DES GOÛTS ET DES COULEURS ON NE DISCUTE PAS

I was talking music with a co-worker of mine recently. She’s a Juilliard trained classical pianist with an extracurricular taste for light jazz, neo-soul, trip hop, (coffee shop music essentially, you’ve heard this stuff.) We chatted about the ‘Franks’ we both dig (meaning Liszt, Poulenc and—thinking we were very clever—bebop saxophonist Frank Morgan,) for a few and the peculiar mindset of career, classical musicians until she suddenly pulled the colloquial railroad switch with an exasperated punch in my shoulder. She’d always known me as ‘the metal guy.’ Why hadn’t we had this conversation before? Why hadn’t I expressed to her how broad my musical appreciation was before now and what even was it with me and metal in the first place? She was genuinely puzzled by what she interpreted as my deeply incompatible artistic biases. Isn’t metal essentially a mausoleum for adolescent fantasy? Isn’t the bulk of it just pompous onanism or knuckle-dragging chauvinism or both? How could that form the framework of my listening diet which also included so many sequences of music that she understood to be qualitatively good? She couldn’t square it.

Barring the elbow room right then and there to make my case via a few selections of what I deem ‘gateway metal,’ (specific passages by Opeth, Intronaut and Enslaved have always pretty effectively done the trick for me,) I preached on the tremendous liberty the genre exudes; the unparalleled elasticity that functions as the flex to keep the old pillar so resilient. Consider any melodic discipline or artistic value, I promise that it can be adequately rephrased if not directly woven into metal’s fabric; it has a knack for stylistic reconciliation. And anyway, classical music’s riddled with quixotic and arguably puerile themes, (hell, one of its most basic forms is called fantasia,) and Lizt—for one—could be almost barbarically aggressive, you kidding me? (That’s a slight overstatement—Lizt was no Bartók—but whatever, I had her; or at the very least she was swayed.)

That evening as we waited for our ride to collect their things and say their goodbyes to the staff she rounded on me. “Hey, play me something. I’m interested in hearing some of this stuff from your point of view.” Completely unprepared, ladies and gentlemen. My mind had been entirely occupied with calculating how many hours of sleep I could reasonably expect before I had to hoist my—in all likelihood howling—son from his bed in the morning in order to prep him for school. Shit.

“Um, sure. Give me a second,” I hedged, scrolling quickly through the library of albums on my phone for a worthy specimen.

“Don’t sanitize it for me,” she protested. “Just play me the last thing you were listening to.” And with my phone quickly wrestled from out my hand she pointed to the play button at the bottom of the screen. “Today Is the Day; are they metal? They sound kind of like an ‘80’s straightedge band.”

“No, they’re metal. Tangentially, I mean.” Fresh off the heels of reviewing the band’s No Good to Anyone release I’d been revisiting Today is the Day’s back catalogue incessantly for the past week. The album I’d been occupying myself with on the drive up to the event was Willpower, a record that is—to me—the very objectification of idiosyncratic hostility. ‘Gateway metal?’ Not hardly. Not by a fucking country mile.

“Good enough,” she smiled, pressing play and handing the phone back over. She leaned towards the speaker as “My First Knife” wept like sour, oily smoke from out of the device, and as her posture shuffled from degrees of earnest, straining focus to full-body, waspish scowl I began to marvel at how different the music sounded there with her than it had just a few hours earlier. It was aggravating, like a loose tailpipe dragged shrieking over pavement. It was an utterly disagreeable waft of sour milk. There in that moment it was way the fuck unwelcome.

And yet it was precisely the same music I’d been ravenously absorbing for days now, absolutely savoring its ‘aggravating’ glory. Obviously, it was the receiver that had been altered, the transmitter was no more or less flawed than ever before. I was interpreting it all differently. And so, the question surfaced from wherever it is that questions bubble up from: what does Today Is the Day really sound like divorced from all of our petty biases? Can music even be evaluated outside the vacuum of lived experience? Can melody have any sort of value in that sphere? And what about the flip side? Is it possible to measure music’s value when passed through the lens of very specific biases?

“I’m sorry but I think this is going completely over my head,” sighed my exasperated coworker inching farther back into the streetlamp’s ghastly sherbet-colored corona.

For example, I thought: what would Today Is the Day sound like to a career musician who’s suffered overt bodily trauma, who’s physical pain’s advanced enough so that they can barely hold a guitar pick between their fingers anymore? A musician who’s travelled so far inwards that they encode their latest album with cryptic personal asides to the extent that the album’s subtext is essentially impenetrable to everyone but themselves; like cairns raised along an overgrown path leading back into the past?

“Huh?” I startled, pressing stop. “Oh yeah. Well, the track was almost over anyway.”

I was absent; lost within the hedge-maze of this specific thought: What does Today Is the Day actually sound like to Steve Austin?

“The crucial discovery was made that, in order to become painting, the universe seen by the artist had to become a private one created by himself.” —André Malraux

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE?

“I feel like anytime ever that I’ve listened to music that was doing something different than what everyone else was doing, it usually turned me off. It usually made me go, ‘what the fuck is this?’ It could take me two weeks to a month for it to set in my head ‘till finally I would go, ‘Oh my god… this is totally doing something for me that I would have never expected from a heavy, underground music album.’”

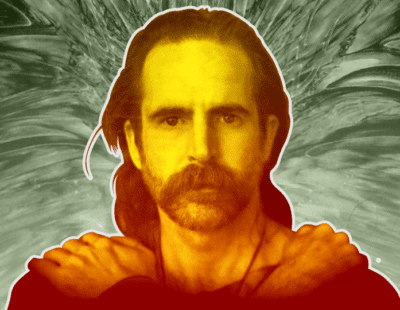

Steve Austin’s voice furls outwards like wisteria over abandoned power lines. It moves at its own pace, curling in and around itself in strange paraphrastic arcs, swallowing up whatever talking point the interviewer may have dispensed and utterly reshaping the ground beneath it. It’s easy to become boxed in or else turned contrariwise by one trajectory as it cooly forks into multitudes. You’d best have brought along a map.

“Look, whenever you break the flow of anything and you try to do something different, you’re going to have to be brave enough and believe enough in what you’re doing,” he continues. “You’re not Led Zeppelin, this is not going to be an instant crowd pleaser. And whatever; I’ve always tried to ensure that Today Is the Day is the opposite of the mainstream, meaning that there’s no ‘prepared statement,’ there’s no preconceived ideas. Everything is free-thinking stream of consciousness that’s put out there as just this very visceral testimony. This is not a party experience.”

As a piece, No Good to Anyone may be a lot of things. It’s a deafening salvo clattering the earth in the wake of a protracted dead zone, it’s an annotation on the sinew of human will, a type of musculature so few of us ever deign to exercise, it’s the ominous rattle of a coyote testing its strength against a length of chicken wire. However, what No Good to Anyone is not is a ‘party experience.’ There are moments on the album that can feel at best like daunting incidentals and at worst like small scale catastrophes akin to watching a musician being sucked downwards into wet earth as they stubbornly push onwards through the show. It can sound like a machine vomiting sparks as something essential ricochets loose around inside it. And it can certainly effect, a kind of awesome magnetism on the listener as it rears back off the heels of its foundations while refusing to give in and topple. But one is rarely moved to celebrate in a storm cellar, (especially not to the tune of the structure’s groans of torment above them.) This is not a party album. This is not Led Zeppelin.

“Yeah well the whole point of the album is to go right over your head. Anything that breaks the mold is going to find resistance initially but I don’t think you can make great art if you’re afraid to do things that are untried and untested. I make these records to try to understand life. They’re a healing tool. I try to make something that—during whatever period of my life—behave like a little mirror that I can study my reflection by and try to understand what exactly is happening to me. Throughout all the albums up through this one, I feel like I’ve always been seeking answers and I’ve always been trying to understand myself because I don’t understand myself a lot of the time.” Steve loiters over the thought like cigarette smoke just outside an office break-room window. “I have a lot of built-up, super-intense anger that drives me fucking crazy but then at the same time, I’m the most loving, caring, thoughtful person. And it comes from the heart,” he emphasizes. You know, this whole time that I’ve been doing Today is the Day, a lot of it has been about exploring a question. It’s been trying to understand what it means to be a good person in a really fucked up world, trying to come to grips with the fact that you’re not always a good person. Sometimes you’re a bad person. Sometimes you’re a villain.”

NONE OF THE SHEEP WILL SURVIVE

“All art is a revolt against man’s fate.” —André Malraux

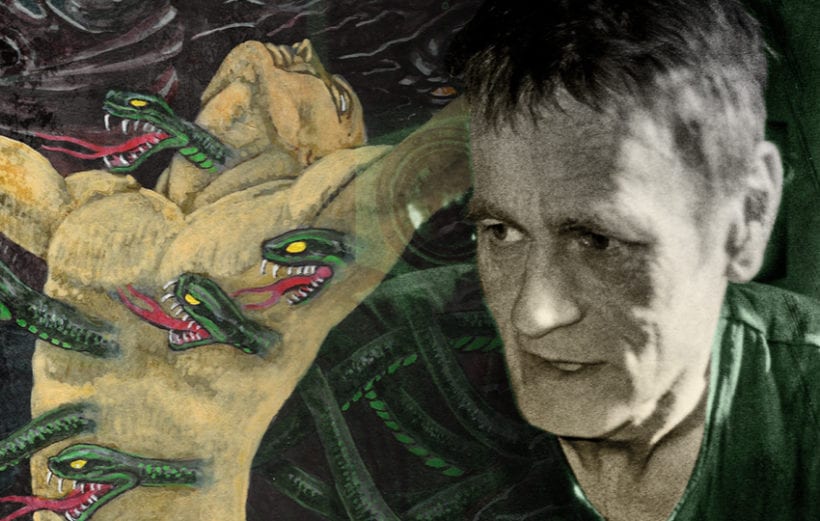

Researchers from John Hopkins Hospital have estimated that as many as 40-80% of chronic pain patients are routinely misdiagnosed owing most especially to the physician’s failure to take a comprehensive history from the patient and from ordering the wrong tests. Following a van accident in 2014 in which Today is the Day’s touring vehicle was struck and flipped upside down across l-495 at 65 miles per hour, Steve Austin began to suffer severe and persistent inflammation and found it increasingly difficult to walk. His condition was diagnosed as one of any number of things “from rheumatoid arthritis to fibromyalgia.” On the counsel of one physician and desperate for relief, Austin began rounds of an intensive anti-convulsive medication.

Now, let’s say that this specific proscription had been determined correctly. Anti-convulsive medications function by altering electrical activity in neurons or chemical transmissions between neurons. From there the potential cascade of side effects are as aggregate and as variegated as one can imagine, but—according to the medical resource site RxList—one of the most common side-effects across all of the most commonly prescribed seizure medications is the inducement “of suicidal thoughts and action,” (not to mention such possible delights as liver failure, serious blood disorders and—perhaps paradoxically—violent tremors.) Even in the best case scenario things can get dicey. Now imagine a body increasingly consumed by agonizing fits of inflammation, whose throat can swell up to the extent that its airway’s can become fundamentally blocked, whose hands and face might expand to twice their size and begin to feel as if they’ve literally been set on fire. The pain is fucking exquisite and the body can become physically unrecognizable to its owner. Imagine this drug and its potentially deadly psychological effects being introduced to this system, (entirely based on a misdiagnosis, mind you,) and the unholy chaos that can ensue from there. Just think about it for a second.

Still feel like you’re having a fucking bad day?

“If this album were a film, then when ‘Attacked by an Angel’ kicks in it would have been like shifting all of a sudden from this dense action scene with the first track to a shot of a hospital patient who is heavily drugged, staring out the window trying to cope with pain, fantasizing in terms of trying to reconcile their previous life with being immobile, ‘Sit and watch the time go by of which I am a slave, all the time that’s rolling by I cannot ever save,’” Austin sings soothingly. “This is just me staring out the window, daydreaming. Just trying to understand what’s happening to me.”

Let’s just say that my introduction to No Good to Anyone got off on the wrong foot and “Attacked by an Angel” was the proverbial out-of-kilter cadet that fucked up the entire military parade for me. I hated it. Its slippery, rhythmic nonchalance along with those coequally detached modal shifts in Austin’s vocal delivery, (contrast the melodic phrasing between the second line of the first verse and its reprisal on the second verse,) irritated me to the extent that I was initially closed to the album and began forecasting my sure-to-be high-minded and punishing review with genuine relish. But as it often happens with a new crush, it was this same track that took to roosting in my thoughts during the oddest moments, first as an interloper and then as a welcomed guest. Upon inspection “Attacked by an Angel’s” blemishes began to look a lot more like beauty marks such that I became enthralled by its eccentricities; until even -let the record show- I came to adore that subtle modal shift in the second verse, (“there’s no hope for you or I, you’re guilty and betrayed.”) And with that single but noteworthy recalibration the entire album clicked sharply into focus. Ah, this song, man… It lurches like an old whale-boat drawn into the eye of a ferocious squall. You can almost feel your grip slowly loosening from the mast as the waves salivate beneath the soles of your feet.

“It’s funny because I had this riff that I kept playing around with on tour,” Steve’s smile telescopes out from the compressed wave issuing from my laptop’s speakers into something nearly tangible. “It’s five notes and it repeats in a weird way and I don’t know why but I just kept grabbing that riff 1-2-3-4-5, 1-2-3-4-5, 1-2-3-4-5. It was very monotonous but it was also extremely difficult in a very weird way to play. The fucking thing should be so simple for someone like me who’s been playing odd time signatures my whole life so I don’t know why but when I went to record that fucking part it was a trip to do,” he laughs. “And when I got through making that song—just as a fan of hard music and whatever—I listened to it and I thought, ‘Steve, what are you even doing?! What is this vocal style at the front end?’ But I realized that for me to do it the right way, it needed to not be sung powerfully. It had to come from a fragile place to where you’ve just got the breath to push it out, almost like you’re muttering to yourself rather than you’re speaking to someone else. And you know, one of my favorite parts on the whole album—that I think is pretty fucking inventive—is the ending of ‘Attacked by an Angel.” It has this almost Meshuggah-like, mechanical, industrial rhythm… its off time again so it fucks you up when it kicks in but there’s also the vocal I laid down there. I sang it in a Southern accent—like cowboy style—so that, (hopefully,) it would accurately reflect me as a person or as a spirit. Like my spirit singing on top of this mountain near my house and my ashes being scattered from it by my family.

“Now that I really think about it, this album’s fractured-ness probably is a good capture of what my life was like around then because very little of it made sense. It was just fragments, you know? One minute I was dreaming about something just thinking these really morbid thoughts like ‘am I going to cut my arm off? What am I willing to do to end this pain?’ but then the whole fantasy shifts… Like, now there’s a birthday party and I’m using a walker to make it into the kitchen to sing happy birthday for my son. So [the record is] all of these different little fragments collected together like a family snapshot album and yeah, it’s definitely weird. But it’s a pretty good diary. I would think that if my son Hank had a kid one day and he was wanting for him to understand his grandfather at this period of time, if he was to put on this album for him, I wouldn’t doubt that the kid would listen to it and go, ‘Oh, okay, I kind of have a picture of what grandpa was doing. I can sort of see who he was.’”

“The greatest mystery is not that we have been flung at random between the profusion of matter and of the stars, but that within this prison we can draw from ourselves images powerful enough to deny our nothingness.” —André Malraux

WUNDERKAMMERN

Richard Feynman was a theoretical physicist who proposed that all positrons are merely electrons that are moving backwards through time. It’s worth noting that he didn’t seem especially fond of this idea because he didn’t care for many of its implications. Nonetheless, it was simply the way the math worked out ergo that’s the way this particular slice of cornbread crumbled. Think about a black hole, a region of arching spacetime fringed by an event horizon and broadcasting a jet of positrons in the form of antimatter. According to NASA, when a star’s enthralled by the gravitational pull of a black hole it begins to collapse in upon itself. But as the star is drawn closer to the black hole’s theoretical boundary—the event horizon—time slows down and then finally…stops altogether. The star is no longer collapsing while it is now simultaneously always collapsing. It’s like being torn apart by the past while being held in stasis by the present.

If you could gaze into the past, what would you really see? Would it settle into familiar forms before you? When the Greek statues of pre antiquity arrived to European museums of the 18th Century, they came bleached by time of all their color. And therefore, ever since we’ve collectively envisioned an Ancient Greece populated with either alabaster or drab, khaki-toned statuary. But according to Plato these statues were actually painted so realistically that passing birds were attracted by the clusters of grapes that they held. All except for their eyes. Plato said that their eyes were customarily painted red; imagine that!

Maybe our past is nothing like we left it. Maybe the past stares back at us through blood-red eyes.

We’ll close the loop on the first portion of this observation here. Of course, we’re by no means done. If you thought that Steve Austin might simply have nothing more to say then you don’t know Steve Austin. Which, my friend, you most certainly don’t.

“What is not surrounded by uncertainty cannot be truth.” —Richard Feynman