Suzi Quatro is shouting at me. Even though she’s calling on the phone from England and an ocean separates us, the queen of rock n roll is so worked up, her words all but punch me in the side of my head.

“I am most proud that I stuck to me and made it on my terms!” she yells in a raspy voice. “Nobody else’s! You see how passionate I’m getting about it now?”

“I do. That’s your selfness,” I say to the one person who has arguably done more to kick holes in hard rock’s glass ceiling than anyone in history.

“It is,” Quatro affirms. “And at the end of your days, when you’re lying six feet under, you can say, ‘I did that.’”

There’s not much Suzi Quatro hasn’t done. At age 68, she is a living legend, hyperbole be damned. Yes, there were women who played instruments prior to her, but she was the very first bona fide rock star among them. The pride of Detroit Rock City, Quatro had her life gloriously upended as a little kid when she watched Elvis perform on TV. In a flash, she saw her destiny. Years later, when a young Joan Jett saw Quatro, Jett saw her own destiny. And so on and so forth.

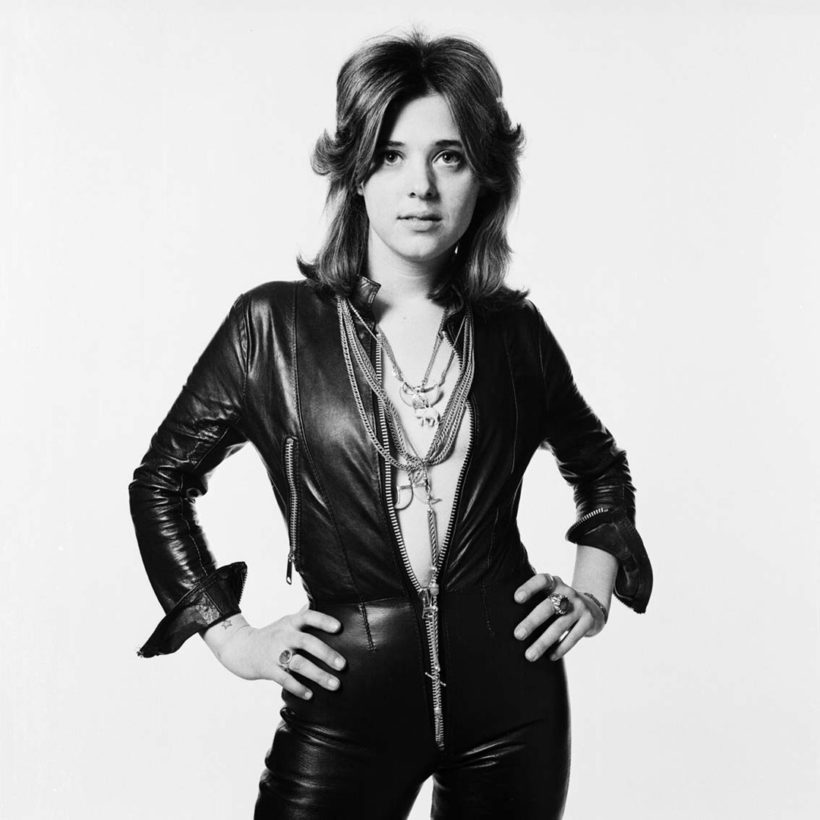

As a young teenager in the ’60s, Quatro sang and played bass with her sisters in the garage group the Pleasure Seekers (later Cradle), hitting the hard rock circuit alongside their contemporaries the Stooges and the MC5. But it was when producer Mickie Most brought her to England in 1971 that Quatro flourished. With formidable bass-playing prowess, headbanging performances and a now-iconic black leather catsuit, she had a string of snarling, rollicking hits: “Can the Can,” “48 Crash,” “Daytona Demon” and “Devil Gate Drive” among them—though American audiences probably best know Quatro from her stint as the bad-ass Leather Tuscadero on Happy Days in the late ’70s.

Over the course of a five-decade-long career, Quatro has released more than 15 albums. The latest, No Control, was written mostly in collaboration with her son Richard Tuckey and is scheduled for a March 29 on SVP/Steamhammer. She recently spoke with Decibel about being a reluctant sex symbol, bypassing gender and crying during children’s movies.

The themes of staying true to yourself and not being manipulated are all over No Control. What is it about that message that is so significant for you?

It’s kind of been my mantra my whole life. I’ve always felt that all you’ve got in life is you. You’re born alone, you die alone. If you collapse into someone else, professionally or in a relationship, you’re gone. Who are you? And I’ve always tried to stay exactly who I am, through hell or high water. Do not try to manipulate me. Mickie Most once said to me, “Suzi, you are not somebody that anybody can tell what to do. I can suggest, and that’s it.” And I thought, “Yeah, that’s pretty much it.” But I’m not stubborn. If I hear sense in something, I’ll take it and put it around my head. At the end of the day, and I said it my whole life, I can not be anybody else but me. I can’t do it. Rough edges and all. This. Is. Me. If you don’t like it, fuck off.

What did Detroit teach you during those early years in the Pleasure Seekers and Cradle that you would carry with you throughout your career?

It gave me a strength; Detroit people are strong. It gave me an energy level that is second to none. It gave me an edge. Detroit lives on the edge, that’s the main thing. I’m on the edge all the time. Detroit is in you from the day you’re born ’til the day you die. Even though I’ve been in England for a long time, my box set, released in 2014 to celebrate then 50 years in music, which is now 55 years, was called The Girl from Detroit City. And that’s me. It was one of the best cities ever to grow up in. When I go back there, I still, I just—oh, God—I OD on the city.

The album cover for No Control is just you in your black leather with your bass slung across you—it moved me, really. I thought about how many people must’ve looked at Suzi Quatro over the years and had the same life-altering reaction that you did when you saw Elvis for the first time. So image in rock ‘n’ roll is obviously important. Were you consciously making a statement with your style when you were starting out?

Let’s go right back to the start. When “Can the Can” was recorded, it felt like a number one. At that point, everything was making sense. Mickie said to me, “We need to do a professional photo session. What do you want to wear?” Now the image comes. I said, “Leather.” He said, “Noooo.” I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Nooo, it’s been done.” And I said, “Not by me.” I was an Elvis fan. To his credit, Mickie said, “Ok, you can wear leather. What about a jumpsuit?” I said, “Great idea.” I swear to God—may the roof cave in on me—I didn’t know it was gonna be sexy. I didn’t know it! I thought a jumpsuit was a sensible idea and everything would stay put. Then I saw the pictures, and I went, “Ohhhh.” [laughs]. I never do things thinking it through, I just do what comes natural. But what a lucky thing that was because it’s an image that’s timeless and that’s stayed with me my whole career.

You created an iconic look by accident.

That’s the other part of the story. When we went into the studio to do the first proper photo session, I was standing there in front of this great photographer, got my jumpsuit on for the first time, my record was playing in the background on the speakers, the boys [in my band] were draped around my legs—I always remember this, it’s a pivotal moment—the photographer said, “OK, give me that Suzi Quatro look.” I didn’t know I had one. But all of a sudden, I did. Do you get that?

Uh-huh.

I went voomp, and there I was.

It’s just so funny to me that your sexiness was a surprise to you. I learned you’re rather modest when it comes to talking about your sex symbol status.

Yeah, I am.

The irony…people associate rock n roll and rock stars with sexual energy.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’m always getting told by people about the posters [of me] they had on their wall, and it embarrasses me because you don’t see yourself that way. But I take it very much as a compliment—thank you very much that you found me attractive—but I don’t take it seriously in my heart. I mean, the worst part—and I get it all the time, all the time—guys will say, “Hey, I had your poster on my wall.” OK, thank you. “And you know what?” Yes, I know what, I don’t need to hear it. And they want to share the details! Thank you! I get the picture! I think they were thinking, “Well, you were there!” [laughs] I don’t have any problem talking about my artistry, but I’m a little bit shy about looks. It’s funny. I didn’t grow up that way, and I was a little bit of a tomboy. You know it’s nice, but… oh, I’m embarrassed again!

You played Reading in 1983 with Black Sabbath and Thin Lizzy. Do you feel a kinship with metal bands and audiences?

I’ve got enough heaviness in what I do. It edges a little bit more toward rock than metal. I loved Thin Lizzy, they were friends of mine. Loved Deep Purple, loved Black Sabbath, they’re all good acts. I even love Guns N’ Roses. I do! I love “Knockin on Heaven’s Door,” that’s my favorite.

There are many adjectives that come to mind when I think about Suzi Quatro, but the first one is cool.

Ok, I can accept that one. (laughs)

So tell me, what is the most uncool thing about you?

Oh my God. There are so many uncool things. I’m soft and vulnerable on the other side. I cry over things like Toy Story. That is definitely uncool. I was watching Toy Story with one of my grandkids, he’s only about 8, and I started to cry, and he looked at me—and he is 8!—and said, “Grandma, why are you crying?” And I said, “Shhh!” It was when the toys were going away! Very uncool.

You’ve been in the music business since you were a teenager. Of all the challenges you’ve faced in your career, which are the ones you are most proud to have fought to overcome?

Oh my gosh, there are so many. So many. The main one is probably when I got plucked out of the band [Cradle] and taken to England. I had no money, I was living in a tiny little room, my family was in Detroit, my band was gone. I had my bass guitar, my record contract and that was it. I used to sit there at night and cry myself to sleep. I used to think in my darker moments, “Oh God, this person you want to be, this bass player, this rocker… maybe you just need to be a little bit more like Melanie or Lulu or Grace Slick.” In the end, I came back to the same place every time: No. Whatever it is, this is me. I know it hasn’t been done yet, but whatever this is, if I don’t make it as this person, I might as well not make it at all. And that’s what I’m most proud of: I stuck with me. I did not have a blueprint. There were no girls before me playing a bass guitar. I couldn’t say, “Oh, I wanna do what she did.” All the girls after me, they could point to me and say, “She did that, and that’s what we wanna do.” Great! Great. We all need a starting point. But I didn’t have a starting point; I was the starting point.

Were you conscious your potential to influence future generations of rockers, especially women?

On some level, I was just being who I was. I didn’t think of myself as a female musician, I still don’t. But then as I started to be successful, people were throwing this at me: “Do you realize you’re the first?” I didn’t know it, but as the world goes, this had to happen eventually. In hindsight, at the grand ol’ age of 68, I think the reason it fell on my shoulders to be the first to do this is because I actually don’t do gender. I think the girl to open the door had to be almost asexual. I’ve had this conversation with lots of famous musicians sitting at the bar after a show. All guys. I asked if they thought of me as a girl bass player. “No, we didn’t.” I asked if they thought I was out there being sexy. “You were, but you weren’t trying to be.” Right, so what was I? “We don’t know. You were just this natural entity doing what you do.” This had to be the thing to open the doors—it couldn’t be a girl being a girl—it had to be a girl who actually did have her feet in both camps without thinking about it. But I couldn’t have said that at the time. I stuck to me. Whatever I was, I was the unique thing to make this happen and open the doors. Somebody had to do it and it fell to me and I’m so glad I did.