GWAR has become such a staple of the metal landscape that many listeners don’t realize there was a time they played for handfuls of people in their hometown. In the early years, GWAR was more an eccentric artist community in Richmond, VA than a band. At the time, young artists Hunter Jackson and Chuck Varga dreamed of making a film called Scumdogs of the Universe. But when they hooked up with a punk musician named Dave Brockie and his band Death Piggy everything changed. Working together they cobbled together the earliest formation of GWAR, a band that ultimately became a heavy metal juggernaut composed of interplanetary marauders who sacrificed public figures including Barack Obama, Sarah Palin and Monica Lewinsky onstage and somehow earned the love of everyone from Fox News to the science fiction fan community.

That said, it was a long crawl to get there. Throughout the late ’80s, GWAR had a rotating lineup and needed to scrape to get parts and equipment for their now famous Slave Pit. They recorded their debut Hell-o! and toured relentlessly. By the decade’s end, things started to gel with a steady lineup and a crack team of artists. The band toured, wrote, improved and slowly introduced their perverse extraterrestrial madness to the world. Scumdogs of the Universe was the defining step. The album turned GWAR into a cultural commodity that insulted GG Allin on Jerry Springer, argued with the late Wally George on Hot Seat, appeared and was deified repeatedly on Beavis and Butthead and hung out with Joan Rivers.

Scumdogs also showed them evolving into mature if unconventional heavy metal songwriters. While Hell-o! was unpolished and inconsistent, Scumdogs was a complete effort that included well-structured songs, competent production and touches you just didn’t hear on many if any metal albums in the early ’90s (bassoons, anyone?) “The Salaminizer,” showcases Brockie’s lyrical panache with a section cribbed from N.W.A (This is your ass, and I’m in it/ My man Sexy will fuck you up in a minute/ With an axe, sword, mace, pike you’re limbless/ Then I’ll fuck your ass till it’s rimless). Band members who weren’t even musicians were weaved in seamlessly on tracks like “Slaughterama” and “Sexecutioner” and “Sick of You” is now a GWAR staple. Scumdogs is, in many ways, GWAR’s version of KISS Alive except that it took place in a studio. The record wasn’t meant to just be a listen but rather take fans to the world GWAR brought to life at their concerts. Scumdogs of the Universe is performance art as a record as well as raucous, fist-pumping revelry.

The Scumdogs period from 1988 to the album’s 1990 release was a time of startling growth and creativity for the band. It’s when they became serious about their music, spent more time in the studio to build an immersive show and utilized all of their artistic skills to build elaborate props and present ridiculously over-the-top shows. Despite going against if not outright mocking every trend the ’90s produced (anyone remember Len or Days of the New?) GWAR became one of the biggest underground bands of the ’90s and in 2020 is still going strong despite the untimely death of Brockie, known to most listeners as Oderus Urungus.

It’s time to tell the tale. Decibel corralled more than a dozen people who were there to remember the Scumdogs era. Sadly, Oderus is not here to help but his hijinks will live on forever in the following stories. We’re happy to present you the exhaustive oral history of GWAR’s roughly two-year Scumdogs era in conjunction with the 30th anniversary reissue, from the road to the studio to the New York showcase where they were discovered by Metal Blade to the album’s reception and enduring legacy. There’s a lesson in all of this: No matter how irreverent your art is there is an audience waiting, especially if you have cool costumes and drench your audiences in fake blood and semen. Onward to Scumdoggia!

PART ONE: A JUGGERNAUT TAKES SHAPE (1988-1990)

The two-year period before Scumdogs was all about work. The band toured relentlessly in an old bus, added artists to the Slave Pit and worked hard to realize their vision. At the same time they juggled everyday jobs and responsibilities in their Richmond, VA hometown while they pursued their dreams. That work on the road and in the art studio paved the way for Scumdogs.

Where was GWAR as a band in the period before Scumdogs and where did you want to go?

MICHAEL BISHOP (BEEFCAKE THE MIGHTY, BLOTHAR): Right before Scumdogs came out is when we realized this wasn’t going to just be an art school project that went hideously awry. Even though there was a big music school at VCU all of the good music was coming out of the art department. We made Hell-o! [in 1988] and toured on the punk rock circuit carved out by Black Flag, the Dead Kennedys and Circle Jerks. At the point GWAR transitioned we got into the sounds of bands like Celtic Frost and crazy German stuff. We were thinking about writing more metal music. We wrote a set that became Scumdogs.

MIKE DERKS (BALSAC THE JAWS OF DEATH): I joined right after Hell-o! came out. I figured I’d join this band, get a trip to California, and it ended up being the rest of my life. The first GWAR show I went to was after they kicked the first guitarist out. They were only playing shows like every six months or so. It was chaotic and weird. I sat on the side of the stage and was like “this could be fun.” It wasn’t what I saw myself doing with my life, but I could see the potential for something cool. When I joined they had thrown a band together to make an album. The first guitarist had some personal issues and I was already jamming with Bishop so he asked me to join. When Brad Roberts joined on drums we felt like a more solid, real band and could concentrate on the music. None of us knew what metal was and Scumdogs was sort of an attempt at “this is what we think heavy metal is.”

BRAD ROBERTS (JIZMAK DA GUSHA): Derks was in for about one U.S. tour and they came back from that tour and decided they needed a new drummer. Based on those tours they had some notoriety and were a hot item but they needed a new drummer because some offers were on the table. That’s when I auditioned — probably around late 1989. I was in a local band and knew of GWAR but had never gone to any of their shows. I’d seen Dave Brockie’s punk band Death Piggy before he started GWAR. But GWAR was a little elusive and in and out of town a lot.

The first time I saw GWAR was from behind the kit. I knew Brockie as a crazy stage performer and I’d seen pictures but I’d never seen it in the flesh. The first show was an amazing cataclysm event at the Cedar Crest skateboard ramp.It was a steel covered ramp in the middle of this country club kind of near the DC area (in Centreville, VA). We played on top of the ramp. Tony Hawk skated there once. The first show combined GWAR and one of the best known skate spots on the East Coast at the time. It was almost like a little skate utopia.

BOB GORMAN (SLAVE PIT ARTIST): I was very into the local music scene. I wasn’t a musician as much as I loved punk rock and weird music. I saw them at the end of 1987 with the Butthole Surfers and it was life changing. They crucified Santa Claus. It was really dark and weird. I was in art school and had no idea what I was doing. My teachers were all pretty square. When I saw that show I knew that was the stuff I would like to do. I went to a party afterwards right across the street from where GWAR played. I remember complaining about art school and talking about how great the show was. Bishop told me I should help out and make stuff.

HUNTER JACKSON (Band co-founder, TECHNO DESTRUCTO): We were all very committed to what we were doing and sure that the world would open up for us. The catch was that as individuals we had different goals. But it was a wild, fun time full of angst and anger. It was very much like being part of a pirate crew where our ship was a school bus painted grey and we traveled from city to city and fought a huge battle and got all bloody, then loaded up the ship and moved out to the next show.I knew that there was a whole world of crazy people out there who were into the same weirdo shit I was. I used video and comics to let fans know that there was this whole world of GWAR full of interesting characters that were funny and scary.

CHUCK VARGA (SEXECUTIONER, ARTIST): I met Hunter Jackson in the early ’80s after we both finished art school. We collaborated on a bunch of projects together that involved everything from costumes to superheroes — everything cosplayers get into today. We would go to conventions to shop our wares and rub elbows with people. Eventually we decided to do something more ambitious almost like John Waters except with all the things we liked. We started to combine all these ideas about guys from space with punk rock. Scumdogs was when we really started to work out the GWAR concept.

MATT MAGUIRE (SLAVE PIT ARTIST): I was still in high school. I probably met Jackson and Don [Drakulich] around 1987. Everyone remembers their first GWAR show. Back then who was doing anything like that — maybe KISS? Scumdogs was when I started hanging around the Slave Pit on a regular basis. It was such a crazy and formative time because nothing was too passé or stupid to do.

DON DRAKULICH (SLEAZY P. MARTINI): We felt we could do better [than Hell-O!]. We were full of ourselves and expecting a bigger label to sign us. We were expecting and hoping to be on a bigger label. But at least we got to a bigger studio with 16 tracks.

Could you share any memories from when you worked the punk concert circuit?

BISHOP: GWAR, on the road in the early days, was the craziest thing anyone could imagine. I’ve said this before but it is worth repeating: People had no idea what to expect. We’d pull up in El Paso, TX or Greenville, NC and would play these small venues. You’d see GWAR on these tiny stages and we never compromised on the setup. People just reacted to it with utter astonishment. There would be maybe 15 people there who probably would have been there anyway. During the day Hunter would get on roller skates and go to the cool part of town and hand out fliers and try to get people to go to the show. We’d start playing to these crowds that had no idea what to expect. It was like someone checked a box that said “anything is permissible, you can do whatever you want,” because that’s what we did.

There was a transition period where we realized our props were falling apart after every show. We had to come up with better technology and we couldn’t destroy monitors and rebuild costumes every night. Some of the shows were one-off events and we couldn’t repeat them. We had to find a way to take that crazy show on the road. It was almost like Ken Kesey’s acid tests. GWAR was never a stripped down rock band, even when we’d play the dining hall at Princeton or a sandwich shop in East Carolina University or the tiny stage at CBGB.

DERKS: We called up venues at the backs of fanzines to find shows.

ROBERTS: I remember doing two two-week tours, one to Canada and one around Texas and back. After that we came back and recorded. The tours were crazy. I was just 21. We were in an International Harvester school bus with the seats ripped out and bunks welded in. We were kids with no money doing crazy art. I learned how GWAR toured and it was the ultimate adventure. I got my first taste of Mardi Gras and Texas. I was the straight edge kid — I stopped drinking and smoking weed after high school and focused on the music. I think that’s what they liked with me. I wasn’t riddled with drugs all the time. My playing seemed to elevate them because I was all about the playing.

JACKSON: As a redneck punk rocker who grew up in the swampy air of the sticks outside of Richmond it was super exciting to be able to go to comic book stores in cool cities like New York and San Francisco. I was collecting Japanese manga books and saved money the whole trip to blow on comics I couldn’t even read! They were a huge inspiration for what I wanted to do with GWAR. I wanted GWAR to be like a pizza that combined all the geeky stuff I was into in one big head on collision that splatters all over anyone standing too close.

DANIELLE STAMPE (SLYMENSTRA HYMEN): Hell-o! was made around 1988 which is when I joined. GWAR had started touring up and down the East Coast. My very first show with GWAR was with the Butthole Surfers and it was terrifying. We also played at Danzig’s very first show – I can’t remember if it was New York or New Jersey.

What were your lives like outside of the band at that point?

DERKS: We were all in on the band but we all had to work. We were putting money into the band at that point to be able to go on the road.

ROBERTS: We all had jobs then and we still have jobs to this day. We’re a household name but no one is a rock star. It’s no different today than it was then. I was doing construction and had to drop out of college to go on tour because they had so much on the books. I thought I’d do this for a minute and get back to school and 30 years later it never happened.

JACKSON: I was working at a shop that made artificial limbs. It was near the Slave Pit and we were always dumpster diving because they were always throwing away fascinating, mysterious objects that I might use in my sci-fi movie sets and costumes. I eventually applied for a job and they hired me. I learned a lot about techniques and materials that I applied to my experimental GWAR costumes. As we started to tour more and take a lot of four day weekend trips I got fired. I went straight to their competitor and was hired. Eventually I worked for a guy who actually let me bring my GWAR stuff into the shop and work on it.

DRAKULICH: I don’t remember a life outside of it! We partied when we worked and we worked when we partied. I would go across the street and hang out at a club called the Metro. There was a happy hour special and I would always get a tuna steak burger and a pitcher of beer. That was my sole source of entertainment and socialization. The artists were going 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

STAMPE: I was a VCU art student. I was also learning how to faux finish and apprenticed under a master faux finisher. In the ’80s and ’90s Richmond was in the process of returning buildings to their original grandeur. I did a lot of work at the The Jefferson Hotel. Most of us were living in these little 1880s row-houses. It was an artistic community with a lot of different bands. Around 1989 is when GWAR really started solidifying. The band exploded pretty soon and we went from touring in a school bus to touring in a real bus.

Was the Scumdogs period the time that the Slave Pit coalesced?

JACKSON: It was certainly a time when we started to get more focused and streamlined. It was hard to find musicians who were willing to commit to make it a success. The crew we had were dedicated and determined to make it work and if you weren’t willing to keep up the pace you might be replaced.

GORMAN: I became a full time member at this point and we started working on costumes for the Scumdogs photo shoot. I was busy making the parts for the Balsac legs.

MAGUIRE: That’s a good assessment. It’s when it really started to become something. The characters came into their own around Scumdogs. All of a sudden it was like “there is a record deal!” That time solidified what GWAR would become.

DRAKULICH: We became a more professional organization. Moving into a larger studio was a big help. We started to add more people at that point — probably more people than we really needed. We toured with like 18 to 20 people sometimes. It made making money nearly impossible.

What artistic influences helped further develop the characters around Scumdogs?

MAGUIRE: Wrestling, Star Trek, sci-fi. It was a mix of all these different subcultures.

PART TWO: WRITING AND RECORDING SCUMDOGS (1989)

After releasing their debut through Shimmy Disc Records in 1988, GWAR signed with the English label Master Records. Much of the material was already in circulation but needed to be refined. The album was recorded in their Richmond hometown but featured their first taste of the real musical world: a professional studio and a producer who both forced them to improve their chops while encouraging experiments that would make the album sound that much more far out.

How did the songs for Scumdogs come together?

BISHOP: Sitting around in our rehearsal space being broke and hot and miserable. I remember going into a space in the basement that was kind of cool to work on riffs. I did a lot of writing with Derks. It was like we were trying to do GWAR’s version of Celtic Frost even though we didn’t know the vocabulary of metal. We were not metal musicians. We were punk musicians. Our appreciation for metal was real; we just weren’t steeped in it.

DERKS: We started bringing in some of these weird, alternative influences from both metal and punk rock. We’d been touring so much between Hell-o! and Scumdogs — we did like four U.S. tours in that time. We’d been playing these songs on the road for like two years before we got to the studio. The songs definitely changed a little bit in the studio and a few arrangements were changed.

JACKSON: The artists and the musicians spent a lot of time at the Slave Pit. There were many intense brainstorming sessions where we would come up with crazy ideas for the next show. “Cool Place To Park” is about (former GWAR guitarist/artist) Dewey Rowell trying to park a fucking school bus in New York City. It was funny to translate that into GWAR with a video where Beefcake is driving a chariot pulled by human slaves down the highway with truckers honking at him for blocking traffic. A lot of the guys were H.P. Lovecraft fans so the “Horror of Yig” is about seeing a monster so horrible that you are never the same. We played a lot of geeky war games in the Slave Pit and “Death Pod” is about a vehicle from those games.

DRAKULICH: The material was written before they got to the studio although since I’m not a musician I might be misremembering it [laughs]. It was just getting time to record it.

STAMPE: We would have Monday night meetings where we would discuss a lot of different show ideas. A lot of things were from the band jamming and could turn into something else when the artists got involved. We would think “this song would work well for the fire dance” or “this song would work well for a decapitation.” “Sick of You” came from the tour bus because we were so sick of each other. It was art imitating life [laughs].

At the same time you began working on Scumdogs grunge started to emerge on the West Coast and would eventually take over music. Were you paying any attention to it?

DERKS: We didn’t really notice it until after Scumdogs came out. Our influences came more from pop culture and strange ideas. GWAR was anti-grunge. They said it wasn’t cool to put on big rock shows and [performers should] go on stage in jeans and a flannel shirt and ignore the audience. What we were trying to do is bring coliseum shows into tiny clubs, which usually had energy but no visuals.

ROBERTS: Grunge didn’t even pop off till about 1991 and we were already working on America Must Be Destroyed. GWAR never wanted to be mainstream. Grunge was just palatable enough for America and was the new wave of sound. We always worked in the shadows and we weren’t too concerned.

You mentioned that you learned the metal idiom by writing Scumdogs.

BISHOP: That’s exactly right [laughs]. Even on records like Violence Has Arrived, which definitely has a metal sound, you always have Mike Derks doing his take on metal music. He’s a very unusual musician and a lot of the songs like “The Salaminizer” are a product of Dirks’s style plugged into metal.

ROBERTS: Punk was where we cut our teeth. We were between DC and Raleigh where the big hardcore explosion took place with Minor Threat and Bad Brains on the East Coast. The stuff struck a chord with all of us. Later on I’d get into King Diamond but that was when we were already in GWAR. Early on, though, that’s not the stuff that spoke to us. I was involved in writing very few songs on that album: “Maggots” and “Salaminizer.” Those weren’t written yet. The rest of the material had been out there for a while.

Where did the idea of riffing on N.W.A (the lyrics of “The Salaminizer” borrow from “Gangsta Gangsta”) come from?

BISHOP: That was 100 percent Brockie. I remember the first time we heard that record [Straight Outta Compton]. We were smoking pot at a venue in Holland waiting to play. There was a bunch of vinyl near a record player. The minute the needle hit that vinyl it was the same reaction we had to hearing the Sex Pistols. It was heavy. Dave didn’t listen to a lot of hip hop but he listened to particular hip hop. GWAR worked on art all day and there was a big studio, a shop with tons of stuff going on. The boom box was always playing and we’d listen to Jesus Christ Superstar, especially because a lot of the visual artists liked ’70s music. The N.W.A record was in constant rotation along with Black Sabbath and Dead Kennedys.

What do you remember about the studio sessions?

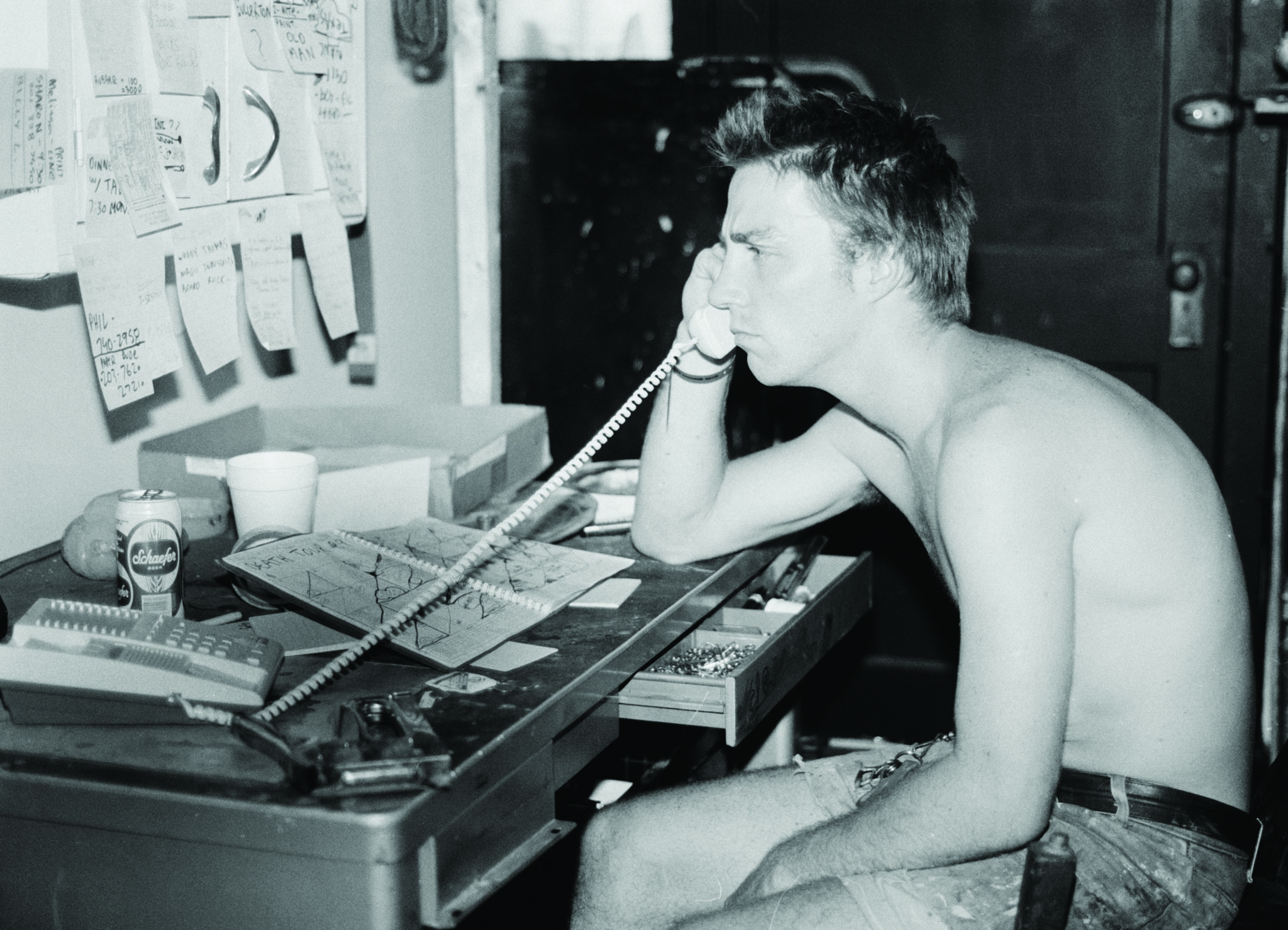

BISHOP: The album was recorded at Alpha Audio on Broad Street in Richmond. It was only a few blocks from the Lee Monument. It was a label studio for RCA in the ’70s and had the best Richmond engineers who’d been doing it for a long time. It was the only professional studio in Richmond then and they did a lot of ad work. We were in there with all the jingle writers. It was a lot of fun. Looking back, it was probably a pretty idiosyncratic space. Studios now all feel the same.

The studio was well known for this guy Robbin Thompson who wrote the song “Sweet Virginia Breeze.” He was the main jingle writer. We were definitely an odd fit but the guy who owned the studio, Nick Colleran, understood what we wanted to do. If you went in his office, he had a shit-ton of gold records. We spent maybe a week doing the basic tracks and Dave spent maybe a week doing vocals. We definitely spent a little more time then you would now but it was still on the punk model.

DERKS: It was off Broad Street right across the street from a fried chicken place. Ron [Goudie, producer] made us promise not to eat any fried food before we recorded. He said: “you need to eat salads!” Later he’d find me across the street eating a bucket of chicken. It was my first time in a recording studio. Ron had this thing where you would take a song and slow it down to half speed to see where the bumps were and where things didn’t fit. When you play full speed you don’t hear them. That’s something I still do to this day — play songs at half speed.

ROBERTS: It was terribly painful. Every recording session I’ve done with GWAR is like that except for the last one. Alpha was later turned into an insurance place for drunk drivers. But it was a great room and you could put a whole orchestra in there. I think the design of the room is still intact. Their money came from commercials. Robbin was the A&R guy trying to get the local stuff in the studio. I don’t think they understood us. But if you spend the money, you get the session time.

When did you decide to involve as many members of the pit and the GWAR universe in the album as you could?

VARGA: The “Sexecutioner” song was my idea. I fell in love with the song so much and begged them to let me do it [laughs]. I was only there for my sessions. I’m an artist and I got thrown into the world of songwriting. I had never done anything like it. Brockie was there to sort of cheer me on. Even though, at first, it didn’t seem to be that put together, over the years it’s turned out to be a Shakespearean classic.

DRAKULICH: When it came to my song (“Slaughterama”) they only let me track the vocals that were needed and then they threw me out [laughs]. I was like “hey I’m just getting warmed up!” As I would later find out, that’s a typical response to non musicians.

STAMPE: I was a lot of more involved with the logistical side, so I just came in to do my backup vocals. At that point ,Brockie wanted to be a serious band. I do have a musical background: My mother was a concert pianist in childhood and my grandparents were circus workers. I was a chorus geek in high school and played piano. The high operatic parts I did in “Maggots” were my idea. I called it a “wailing mermaid sound” [laughs].

Did Ron Goudie help develop and move your sound forward?

BISHOP: It was the first time we worked with someone who would qualify as a real producer. He definitely had some music school ideas about doing things. He’d make suggestions about bass lines — and they were good — about not hanging around on the root and messing around with the third and building chords. He helped me understand music in a way I didn’t. We were all self taught except for Derks, who could read music but read slow. He was actually in music school although he dropped out. He’s since done scores and notations for GWAR. But he was the only one. Brockie and I were self-taught.

ROBERTS: It was the first time I ever worked on the click. Ron died recently from liver cancer. He taught me how to play drums on a real record. I’d done tons of demos and EPs but that was the start of me getting into the music business. Before Ron, if you listen to the drums on Hell-o!, it’s super messy and the tuning and tempo is all over the place. It’s a chaotic mess. When they got me, I was the timekeeper and Ron put me on the click and everyone had to play to me. We realized we had to figure out specific rhythms and it really helped GWAR.

There are a lot of different and unexpected instruments and sounds on the record, including bagpipes and bassoons. Was it difficult to get those sounds on the record or was everyone on board with the approach?

BISHOP: The label was far away and uninvolved. Ron certainly pulled out some L.A. producer tricks. Some of that is how it got away from how it sounded in the room. I always wanted “Love Surgery” to have a Slayer bite and I always wanted a bass sax on there. [Ron] said a bassoon was much cooler. But nothing with a clarinet is cool. Ron definitely sharpened some of the sounds we were able to get and did a good job tracking the drums and bass. It’s how I’ve tracked bass since then.

DERKS: We were supposed to have a sax solo and it’s a bassoon. We got a music student from VCU to play on a metal album. It was just improvised.

ROBERTS: We had ties to VCU and the music and art department and Ron was going to exploit those relationships. We used timpani and screamed into the timpani and had bassoon players and bagpipes. He went all out — he wanted to have all of these crazy sounds from the GWAR world represented.

PART 3: DISCOVERED IN NEW YORK (1989)

In the run-up to Scumdogs, GWAR spent a lot of time going to music shows and conferences and meeting label executives to find a right partner to expand their footprint. Although GWAR was already committed to Master Records for Scumdogs an appearance at the in New Music Seminar in New York would prove pivotal to their career. At the show, the band met executives from Metal Blade Records, where they have remained for the majority of their career.

You were signed to Master Records but also signed a distribution deal with Metal Blade during the Scumdogs era. How did that happen?

BISHOP: I don’t know how we came to Master’s attention. The label was started by this guy named Buster Bloodvessel [Douglas Trendle] from the band Bad Manners who were sort of a second or third wave ska band. One of the first things they wanted was to get an American band on their label and we fit the bill. I do remember the general attitude [at the New Music Seminar] that we were a band to see. There was a lot of interest and we were talking to a lot of people. They thought we’d be huge in Japan because we had a bunch of interviews with Japanese television. The show was kind of a weird experience and it wasn’t the best show we’ve ever done. I remember thinking we had kind of bombed it but people thought it was great. I don’t remember meeting Brian [Slagel] or Mike [Faley] from Metal Blade. It wasn’t until I became a music academic I realized why Slagel was interested. His position in metal is huge. He’s an important character in the story. He has a long tradition of identifying cool stuff and bringing it out.

DERKS: Metal Blade brought the right to distribute the album in the U.S. My first memory of meeting Metal Blade is that they took us out in Times Square when it was sleazy. What impressed Dave was that they gave him a handful of quarters and set him loose to the porno booths.

STAMPE: I was there with Brockie and Sexecutioner. We could go to things like that and basically dance around in our costumes. It worked. We would show up at record labels just to do PR and sell ourselves. There was one [appearance] that Dave said I blew because I came out with a bloody crotch (Ed: Legend has it Stampe broke a blood capsule in her codpiece during a meeting with Relativity Records, costing them a potential deal).

BRIAN SLAGEL (FOUNDER, METAL BLADE RECORDS): Back in the day there was this college radio music convention that had a big metal presence. GWAR had played another show and people told me I had to see them. I saw them and they were absolutely incredible and I said I have to work with them. The word before was that they were a band with this amazing show but they weren’t very good players and the music wasn’t very good. But when I first saw them I thought the music and songs were great. I was into the whole package at once.

They had signed earlier with a company so we actually just licensed them at first. I didn’t hear any of [Scumdogs] until it was finished but I thought it was amazing. I said we had to promote it because it was so unique and different. It was this mixture of punk and metal and comedy that no one had heard before.

MICHAEL FALEY (PRESIDENT, METAL BLADE RECORDS): They played the New Music Seminar and just torched the place. This is a place where you went to be seen. There were all of these shows going on. The band that stood out was GWAR. Brian talked to me and said we had to sign the band. It was more than the music but the music is what held it together. In 1989 people were coming out of hair metal and grunge was coming in, so they were in this grey area. They just caught on with a lot of different fans because they crossed across all genres. I remember [the show] being so over the top and so much happening — Sleazy P. Martini in one place and Dave Brockie in the other. Every person was a character. When the blood started coming out all over everyone, I think that was the seller.

What do you remember about meeting Dave Brockie?

SLAGEL: He might not have been the first person I met — it was either Bishop or Dave. I quickly realized they were very sane people. But [Brockie] was really interesting because he had so many ideas. Sometimes there were sharp political overtones in songs and people didn’t even catch on. He was one of the most creative people I’ve ever met in my whole life — a tour de force.

FALEY: I met him while he was still in costume as Oderus Urungus. You quickly realized that all of it was thought out and he was this brilliant guy. That’s what struck you — they had big ideas and were very smart and knew where they wanted to go.

PART FOUR: RECEPTION AND LEGACY (1990-PRESENT)

Scumdogs of the Universe was released on January 8, 1990. Throughout the ’90s, GWAR’s profile grew and while they never achieved superstardom they have become an unlikely part of America’s pop culture milieu. Thirty years later almost everyone involved says Scumdogs allowed that to happen.

Do you remember how Scumdogs was received?

BISHOP: Thankfully a lot better than Hell-o! was received [laughs]. People liked it and I think we were surprised by the sound. The remix we have now [for the 30th anniversary reissue] is such a breath of fresh air. Derks and I were so young when we were in L.A. listening to them mix the record. It was like we were invisible. We didn’t have a say in how things were turning out and we weren’t old or experienced enough to assert what we thought. We knew it didn’t sound like we sounded when we were in the room. Even though we didn’t think it sounded as good as it could when it came out, people were positive and we started seeing a lot of momentum. We got on MTV, we got on Beavis and Butthead. Those things came from this recording. It’s when we started taking off.

DERKS: Well, you always think there is a one point where you break and become huge but with us it’s one progression to the next. I don’t remember seeing a ton of press on Scumdogs and the shows didn’t explode after that. It’s always been gradual. I don’t remember it being a huge step. I do think it’s when a lot of people became aware of us and so it has a lot of meaning for our fans. From the outside it’s probably easier to see.

STAMPE: Unfortunately with the costumes, some people still said, “but the music…” Honestly though, the musicianship is incredible, especially when you consider the stamina you need in the costumes to play those songs live.

FALEY: With Scumdogs, you got a much better delivery of their music and they also utilized a lot more members of the band like Sleazy and Beefcake. Some of the people who got Scumdogs hadn’t seen the live shows. What the record did was almost present a live show and introduce all of these characters. You knew that “Sick of You” would be a standout, although I never thought it would be performed in every one of their sets 30 years later. People now say it’s one of the benchmark records in shock rock history and that’s quite a statement with the likes of Alice Cooper out there. GWAR just took it to a whole new level.

In a way it’s a cultural benchmark — the moment GWAR became the band people know today.

BISHOP: [Laughs] What a weird cultural institution! I think we always just thought if someone said we shouldn’t do something we should do it. At the time, it was all different.

JACKSON: It was a point where we got all the elements of the show together: how to make the blood shoot 15 feet; how to build dynamic suits that look awesome from the back row; how to write a show that has a beginning middle and end, crammed full of funny social commentary and interesting characters, but most importantly, is still fun even if you don’t pick up on any of that.

What is your favorite song?

BISHOP: It’s changed over the years. “Maggots” is a really good example of us trying to be a metal band. That song sums up what we were trying to do. “King Queen” is another one and a perfect example of a Dave Brockie song. It’s so freaking funny.

SLAGEL: I knew you would ask but it’s a difficult question. “Sexecutioner” came on my phone randomly yesterday.

ROBERTS: I like playing all of our songs, even the ones from this that we put on a record 30 years ago. “The Salaminizer” has a special spot because it’s one of the first things I helped arrange and record with Derks and Bishop.

JACKSON: “Sexecutioner.” Varga wrote the classic lyrics for his character. Sexy was a good bodyguard and best friend of Oderus. He was a more refined masochist, savoring every disgusting aspect of his victim’s demise. In contrast, Oderus was all impulse and violent self-destructive, self-indulgence.

What is the legacy of Scumdogs of the Universe three decades later?

BISHOP: It’s the moment we announced ourselves to the world. That’s what records are. It’s a capture of a moment in time. GWAR was very unique and it captures this unique thing very early in its inception. It has flaws, but there have always been flaws. The reason this record stands is that GWAR stood against the boring presentation of rock music where people were just on stage in street clothes. GWAR was so unique that people couldn’t imitate it.

DERKS: It is the defining GWAR album. It’s the album where we defined the core concept. We had four or five years leading up to that, and after that we headed into the wilderness of what GWAR could be.

ROBERTS: Scumdogs was definitely when GWAR became a rock band and discovered the platform for our art.

JACKSON: [The record showed] that a whole bunch of driven, multi-talented people can strive together toward a common goal. Through determination and perseverance you can achieve a lot more than one person struggling alone against the odds. I’m proud of what I was able to achieve through GWAR because it was against the odds in spite of opposition and in the face of all the people who didn’t believe we could do it, or just thought it was stupid. We did it anyway.

VARGA: On Scumdogs we had a record label and had to work with adults. We were just trying to push forward the idea of what you could do with art.

MAGUIRE: The creativity came from every single person who was there. If one of those people wasn’t there, it wouldn’t have been the same experience at all. Scumdogs opened the door for people to think this art project/band could be a thing.

DRAKULICH: Scumdogs is where the look and the characters were cemented. The blueprint was established. Before that, it was still being worked out and characters were coming and going. We figured out everything on Scumdogs.

STAMPE: It’s probably everyone’s favorite GWAR album. Hunter always used to say: “Don’t talk about, do it.” That was a big thing in the Slave Pit. We were big fish in a little pond [in Richmond] and there wasn’t a lot of distraction in our town. I’m not sure we could have pulled this off if we lived in Los Angeles. I think that attitude rubbed off on other people in our community. We couldn’t have done this without our community pitching in.

SLAGEL: It’s a pivotal record that came at an unbelievable time. When it came out in 1990, it was just such a strange time in music. For them to come up with something so fresh, so different and so cutting edge that lasts to this day is a testament to them.

Would you change anything?

DERKS: We just did! [laughs]

ROBERTS: We did! People should go buy the remaster because this is how we intended for fans to hear it.

GWAR’s 30th anniversary editions of Scumdogs of the Universe are out October 30 but are available for pre-order now! GWAR will also perform special 30th anniversary livestream of Scumdogs on October 30. Get your tickets here!