Three years in the making—and over one month of pre-ordering later—copies of USBM: A Revolution of Identity in American Black Metal by Daniel Lake are finally in stock! We’ll start shipping these 544-page hardcover monsters over the next several weeks, but please be patient, as the book’s pre-order has been the largest for any product that we’ve published in our 16-year history!

In an effort to quench your USBM thirst (or perhaps stoke your mania), today we’re sharing our second and final book excerpt, this time focusing on the early days of American black metal cult legends Profanatica.

Profanatica

Paul Ledney’s career in music has been long and decorated (with feces and crucifixes and cum), but it has also been marked by false starts and frustration. In 1986, he played drums in an early thrash/death band called Revenant with guitarist John McEntee, and the pair of them went on to found Incantation together. Ledney wasn’t long for the world of doom-shrouded death metal; he had set his sights on a more ragged, filthier sound, and he turned his creative energy in that direction. Initially, McEntee was on board to play Ledney’s version of raw black metal, but the two young men discovered they had very different goals, and as their creative approaches drifted apart, so did Incantation and Profanatica.

“Our demos came out in 1990,” says Ledney, “but when [Profanatica] split from Incantation, it was basically John McEntee and Profanatica. That was our lineup. Then John McEntee got another lineup for Incantation that was full-time. We wanted to do our stuff part-time, due to laziness at the time. We were kids, you know?”

What began as a primarily semantic distinction between the two bands widened over time due to McEntee’s drive to advance Incantation as a primary focus in his life, while Ledney—though no less passionate about the music being played—envisioned a more relaxed pace for his own work. To Ledney’s ears, though, the sonic differences between Incantation’s death metal and Profanatica’s black metal is, again, primarily semantic. In fact, this judgment ties into Ledney’s entire view of what black metal is… or should be.

“Although I couldn’t imagine growing up without Bathory or [Celtic] Frost or Hellhammer,” he says, “it was Possessed’s Seven Churches, for me and for a lot of the older guys, that started it.” This is just the first of a couple dozen times that Ledney mentions that landmark Possessed record during our interview. There is no doubt: He is absolutely convinced that U.S. black metal has a defined, unchangeable aesthetic, and it can be traced directly back to Seven Churches.

“The triplet riffing, Jeff [Becerra]’s vocals at the time were brutal and much different than Quorthon and [Celtic] Frost,” he enthuses. “If you read the lyrics to that album, that was U.S. black metal. They were calling it death metal then, but the photos, the logo, the sound, the way they hit… And then the Necrovore demo came a year or two after that. And that was black metal for sure. I always say that the first death metal was black metal: the Sodom EP, the Hellhammer EP and Possessed. What people today are calling black/death metal was black metal back in the early ’90s. Even Incantation’s [1992’s classic Onward to] Golgotha is black death metal. It’s evil, it’s got blasphemic lyrics, and they’re hitting hard and going for it.

“You can look at the old Osmose roster,” he continues. “None of those bands besides Immortal have that textbook European sound, with the high-pitched, screechy vocals. There’s no heavy bass present; they’re not hitting hard. I hate it. I hated it then and I hate it now just as much. I always argue with people. That style sounds very feminine. I think those people [who played the European style] had a lot of publicity and it went bigger to the masses, so everybody’s like, ‘Oh, that’s what it should sound like.’ If you go back in time, you’ll see the old way, the way I think and a lot of those other bands still think of what it should sound like. There’s a certain attack that Sarcófago had on I.N.R.I. They hated that melodic shit as well.”

Ledney understood very early which music spoke to him and which music was destined for his garbage can. He describes having some interest in hard rock and mainstream heavy metal, but upon first hearing Motörhead and Venom, he purged anything with less crunch and attitude. He knew what he wanted, and what he wanted was truly heavy black metal.

“Hellgoat, Black Witchery, Absu, Crucifier and other ones… I’m not saying that they’re good and everybody else stinks, but that is U.S. black metal,” he stresses. “That destroys what some people call true black metal, rolls right over it like a fucking tank. The playing is better, it’s heavier, it’s got more feel to it, more soul. Certainly no keyboards. That should be illegal, unless they use it sparingly. I got into this music because it was heavy. I was always looking for something heavier. Somebody like Judas Iscariot, to me, is not U.S. black metal. Whether it’s good or bad doesn’t matter—you can live wherever you want and play whatever you want, but it’s a direct copy of what Darkthrone was doing back then. It might be the best stuff ever created, but to me that’s not U.S. black metal.”

Ledney has similar disregard for the nature-focused bent in some black metal, from either continent. As he says, his comments have little to do with the quality of the music, which he concedes is subjective, but rather whether any of it deserves to be called black metal, a designation that is personally meaningful to him.

“To me, U.S. black metal is more of a style than it is a location. A lot of that [stuff I don’t like] is rooted in folk. Although I’m friends with a lot of bands that play that, they know I’m not crazy about it. The guys look badass with the pictures in the woods, they have a badass logo and the artwork is badass, and then when you hear it, it’s kind of a letdown. It doesn’t kick ass. It doesn’t hit hard. I get that they’re not going for that; they’re going for more feel, but I don’t like that kind of music. I can’t convince everybody that it’s stupid, although I keep trying. But you can’t argue with my point that it’s not heavy.”

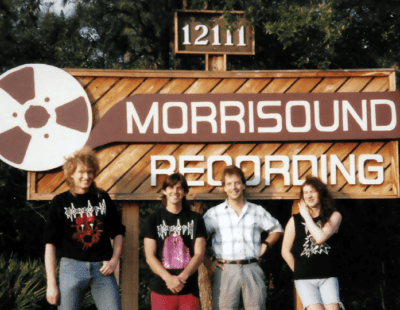

Profanatica clearly had their sonic compass locked into place. They had a few skeletal demos. And with bassist Aragon Amori (also of Demonic Christ, and a comrade of Ledney’s in Incantation) and guitarists Brett Makowski and John Gelso, they had a lineup that was prepared to take Profanatica to the stage. “The shows were pretty sick,” Ledney recalls. “Our set was short because that’s all the material we had. It wasn’t like, ‘Fuck these people, I only want to play a few songs.’ That was all we had to work with. Our first show, I think, was with Goreaphobia in Philly, and back then, shows weren’t every weekend. They were kind of a big deal. So, we went down there and played with them, and I think that the people thought we were joking around up until we were done. We were blaspheming at the first show and people were kind of shocked. They didn’t know how to handle it. They weren’t upset, per se, but they were like, ‘Why were you doing that?’ And we were like, ‘What are you talking about? This is so natural for us.’ Back then, we were 100 percent into it. People were starting to realize that we weren’t kidding.”

For some musicians, the stage is a special place where heightened emotion, vulnerability or theatricality can temporarily shoulder out and replace a performer’s everyday persona, and it can be difficult to balance those competing needs in a social setting like a metal show. Not so for Ledney. “A lot of people ask my wife, ‘Is Paul different off stage? Is it kind of an act?’ And she’s like, ‘No, it’s the same shit; it’s just magnified.’ We talk the same around my family as we would backstage at a show with other bands. I feel that we’re the same; it’s just more magnified on stage, with more arrogance, of course. When we’re done, as soon as I get my clothes back on, I go out and talk to everybody. We’re still metalheads. We’re still part of the people; we’re the same as them.”

At the time, Profanatica stood out from their friends and stagemates in Goreaphobia, Immolation and Incantation. “They didn’t feel the need to put on makeup or blood. Their lyrics were dark—Golgotha has dark lyrics based in blasphemy—they were just more subtle than us. I remember them thinking we were kind of nuts for wanting to do that type of stuff. I guess they just wanted to play the music, and that’s cool, because that’s essentially what it’s about, but they didn’t need any extra.”

Ledney is grateful for those friendships, which have endured through decades, but he also vents his frustration in the way that Profanatica was treated by promoters or other people who were booking shows. When the scene mobilized to celebrate some of its own, Profanatica were often left out.

“A couple times, we rehearsed at Immolation’s studio,” he recalls. “They would play a couple songs, then we would play a couple songs, then Incantation would play. Looking back, it was kind of magical that all three of those bands were together and hanging out. But as the scene progressed and those bands got signed, we weren’t treated very well. It was kind of hard being us back then. We weren’t invited to any gigs. There were benefits and New York death metal shows, and for a couple years it was everybody but us. I’m not really pointing the finger at any one person or band, but all the bands together were doing that. I was vocal—there was no internet, so I would write up a quick letter, like, ‘What the fuck? Everybody but us?’ And then never hear anything. It was Chris [Gamble] and Alex [Bouks] from Goreaphobia at the time that wrote me back and said, ‘We’ll bring you guys to Philly,’ which was pretty cool. When a band is together, they’re pushing their own shit; they’re worried about their own shit, not everybody else’s. But because it was a small scene and more of a tighter-knit unit back then, I was disappointed that people weren’t advocating for us, [people] that we were good friends with. We partied together, we went to shows together, we traded demos and zines together, and when it came time for a show, we were never mentioned. I don’t know what it was. It sucks. I definitely can’t change that fact. I wish I could say it was great back then, but it wasn’t.”

Missing opportunities to blaspheme in a live setting was only one of Profanatica’s struggles, and it may have been related to another sore spot: recording. For months that bled into years, Profanatica limped along on just a few songs, with multiple demos and split releases rehashing the same material. “When we did our demo, we thought it ripped,” Ledney says. “I still like it. But looking back now, two songs wasn’t enough for everybody. So, they just were like, ‘This is the demo? That’s it?’ Incantation had [Onward to] Golgotha, but we just had our demo, and I thought our demo was just as good as their full-length at the time. [But] people needed to hear more of it. Full-lengths made a huge impact, and for some reason I was like, ‘We’re just going to stay underground and have the demo.’ It couldn’t compete with everybody else doing full LPs, and it didn’t really sink in until much later.”

Not that the band didn’t write or record a full-length. Ledney teamed up with Aragon Amori and Demoncy’s Robert Crusen (who took the name Wicked Warlock) to finally bring Profanatica out of demo purgatory. But, it seems, tempers flared to scorched-earth temperatures in the studio.

“We did plan the full-length,” Ledney says. “We recorded it. It got destroyed by the two people helping me and it never came out. I did the drum scratch track, and they took a magnet and erased the reels because they were unhappy with me. It was egos involved. I was saying, ‘You guys should be able to play this shit. It’s really simple.’ They would go to the studio, and the engineer would call me: ‘They came tonight, but we didn’t get anything done. They know the stuff, but they can’t play it in time. They’re messing it up.’ They weren’t really great musicians.”

The loss of that recorded material is one of the great tragedies of Profanatica’s early existence, and one which Ledney mourns for both its impact on his relationship to music and the influence he wishes the album could have had over the direction and perception of U.S. black metal at the time. He has no illusions that Profanatica could have singlehandedly steered the ship away from the European sound that he despised, but he wishes he could have added an early and adamant statement to his side of the argument.

“At the time, the engineer was like, ‘I think you should ditch these two’ [for] another guy who played on our demo, ‘and just finish it no matter what.’ I was beat down after I found out it got erased. I needed a break. I put so much time and effort into that. It took a long time for me to bounce back from that. I’m thinking at the time, ‘I used every blasphemy I could think of.’”

That, of course, is just a drop in the bloody ocean of USBM’s deep, dark history. For the rest of the story, order you copy of USBM:A Revolution of Identity in American Black Metal here.