music – especially the British stuff – from that era. It’s not just progressive rock or psychedelic music either. I’ve also grown to love British jazz. That’s been a revelation over the last 10 years. Players like Don Rendell, Joe Harriott, and Ian Carr. I would’ve never imagined myself listening to jazz when I was 16-17 that’s for sure. [Laughs] I’m not talking casually either.

Adam Lehan: Whenever I’m asked about this kind of thing it tends to imply that we sat around planning this and that, and that’s really not how I remember it. We were all really into the ’70s music, and also stuff like Dead Can Dance. I recall listening to some Gregorian chants on CD at home and the like… And I think it just made its way into what we were doing without necessarily being overly analyzed or planned. I could be wrong of course, but this is my memory of it. For instance, the intro “Picture of Beauty & Innocence,” I had no idea it would turn out like that. Gaz kept going back in and doing multiple overdubs and we were like, “Every time he goes back in it gets more ’70s!” [Laughs] We were enjoying ourselves, and our lives were pretty miserable at the time so…

Lee Dorrian: Yeah, this goes back to the early days of Cathedral. When we first started out, we had a guy on drums named Andy Baker, who was originally in Sacrilege and The Varukers before that. We didn’t really have songs at the time – just a couple of Gaz’s riffs. Griff was also on guitar then. So, we had his riffs, too. We didn’t have a bass player. Our first rehearsals were a waste of time. We got to know one another better, but nothing musical came out of those rehearsals. I remember, our rehearsal room was next to Black Sabbath’s and we’d just put our ears the wall listening to what they were doing instead of rehearsing. [Laughs] It took a few rehearsals to get what we were trying to aim for. Then, one day, Gaz comes up with “Mourning of a New Day” and “Ebony Tears.” See, we used to send each other cassettes of riffs and stuff. We weren’t all from Coventry. I had lived in Coventry, Gaz was living in Harrogate, and Griff lived in Liverpool. We were from all over by a long mile. I get this cassette with “Mourning of a New Day” and “Ebony Tears” out of nothing. When Adam joined just before – the day before, actually – we were going to record our first demo, we knew we had something. Gaz had met Adam at a record fair in Leeds. Obviously, they had both been in Acid Reign at different times. But luckily, Adam was into doom metal, especially Candlemass. OK, so Gaz is more into Black Sabbath, Witchfinder General, and Trouble-kind of doom fan. Adam was into the more gothic doom stuff. Right out of the gate, they were contrasting in influence and style, but somehow complemented each other. I remember the cassette that Adam had sent me of “Serpent Eve” and “A Funeral Request.” I was like, “Fucking hell!” It was just the guitar. He had blown my mind. I couldn’t wait to get those kinds of songs recorded. Gaz’s songs were chunky and heavy. Adam’s songs were classic sounding, a bit more epic. Both styles of music really complemented each other, even though they’re kind of like drudgery. [Laughs] We had a year to hammer it all out. The more rehearsals we had, the more interesting things got for us. We were adding songs to the pot. The production is quite murky and muddy, which suited the material, but I think we thought we were going to have a more aggressive-sounding album. The mastering on the first song, “Commiserating the Celebration,” is a bit fucked up. I don’t think it’s mastered properly. The rest of the album is, but not “Commiserating the Celebration.” Not sure how that happened, but people have gotten used to it over the years. There are other things on the album that I like, too. The samples, I think, added to the darkness or shades of darkness on the album. The slowed-down Tibetan monks at the end of “Serpent Eve,” for example. The music box at the end of “Equilibrium.” The flute at the intro was completely out of tune. The vocals on “Reaching Happiness, Touching Pain” are completely tormented.

Adam Lehan: Songwriting was kind of erratic as we all lived quite separately, so we’d send tapes to each other, back and forth, with ideas, etc. I do remember being at Gaz’s house when we structured “Serpent Eve” though. Basically, the first half written by me and the second half by Gaz, and playing the original ending and laughing every time the key changed.

There are a lot of incredibly inspired moments on Forest of Equilibrium. The coda on “Equilibrium”, for example. The solo on “Soul Sacrifice.” Talk to me about the things you really liked then and maybe now.

Lee Dorrian: The songs were pretty much ready to record. When we recorded them, we added things here and there. We did things cautiously—we didn’t want to make mistakes. As for my favorite moments, I think it’s “Serpent Eve.” But I also really like the break in “A Funeral Request.” That bit with the acoustic guitar. To this day, this song just comes into my head. When it goes into that really churning riff that part is pivotal. It’s the best part of the album. It’s a simple thing. It’s just an acoustic guitar over that riff part. That thought came from somewhere else. I’m not sure exactly what, but we were listening to Swans and Dead Can Dance.

Adam Lehan: I’ll just mention that I wrote “A Funeral Request” while staring at a copy of [Witchfinder General’s] Death Penalty, which I laid on my bed for inspiration! [Laughs]

“Soul Sacrifice” was the outlier, at least in terms of tempo and length. How’d that song come out of the sessions? The Soul Sacrifice EP was built around this song.

Lee Dorrian: I wasn’t keen about “Soul Sacrifice” being on the album, to be honest. It’s not on the vinyl. It was only on the CD. I think it clips, too. It doesn’t start properly. To me, that song was an afterthought. Gaz had that riff and I think Griff came up with the lyrics. The lyrics were great. I just didn’t think “Soul Sacrifice” fit the album. Of course, we re-recorded it after and made it longer on the Soul Sacrifice EP. I do prefer the album version. It’s gritty and dark, a nasty sound to it. In a way, “Soul Sacrifice” was the turning point for what was to come next.

Adam Lehan: “Soul Sacrifice”. I just remember Gaz saying, “You’re going to like this one” [Laughs] Again, it was a case of Gaz coming up with something on tape and then bringing it down to Cov, fairly late in the game, too. I think we were in rehearsals with Mike [Smail] when it came up, but it was great. I prefer the album version, too.

Where did the album title, Forest of Equilibrium, come from?

Lee Dorrian: I had the song title “Equilibrium,” but I can’t remember if I had the title or the artwork first. I think I wrote the lyrics for “Equilibrium” and that defined the concept for the artwork. The artwork is based in a forest. The title “Equilibrium” by itself sounded cool, but not esoteric enough. The idea of equilibrium gave me the concept for the artwork, and when I sat down with David, the artist, and told him about the world with two halves. Each side represents opposite extremes. The figure going into these opposite extremes is a neutral — asexual — figure. This figure is stressed going into the light situation and calm going into the dark situation. The backdrop to that is the forest. So, that’s how Forest of Equilibrium came about.

Tell me how Dave Patchett came into the picture. Was he in your orbit at all?

Lee Dorrian: No, he wasn’t at all. We knew we wanted the artwork to be different. We were over the gore stuff that was going on. We didn’t want any of that. We wanted the visuals to be just as different as the music was. We still wanted a macabre aspect to it though. I scratched my head for weeks. I just couldn’t come up with what we wanted as a cover. Then, I thought it’d be cool to get a painter to do it from scratch as opposed to what I was doing with the Rise Above releases like Dark Passages and Revelation. For those, I’d just nicked gothic imagery from old architecture books. But I knew I didn’t want that. I certainly didn’t want the “death metal painters” involved. Someone from the outside for sure. One day, I was walking around the town center — Coventry’s city center is monotonous, just a circle that you walk around and around — and happened to walk down a road off the circle. I noticed a glass gallery exhibiting local artists. I saw David’s artwork in the window, and was instantly drawn to it. His artwork wasn’t fantasy-based but something else. His artwork wasn’t classic or contemporary. It had a timeless look to it. I was very curious about his artwork. I went into the gallery, checked out more of his paintings. David wasn’t there, but his guestbook was. I left a comment in there, saying, “I’m in a band from Coventry. We’re looking for someone to design our album cover. I’m interested in talking to you.” I left my address in the book. A day later, a note came through the door, “I’m Dave Patchett, the artist. You left a comment in my book. I’ll be happy to talk. Here’s my number.” I was living in a high-rise block — a flat — in a not-so-good area of Coventry. Turns out, he lived in the next block. So, I visited and sat down with him with a cup of tea. We had a lot in common. I wrote down a basic couple of ideas, gave him the song titles, and a few lyrics to “Reaching Happiness, Touching Pain.” From that, he did a sketch of an angel with a knife in her heart coming out of a phallus. I remember seeing that going, “Woah! OK, now.” He came around a few days later with another sketch. He literally drew what was to be the album cover. It blew my head off. I knew then he was the man for the job. I think he took about three-four weeks painting the cover. We all went down to this theatre — where he was in this group doing artwork and stuff — to see the finished painting. He did a night there and put it on display. The whole band were at my flat, getting stoned, trying to cobble pennies together for beer. We went down to look at it and we’re totally blown away. That was a solid night. [Laughs]

The lyrics are poetic yet in some cases very pointed. What was your frame of reference back then?

Lee Dorrian: I was really into the Swans. Michael Gira’s lyrics were always great. His moroseness was impressive. I was also into Charles Baudelaire, very inspiring. I don’t think people will understand, but Nick Blinko was a big influence on me as well. I still had a punk outlook to society. “Commiserating the Celebration” is very misanthropic, the way people are shit to each other. My lyrics are stark, almost harrowing realizations. One my favorite lyric lines from the album is on “Reaching Happiness, Touching Pain”. That line “All love is broken / Somber in devotion / The hearse of selfishness has drove it all away.” [Laughs] We weren’t the happiest bunch. We’d all gone through shitty relationships and we were all really broke. Let me put that into perspective. When we had finished recording the album, Gaz and I had a cassette of it all pieced together. When I got home, the electricity had been cut off at my flat because I didn’t have the money to pay the bill. So, I have no light, no heat, and no food. I didn’t even have furniture in the flat. I only had this ghettoblaster with shitty, dying batteries. We listened to our first album on the wrong speed in the fucking dark. How’s that for a celebration? [Laughs] Now, Griff’s lyrics were more funereal. Griff had found a book of poetry by D.P. Barnitz called The Book of Jade. Not long after his book was published, D.P. committed suicide. Really cheerful story, right? Anyway, it’s really opium-based, dark, funeral stuff. Cosmic, but dark cosmic — otherworldly! Griff’s lyrics to Adam’s songs are incredible. Like Griff’s lyrics on “Serpent Eve” and “A Funeral Request” to Adam’s music are unreal. There’s so much mysticism to Griff’s lyrics. He definitely was inspired by D.P.’s prose.

How did you end up at Workshop Studios?

Lee Dorrian: I don’t even know how we ended up there. [Laughs] I think it was Steve Gurney, who’s not credited officially on Forest of Equilibrium. He’s credited as PBL, I think. He’s one of my best friends from Coventry. He used to do live sound for Thee Hypnotics. He was massively into electronic music. He was good friends with a mate of mine named Russell Haswell, who is quite well known in the power electronics scene. So, I’m not sure if it was Steve or Russell who recommended Workshop to us now that I think about it. It’s funny though, ‘cause Steve ended up doing sound for Carcass and Entombed, but that’s because he worked with us. If we had to do it again, we wouldn’t have chosen Workshop. A more likely studio would’ve been Rhythm Studios. We did the first demo there. Also Soul Sacrifice and the Statik Majik EP were done at Rhythm Studios. We never did an album there, though. Not sure why. I mean, Redditch, where Workshop is located, is a quite a rough town. It’s about 30 miles from Coventry. We did weird shit just to get by while we were at that studio. Like Police ID lines to get money to buy beer. We had a massive punch-up at the hotel bar where we were staying. Gaz got his nose broken by some builders just because he had long hair. Griff had got pissed off about the samples — the slowed-down monks — at the end of “Serpent Eve.” He didn’t know that was going on ‘cause he had already gone home. We’d phone him up, playing the monks down the phone. Somehow, he worked out it was us. He phoned The Jesus Army pretending to be me. He acted demented — playing Diamanda Galás — to them on the phone. He gave them the number to the studio. So, The Jesus Army phoned the studio, asking for Lee. They said, “We’re here to help you, Lee. We realize what you’re going through. You can find salvation with us. We haven’t been offended by the call you just made. Please listen to us. We can arrange a meeting with you in Redditch.” He got The Jesus Army to phone me up at the studio. Fucking Griff! [Laughs] Then, there was this copper who’d come down every day. Anyway, we were smoking hash, and we didn’t want him to see that. He knew we were smoking but didn’t do much about it. We were like, “Fuck off!” He used to be in the pop band T’Pau. They had a few mega-hits. I’m sure you know the songs. Anyway, he had left just before they had their first big hit. Here’s this copper just disillusioned about his life choices, hanging around the recording studio, annoying us. He could’ve been a pop star but he ended a copper. Life choices, right? [Laughs] But back to my earlier statement, he was the guy who got us to stand in the Police ID lines. They offered to pay us 10 pounds to stand in this lineup while victims of crimes would ID people. They were looking for the culprits, you see. Here we are in the ID parade. [Laughs] Imagine! We were so broke we did those to go to the pub. And the guy from T’Pau set it all up. Desperate times! [Laughs] We got stitched up though. They offered 10 pounds but we only got five. We should’ve known.

Tell me about the tours in support of Forest of Equilibrium.

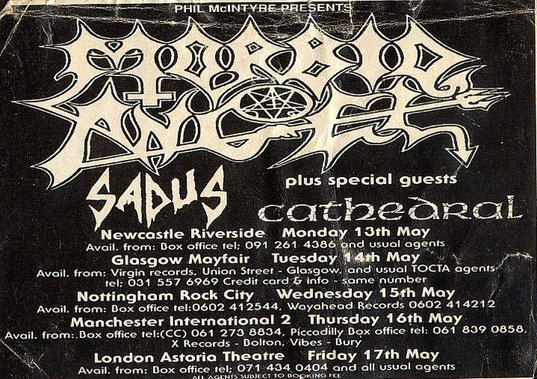

Lee Dorrian: The first tour we did with St. Vitus in 1990. Nobody showed up. We played in Oxford. Eight people paid in. Nottingham probably 10 people. After that, we did a couple of gigs by ourselves. We played really slow. We had Ben Mochrie on drums. We did a tour with Paradise Lost in Holland in 1991. That was a fun tour. They were mates of ours. We were getting absolutely mangled every night. [Laughs] I think Nick Holmes thought I was on heroin but I was really just very stoned. I know this because he asked me if I was on smack. For fuck’s sake, we were in Holland. What else are we going to do? Get mashed and play even slower. Not everyone in the band was getting stoned, but a few of us certainly were. [Laughs] I remember we were in this hotel. Before that we had been in this hash café. We were certainly lit. When we got back to the room, we noticed there were bags in there. We thought, “Oh, that’s a bit weird.” We were so out of it we didn’t really think much of it. We had a few more joints or whatever. Ben looked in the wardrobe and there was this silk purple jacket. He was like, “Man, I’m having that!” [Laughs] He put it on, and I was like, “Woah! Steady on that, mate.” We stopped thinking about what we were doing. There was this briefcase. We opened it up and inside are these arms trade papers. This guy was from South Africa, I think. He was obviously in the country doing arms — like nuclear weapons — deals. Here we are in his briefcase, tossing his papers around the room. [Laughs] We were stoned out of our minds! We left the room all fucked up to go to the gig. Ben’s still wearing the silk purple jacket. Obviously, it was the guy’s jacket, probably a present for someone. In the meantime, the room had been double-booked. The guy had gone back to his room, his briefcase open, and his papers are everywhere. His jacket was missing. [Laughs] So, get this, Nick Holmes comes into our dressing room at the gig, and says, “The police are outside looking for someone in a purple bomber jacket.” We thought he was winding us up. The police did actually turn up. I can’t even remember how we talked our way out of it, but Ben had to give up the purple bomber jacket. I’m thinking the guy didn’t tell the police what was in his briefcase. [Laughs] When we went back to the hotel later, we got a different room, but in the morning the guy was looking in our hotel room window, trying to get good glimpse of us. I think only then were we a bit concerned. What had we gotten ourselves into?! [Laughs] I think right after, we toured with Morbid Angel. That had its moments shall we say. Sadus was on that bill as well. They were cool guys. The shows went down well, if I remember correctly. I think this is when people started to realize who we were. That was the heaviest we ever were as a band. Punishingly slow and extremely heavy. We sold out of everything we had every night.

Adam Lehan: I’ll probably muck the timeline up here because my memory is really bad. We did a UK tour with Morbid Angel, which was… the gigs were great, but it was a weird one! [Laughs] I best leave that one there. Paradise Lost in Europe was great, but I think that was pre-Forest. Marshall Guvnors and Laneys all round. The Marquee gig with Carcass. Carcass, I love those chaps. Still around too, I think.

Forest of Equilibrium is a genre classic. Does that surprise you?

Lee Dorrian: I think we were doing something a bit unusual and a bit special. I’m not trying to sound egotistical. We did think we were onto something with the album. I don’t think I’ve ever felt the same way again. We’ve done loads of albums since, but none of them have had the same individual creativity. It’s quite hard to explain. We never anticipated anything really. I mean, 30 years later, and you’re mentioning Cathedral in the same breath as Sabbath. That’s quite silly. Maybe we thought we’d have a cult classic, but nothing more than that. It’s surprising that it’s held up. It’s my favorite album that I’ve ever been involved in.

Now that you have hindsight, where do you think Forest of Equilibrium sits in the overall timeline of extreme (and not so extreme) metal? Everyone was trying to go faster back then. Cathedral was going in the opposite direction.

Lee Dorrian: We were young, weren’t we? We were into extremes. Growing up in the underground scene is quite competitive. Everyone’s trying to outdo each other. In the beginning, it’s all friendly, but once bands get established, it turns into rivalry. We didn’t want to be involved in rivalry, or anything like that. I think the age explains why we were either extremely fast [with Napalm] or extremely slow [with Cathedral]. If I were to do a band now, I’d probably want it to be extremely slow ‘cause of my age, but that’s already been established, so I’m not sure where I’d go musically. [Laughs] There were other bands that went against the grain at the time, so it wasn’t just Cathedral. I think Forest of Equilibrium is a product of the time, really.

Cathedral links:

1. Decibel February 2006 [#016]. Unreal Cathedral Hall of Fame for Forest of Equilibrium! LINK.

2. Official Site. LINK.

3. Facebook. LINK.

4. Bandcamp. LINK.

5. YouTube. LINK.

6. Twitter. LINK.

More 30th Anniversary Interviews::

1. Corrosion of Conformity – LINK.

2. Carcass – LINK.

3. Death – Human. LINK.

4. Suffocation – Effigy of the Forgotten. LINK.

5. Immolation – Dawn of Possession. LINK.

6. Dismember – Like an Ever Flowing Stream. LINK.

7. Autopsy – Mental Funeral. LINK.