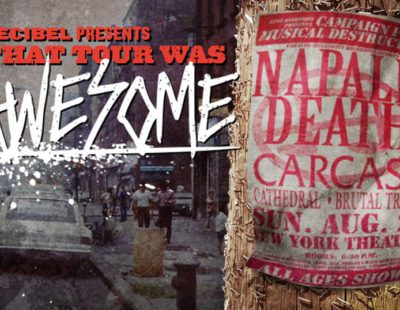

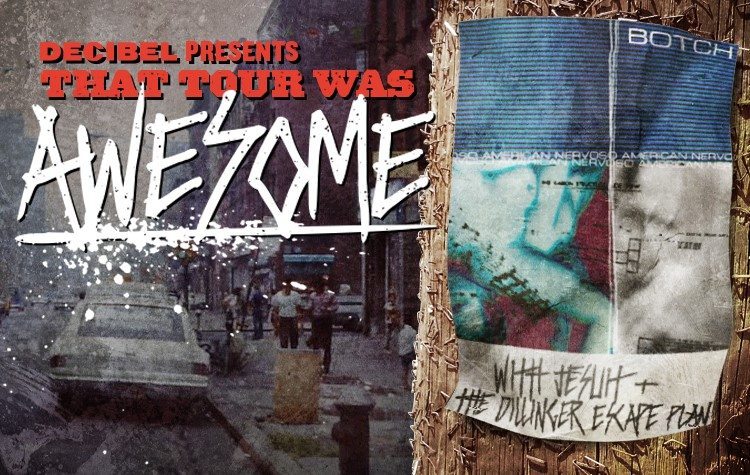

For this installment of “That Tour Was Awesome” we’re going to submit for your consideration a tour that was as awesome as it was not-so-awesome. Looking at that line-up through a twenty-year-old lens, it certainly appears to have been a bill that would have forked your eyeballs and ears out with extreme prejudice. You had the burgeoning calamitous complexity of a pre-We Are the Romans Botch taking the “evil math rock” of their American Nervoso debut to the streets (and let’s not forget those mainstays of the ‘90s hardcore live show: halogen lamps and strobe lights). There was Richmond’s Jesuit whose music swayed from challenging cantankerousness to sarcastic slamming. Opening the nightly proceedings was the then-virtually unknown Dillinger Escape Plan who, at that point, still had ink drying on their first deal with Relapse, hadn’t even released Under the Running Board and were excited to be on their first tour.

And if you caught the opportunity to witness this full package, you were one of very few. Dillinger only ended up doing the first portion of the tour, Jesuit missed a few Canadian dates at the hand of border and van trouble and Botch’s ailing transport forced them off the last leg of the tour. As well, despite the “Holy Shit!” factor this line-up generates today, one has to remember the extreme music scene was a vastly different animal in 1998 and this tour was actually a very small scale, bare bones outing. Still, it was significant for a number of reasons: it was DEP’s first foray into what would become the next twenty years of their lives and somewhat of a coming out party (yours truly witnessed them in the basement of a Toronto record store during which they immediately became my one of my favourite bands and I made it a mission of sorts to spread the word), it saw the dissolution of Jesuit soon after and the drafting of guitarist/vocalist Nate Newton into Converge (as bassist) and guitarist Brain Benoit into Dillinger, it stoked tensions within the Botch ranks that contributed to their We Are the Romans opus a year or so later and had dudes come to the realisation that on-tour pranking may be fun, but is ultimately demoralising. On the flipside, however, there are a shit load of awesome tales to tell, so we gathered Nate Newton, Botch bassist Brian Cook (now in Russian Circles) and Dillinger guitarist and lone original member, Ben Weinman to reminisce about sweaty basements, van caravans and shit in cups.

Botch’s homemade light show. Home Depot has never seen work lamps sell as well as they did in the ’90s.

Botch’s homemade light show. Home Depot has never seen work lamps sell as well as they did in the ’90s.

OK, let’s start off by examining where you felt each of your bands was at at the time. Looking back, what was your intent and what had you hoped to achieve on this tour?

Nate Newton: I felt like we were pretty unhappy with where hardcore was. I felt that hardcore in the mid-to-late ‘90s was really stagnant, kind of boring and we just wanted to start a band to scare people and all that. It sounds pretty egotistical to say now, but that was it, as silly as it sounds. I remember the feeling I had when I was young and going to shows of danger where you didn’t know if the crowd or the band would beat you up or bite you or something. I just wanted to make a band that kind of made me feel like that again. I know this is sounding totally dumb now and it’s a “great” description, but at that point Jesuit was a really reactionary band and everything we did was a response to things that were happening at the time in addition to wanting to write punishing heavy music.

Brian Cook: I think we were all really excited. It was one of those things where we were playing last, but I hesitate to say we were headlining. We were playing last, but I think us and Jesuit were on equally footing, but we had an album coming out so we were like, “we’ll play last.” It was the first tour we had done that wasn’t booked by someone in the band. It was done by Matt Pike who’s at the Kenmore Agency now, not Matt Pike from High on Fire [laughter]. There were guarantees for a couple of the shows for like $100 and that was amazing to us. A lot of shows up to then were a tip jar/donation/pass the hat around kind of thing. There was a lot of excitement because it seemed like it was going to be more of a legit thing than we had done in the past. On our previous tour we had out with Ink & Dagger on a seven-week tour of the states. That was our first tour and, still to this day, one of my favourite experiences in being in a band. It was our first US tour and everything went really well and I think there was an expectation that this was going to be even bigger and better, even though it didn’t wind up that way.

Ben Weinman: Dillinger had no camaraderie with anyone at that point. That was the first time we were making friends with people or sticking together on a tour. We had no friends up to that point; we were an island. We weren’t part of a scene, nobody in our band had been in some other band that anyone cared about, nobody in our band ran some cool label, nobody in our band did a cool ‘zine. That was our first legit tour. Before that, our version of touring was to get on whatever message board there was and find the kids who did shows wherever and try to put together two or three weeks of shows and it’d be like a show, three days off, a show, stay at some kids’ house for two days, another show. So, this was our first real booked tour, our first coming out.

How did the tour come about?

Newton: Botch and Jesuit became friends pretty early on. Both bands met on our first tours. We played in a basement together in Madison, WI, I think. Right away we became kindred spirits, we dug each other’s bands and sensed we were into the same things and about the same things and immediately, it was like, “we gotta go on tour together.” And I think that was a goal we both set pretty early on.

Cook: We had played with Jesuit two or three times on our first east coast tour in the summer of 1996. Jesuit had been out with Converge and we played with them in Virginia Beach and I think Milwaukee and we had stayed with Nate in Virginia Beach. We knew Nate pretty well and we knew the band and they had come through the summer of ’97 when they did a west coast tour with Piebald and Harkonen and I think I put them up in Tacoma. We had a friendship going and we talked about touring together at some point in time. Dillinger, we didn’t know at all. They were on the first half of the tour at the suggestion of the Jesuit guys. I hadn’t even heard of them at that point, but they were excited about them. The arrangement was that they were going to do the first part of that tour and we picked a Seattle band called Jough Dawn Baker to do the dates from Seattle to the end of the tour.

Weinman: We had put out our first EP, the first self-titled Dillinger EP and were able to do some minor touring and shows around that, but it was pretty scattered throughout the east coast. We wrote and recorded Under the Running Board before signing to Relapse. We started playing it around for people, sending it to friends and it got to Nate and he was pretty blown away and super into it. He was a serious wise-ass, had no problem with being honest and was like, “whoa, this is actually pretty good.” He was like, “we’re going on tour with Botch, you guys should do it.” I think that was the first seed. At that point, Botch didn’t even know who we were and hadn’t ever heard of us. They were just like, “yeah, sure. Whatever.”

Brian Cook

Brian Cook

Obviously, the infrastructure and touring circuit was a lot different back then where most shows and tours were done via DIY booking. Was this the first tour you did through a booking agent?

Newton: Yes, it actually had a booking agent behind it. It’s tough to say, but I wanna say Matt Pike booked it. Matt still books Converge now and he had just started booking tours. Maybe it was a collaboration between him and whoever Botch had on their end. What was interesting was that it was coming out of a time where there wasn’t an infrastructure in that world. It seems like in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s there were booking agents who specialized in hardcore and it was easier for certain bands to get shows in clubs and stuff, but it all sort of died in the early ‘90s. It seemed like our little world started getting shit going again. So, right around the time you had Hydra Head, Reservoir Records and all the bands associated with them, you also had people start booking shows and trying to book tours.

Cook: It was a gradual step. Matt Pike agreed to book the tour, not on a commission, but he was just starting. He was friends with Aaron Turner at Hydra Head and Hydra Head’s whole thing was to let Matt books these tours. I think the arrangement Aaron and Matt had was that Aaron gave him a painting in exchange for booking the tour. It was all really casual and a continuation of what we had done in the past, I guess the expectations were bigger.

Was there a noticeable difference having a tour booked by someone else?

Newton: There was still a good share of uncertainty happening on that particular tour. I specifically remember situations where we didn’t know if there was a show happening and there were other times where there was a show, there just wasn’t any people there.

Weinman: It was pretty early stages for everybody on that tour. We were just playing basements mostly and a lot of VFW halls and small punk venues. It was very conservative, in hindsight, but for us it was awesome because somebody in the scene – a new, young dude who books shows – was actually putting it together. That was huge for us. It was crazy. Me and my friend [former DEP manager] Tom [Apostolopolous] had done so much work up to that point in booking shows and getting our name out there as best we could, the fact that someone sent us an email with organized dates and Mapquest routes was insane.

How long did the tour run?

Newton: I want to say it was close to two months. And that summer I had gone on my first tour with Converge, came back and went right back out with Jesuit. So I remember being gone for-fucking-ever that summer. Maybe in my mind it was two months long and maybe it was only a month, but it seemed like it was years.

Weinman: We didn’t do the whole tour. We broke off after a couple weeks in Richmond, VA. I’m pretty sure they both played shows to get out to the first show. We did a couple weeks together, which to us was the longest tour we’d ever done and we broke off to go play the Milwaukee Metalfest.

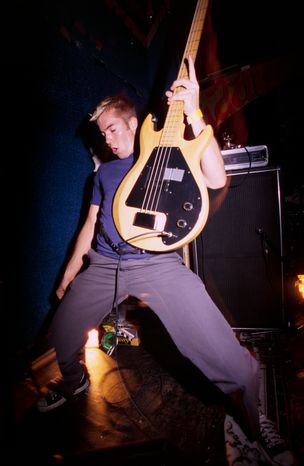

A young DEP, in shorts!!

A young DEP, in shorts!!

Where did it start?

Newton: I think it was in Columbus, OH, maybe Dayton, and we might have played a show or two on our own on the way out there to meet the tour. We played in a basement and it was the first time any of us had seen the Dillinger Escape Plan and it was the first time Dillinger had ever toured. Also on that same show, I want to say Milhouse and Silent Majority played. I specifically remember that show because all I had from Dillinger at that time was an unreleased tape of Under the Running Board. Tom, who was their friend/manager at the time, had done some shows for us in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, so he gave me a tape to check out. I was like “holy shit! These guys actually know how to play their instruments!” They were actually my suggestion for the tour. I remember standing with Dave Knudson right when Dillinger started playing and they just immediately…they weren’t even playing. They were just throwing their guitars at people, trying to stab people with their headstocks and going nuts. I remember just looking at Dave and Dave looking at me and Dave saying, “what the fuck are they doing?”

Cook: I actually kept and found a tour diary that I re-read this morning, so I don’t remember this happening, but apparently it happened: supposedly, we had a show in Lawrence, KS that was supposed to be at a house, but the house burned down, so it got moved to another house that was like a crust punk house that was having a college kegger. People were setting off fireworks in the show room while we were playing and there were passed out drunk punks everywhere. So that was our first show. The only other thing I remember is that this band Wormwood played and they ended up eventually moving to Seattle; that was the first time I met them. Then we played one other show on the way out before we got to Columbus. That first show was us, Dillinger and Jesuit as well as Indecision, Silent Majority and Milhouse. It was a six band bill in the basement of a house owned by the guys in this band Inept and I think it’d be generous to say there were 30 people who paid to see the show. That was our first time seeing and meeting Dillinger and I think this is well-known at this point, but our initial impression of them wasn’t favourable [laughter]. I don’t think it was a great show for anyone though; it was just this hot, crowded basement. It didn’t seem like there were any discernible parts, it was just them attacking the audience. It was like, “what is this shit?” You can go crazy and make a racket, but headstocks were getting dangerously close to people’s heads and I remember being weirded out by that and concerned for the safety of these girls who were there. Then Jesuit played and I think [vocals/bass] Brett [Matthews] blew up his cabinet and I don’t even know if they played a full set and I don’t remember what happened when we played. Five of the six bands stayed at the house, Dillinger took off because I think they got the vibe that we were bummed. And that was the first show.

Weinman: The first show was Columbus and it was in a basement of something, I don’t know if it was a frathouse or something, but it was something weird. Specifically, I remember some of the guys from Botch watching us play first and there was no stage, a few kids just sitting around and most of the people were not down there while we were playing. Most people were hanging out in the driveway; we could see their feet from the basement window. We started doing our thing, running around, going crazy, running head first into walls and people, knocking shit over and I remember Dave Knudson looking at us like, ‘what the fuck is this?’ Like it was the biggest bunch of garbage, noise, monkey show he’d ever seen. I remember him being so annoyed, not even unimpressed, just annoyed. It was like we were invading his space, rolling around on the dirty floor near his shoes or something. I remember him and whoever else he was watching with just walking out. And the looks they had on their faces…it was like somebody just took a dump right in front of them; that was the look on their faces.

Some of you knew each other, some of you didn’t. What was the initial social vibe like?

Newton: I remember it being pretty good right away. [Ex-DEP vocalist] Dimitri [Minikakis] and [ex-bassist] Adam [Doll] are very affable people and easy to get along with. Ben is super-outgoing and right away he was making friends with everybody. [Ex-drummer] Chris [Pennie] was pretty quiet and kept to himself at first, but was a nice guy and their other guitarist at the time, John Fulton, was a nice dude, but I remember him having this sort of human robot vibe. I think they used to call him “Fultron” or something. Everyone hit it off right away and as the tour went on, everyone got along. I don’t think there was any weirdness or anything like that between anybody.

Cook: I think the next night was in Kalamazoo and [when Dillinger played] it was like, “oh wow, these guys are awesome!” It was literally the first show and not knowing how we felt about it, but the next show it was like, “these guys are all right.” Good people, good band and the vibe totally improved after that.

Weinman: We had met some of the Jesuit guys before, but we were definitely the newcomers. It was like these guys are friends and we were just kind of rolling up and there was a little bit of a hazing going on. They already had their inside jokes and everything. But I think it was like most times when you have people who listen to Dillinger, or end up liking Dillinger, it’s a lot to take at once, it’s a lot of sensory overload and it’s not something you can necessarily absorb right away. I also have a clear memory of, after the first show, Nate going into Botch’s van and playing them a tape of Under the Running Board, saying “you gotta check this out. Seriously, they’re legit.” They listened to it and having a similar reaction that a lot of people have; that it’s just next-level crazy, it’s going off and ‘where did you guys come from?’ The reaction a lot of time was like it was alien shit and to me it was amazing that our music was doing that to people, including people who were amazing musicians who weren’t afraid of aggressive stuff, even those guys who were in some of my favourite bands were kind of mind-blown by it. Our first EP was a first taste of us figuring out what we want to be and where we were going, but Under the Running Board solidified who we would be. I guess those guys were the first critics we had for that stuff.

I personally saw the Toronto stop of that tour in the basement of a record store. Were the venues mostly along those lines: a lot of basements, record stores, VFW halls, coffee shops?

Newton: There was a lot of that. There were some club shows. There were DIY space shows, some firehalls and lodges and shit like that, but I’m drawing a blank on a lot of that stuff. Most of that tour was us and Botch doing the full US and that was the tour where we got detained at the border and missed all the Canadian shows except for Montreal which was the last one. I can’t tell you about any of the other Canadian venues.

Cook: They weren’t great. That was the thing that was the harsh reality of that tour. There were definitely good shows, but in general I think we were all kind of surprised because we had anticipated it was going to be bigger and better than the tour before that had been booked by someone who had a reputation for booking things, we were a bit bigger, Dillinger was on Relapse and Hydra Head was becoming a thing. I think our expectations weren’t crazy high, I just think we were expecting it to be better than the tour we’d done before and it wasn’t. I’m not sure if it was because the previous tour was in the spring and we were competing with fewer tours and shows in the spring than in the summer. Every town we played it seemed like there were three other hardcore shows going on, if not that night, at least that week. That was the era when everyone was in bands while simultaneously being in college so everyone toured in the summer and I think it was the wrong time for us to go out. For the most part the shows were in basements and VFW halls and there were a few real clubs. It was a really awkward tour because I think we were excited to get out of playing house shows and sleeping in the same basement we just finished playing in. It was like, “oh, we can play clubs and maybe get a hotel afterwards.” I think I was still excited about the whole DIY hardcore aspect of things whereas the rest of the band was ready to move on. So I think there was some tension there because we’d have a shitty show and the response would be, “well, let’s get the fuck out of this place and go get a room.” But I was so broke that I didn’t want to spend $60 on a Motel 6 when we could have crashed somewhere else. I was living off of no money, so I was pretty desperate to keep things as economical as possible.

Former Dillinger dudes Chris Pennie and Adam Doll

Former Dillinger dudes Chris Pennie and Adam Doll

I understand pranking and van wars were a big thing on this tour.

Weinman: We all were in vans, obviously, but Jesuit and Botch were having these van wars. We’d be caravanning down the highway and they would be shooting fireworks at each other’s vans. We were just like, ‘what the fuck is going?’ We were our own thing and those guys were obviously close friends from beforehand and they were shooting bottle rockets and throwing eggs at each other’s vans and we didn’t understand that. But, I think what we learned most on that tour was about healthy competition. Before that, we didn’t give a fuck about anybody, every band needed to be destroyed. It was like, “fuck everyone!” When we met those guys, we ended up being so close and realised that we had so much in common that it was cool to respect a band and see them as someone who makes you want to do better, not just “fuck them.” You want them to do well, but it inspires you to do better and go farther and I think we all had that for one another. We watched each other every night and eventually respected each other’s strong points and differences. At the same time, I remember we were coming through the Canadian border, going back in and one of them was parked at the side of the road as the other passed and they just bombarded the other’s van with like 100 eggs. We got hit as well and I remember Chris, our drummer who owned the van, just losing his mind. He was so pissed.

What about Jesuit’s adventure at the Canadian border? What’s the story there?

Newton: The story is that we’re fucking idiots [laughter]. Back then, “promoters” didn’t want to do anything legitimately. It was always the cheapest possible way and ‘fuck it we’ll just see what happens.’ So, the scam back then to get over the border without working papers was to have whoever was doing the show in Canada write a fake letter from their fake record label saying that they were inviting this band over to record. And everything they have, all the merchandise, is all promotional and not to be sold and blah, blah, blah and it usually worked. Actually, it almost always worked, until that day. In retrospect, I can rewind and look back on everything that happened when we got up to the border and I can tell you, “oh, that’s why they pulled us over. Because we’re stupid.” So, the first thing they ask you is if you have anything to declare. So, I’m driving and what’s the first thing I say? “Uh, what are you supposed to declare?” “Firearms, drugs, alcohol, anything like that.” “No, no, we don’t have anything like that.” “OK. Well, pull over right over there.” So, they pulled us over and made us get out of the van, questioned us, opened up the van and we’re sitting in the little office where they’re questioning us and we start seeing these uniformed guys carting away our gear. It’s like, ‘what the fuck is happening? Where are they going? Is there another show here?’ [laughter] Finally, someone comes back in to talk to us and told us we were illegally transporting goods across the border and that we were being charged or fined for that, saying that we lied to them and that they were seizing everything we owned. We were like, “what are you talking about? You told us what we’re supposed to declare and we don’t have any of that.” “Yeah, but you have all these records and t-shirts.” We were like, “but look at our recording contract, it says all that stuff is promotional.” And the dude was just looking at us basically saying, ‘I know what you’re up to you fucking idiots.’ They were basically saying you could lose all your shit and stay here and we’ll put you in a cell, or you can pay a few thousand dollars and you can have all your shit back and go. That came after us being there for eight or nine hours. I mean, it was 1998 and we were in Jesuit and playing shows where we literally got paid $20. We couldn’t pay for that shit. Finally, Brian Benoit, who was our guitarist and the only one who was remotely close to being responsible in life, had a credit card. He was just, ‘fuck it. Just put it on my credit card.” So, we got out of there and there actually was enough time for us to make the first show and play after Botch. So, we start bolting down the highway and…

Wait a minute. They still let you into Canada? Even after you were transporting supposedly illegal goods?

Newton: They let us into Canada. We paid the money and they let us in. That’s all it took. If I had known that, I would have immediately been, “Brian, give them your fucking credit card!” At first, when we were there and they weren’t going to let us in, we were like, “OK, fine. We’ll leave. We’ll just take our shit and leave.” They were like, “no, you can’t. You lied.” And they just held us there and no one would talk to us for hours and they finally said, “if you pay this fee, you can go.” We’re like, “you mean go into Canada?” It’s like, ‘what the fuck?’ We got fully shook down. Now, the details of what happened next are hazy. It was night time and we started bolting to get to this show. We get about an hour away and then it was a dead stop on the highway, just traffic at a total stand still. There was no movement. We’re just sitting there and we look down the highway and we start seeing truck drivers shutting off their trucks, getting out and talking to each other. We’re like, “OK, that’s a bad sign.” Turns out that on the highway ahead, a truck carrying plate glass overturned and there was just shattered glass everywhere. So, they had to clean up the crash then a Hazmat squad came to clean up all the glass. We were there for hours and didn’t make the show. When traffic finally picked up, we had nowhere to go and we were tired as fuck. We decided to pull over in a rest area, sleep there and make it to the next show which might have been Ottawa. So, we pull over and I’m sleeping on a bench, one dude is sleeping on top of the van, other dudes are sleeping on the sidewalk, we just looked like a bunch of shitty bums. We woke up when the sun came up and we’re like, ‘all right, we’re back on track.’ We start driving and a couple hours into it all of a sudden our van starts fish-tailing like crazy. It’s just swerving and almost skidding across the entire highway. We had blown out both back tires and the rear suspension. So, we had to wait hours for a tow, the tow finally comes and he’s like, “there’s too many of you.” So, we had to wait for a flatbed and we just hid in the van while they drove and dropped us off at a Ford dealership, which was closed by this time. It was night and we missed another show. So, we just decided to sleep there in the Ford dealership parking lot. Wake up the next morning thinking they’ll fix it and we’ll make it to the next show. Well, that dealership was like, “we can’t fix that.” They didn’t have any of the parts we needed or anything. So, we had to call AAA again and tow us to another Ford dealership that was fucking far away somewhere. None of us had the AAA-plus plan, so we’d get them to tow us as far as they could and drop us off, then we’d call them again to tow us some more. Finally, we get to this dealership and they’re like, “we can fix it, but we can’t get the parts until tomorrow.” So we had to wait there again, they got the parts, fixed it the next morning. We get in the van and drive and we get to Montreal just in time to load right on to the stage and play the last show of the Canadian dates. We played one set then drove back to the states.

What sort of impact did Jesuit not being there for those few days have on the tour?

Cook: Well, it was definitely a drag. It was a bummer to leave anyone behind especially because we caravanned on this tour. That was a weird phenomenon that doesn’t really seem to happen anymore, but on that tour and tours prior, you always stayed at the same spot as the other bands, you always caravanned so you rolled into the same gas stations and hung out at the same places. So, them not being around or being at the shows it was literally, “it’s a drag not having them to hang out with all day.” But it was also weird because looking back on that now, it was still the pre-9/11 era, so you didn’t need a passport and we didn’t even have to show IDs. We pulled up and we had this fake recording contract saying we were recording in Toronto or whatever and they pretty much just waved us through. They asked us if we were all citizens, we said yeah, they asked us if we were sure and we said, “we can show you IDs” and the border patrol guy is like, “nah, I don’t care,” which was literally the response back in 1998. It was pretty fluid for us. I don’t know why Jesuit got fucked with. They actually called from the border to the promoter and we talked to the border patrol guy through them saying, “you let us through. Why didn’t you let them through?” The border patrol officer was like, “well, you shouldn’t have gotten through.” It was like, ‘OK, this call’s over. Never mind.’

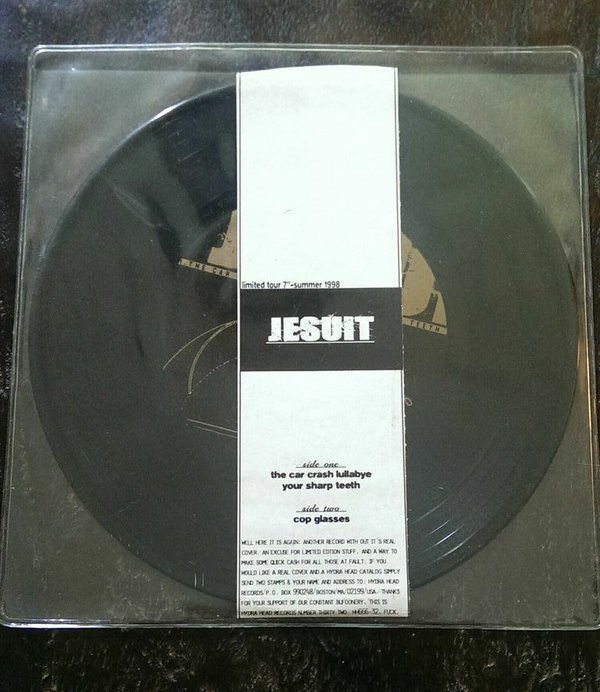

Jesuit’s for-this-tour-only 7″. A favourite of Canadian Customs.

Jesuit’s for-this-tour-only 7″. A favourite of Canadian Customs.

What were the turnouts like?

Newton: It really depended on the town. I remember Montreal had a pretty good turnout. I couldn’t give you numbers, maybe 100-150? Montreal had a really good scene back then and I think Ire and Cave In played that show. Our tour crossed paths with their tour, more than once on that tour, actually.

Weinman: We really had to earn our stripes on that tour, but you have to remember that Botch and Jesuit were still pretty new bands as well. Jesuit had formed out of other bands from the Virginia Beach area like Cable and Channel, and there was the Hydra Head connection, so there was a little scene around that stuff and we were lucky enough to have people come to those shows who would be there to check out the tour and every band and hang out with their friends and be a part of the subculture. We were lucky enough that it wasn’t like the metal or rock scene where we were playing clubs where everyone’s drinking beers and not giving a shit about the first bands. For us, even though we were playing earlier, people were there for the whole experience. And it was like, “there are 30 people here. This is awesome,” and when you’re playing a small basement 30-50 people is packed and when you’re playing a small venue or a VFW hall, 100 people is insane. I’m not sure how many people were there and how many people liked us, but for us whatever it was it was certainly a lot of people.

Any other incidents of note you’d care to share?

Newton: We were crossing the border back into the states and we were crossing the border together because I think we had a show in Syracuse or something like that and right as we got through the border, Dillinger speeds up right in front of us and unloads four dozen eggs right on our windshield. We were laughing, but I was so broken and dejected by that point. I literally wanted to pull the van over, cry, walk out into the woods and stay there forever. But, we cleaned the van off, drove to Syracuse and played a show with The Swarm and I think that was Dillinger’s last show with us. From there we did east coast shows and they were as you would expect, they were good shows. I think we went all the way down into Florida. In Atlanta, we played Under the Couch and in the middle of our set, Brett needed to take a piss. So, he just put his bass down after we played a song and just ran off the stage and we’re all just standing there thinking, ‘what the fuck is going on?’ On his way back to the stage, he tried to jump over a chair or something and he tripped, fell, sprained his ankle and couldn’t get up. Meanwhile, we’re all just standing on stage wondering where he went. Finally – and we were real professionals – we got on the mic and we’re like, ‘Brett, where are you, man?’ And he’s yelling from the back, ‘I’m on the floor!’ We went down to Florida and I remember playing with Cable and Isis and Isis only had their demo out at that point and Randy Larson from Cable was playing in Isis as well. From there, we went back up and headed west, had a weird moment with a dude on a highway in Mississippi or something. We were following each other to every show and usually crashing at the same houses or whatever. We’re on the way to the show, we were in front and the guys in Botch were flashing their high beams at us which was the code for pull over for gas or whatever. So, we’re driving along to the next exit and while we’re driving, this dude drives up right next to us, and he’s driving crazily. He’s waving at me like he’s insane and we’re all wondering, ‘what’s wrong with this dude? Is he OK?’ He’s looking at me and starts making the universal sign for a blowjob. And I’m like, “guys, look at this dude! What’s up with this guy?” and he’s just pointing at me and waving and doing that blowjob motion. We got to the exit to pull over because that’s what the Botch guys signalled and I’m thinking, ‘oh, this should be interesting.’ We get to the stop sign at the end of the exit and the dude speeds right up to next to us, rolls down his passenger window and he says, “hey, I was wondering if any of you guys want a blowjob?” I just turned to everyone and said, “any of you guys want a blowjob? No? Well, none of us do, but the guys in that van definitely do.” And we just took off, pulled into a gas station and the dude pulls up to the Botch guys and immediately he’s like, “how about you? You?” and they’re all like, “what the fuck are you talking about?” I don’t know what happened after that, but I think [Botch drummer] Tim [Latona] went into the bathroom, not knowing what was going on, and the guy tried to follow him or something. It’s weird, and funny. Lots of weird shit happened on that tour. There was the night we played in a trailer park with a band called Cop Sodomy. And they were good! Seriously. There was this group of crusty, train hopping kind of punks that was showing up to a bunch of the shows which I thought was kind of strange considering that we weren’t crust punks, but that was kinda cool.

Cook: I remember a lot of things breaking. Everyone had van trouble. We almost didn’t make it to the Philly show because our van broke down. Jesuit’s van broke down in Canada. Our side door wouldn’t lock, so our van was basically unlocked the entire tour. We didn’t have a trailer either. My bass broke, Dave’s amp broke, people broke, there were trips to the hospital. I think maybe the most memorable thing…have you seen that movie Green Room? We played in Little Rock, AR. We played what was basically a farm with a chicken coop and all this stuff. We had the address to this place, we rolled up and some crusty kid with long dreadlocks greeted us at the entryway to the property. He was a nice kid, a fan and all, but we were basically playing in a chicken coop with a stage built into it. The owner was a crackhead; he had gone to rehab, but he got into financial trouble, trouble with the law, his mom had taken over the property and now she was the legal owner and he was trying to the rights to the chicken coop back and part of his way of getting back on track was to have shows at this spot. That was his method of reforming himself. And the opening band was Cop Sodomy and they were kind of like between Chaos A.D.-era Sepultura and Roots-era Sepultura with kind of that groove mosh. They were a little crusty, but kinda nu-metal at the same time. They kind of gave us a heads up, saying “this town is kind of weird right now. We’ve learned how to extract dextromethorphan from Robitussin. No one has to drink a whole bottle of Robitussin before you go to a show anymore, you can do a shot of this extract.” And all of these kids were total zombie, cough syrup, crust punks. The vibe was real weird, very backwoods, lots of doped up kids and we finally met the owner and he was really worried about the sound curfew and neighbours complaining, but at the same time he wasn’t worried because they had noise complaints in the past and he’d just hand off dime bags to the cops and that took care of it. Then, he said it was really important that this show space doesn’t get shut down because it was the only way he got to meet underage girls. The whole scenario, everything about the entire scene was just creepy and wrong. There were no skinheads, like the movie, but it was more like, ‘man, different parts of America operate really differently.’ Little Rock is definitely a far cry from Seattle. The show actually wound up being pretty good. Cop Sodomy was pretty awesome, the kids were stoked, the main issue was that we didn’t have a place to stay and every kid who offered up their place was very hospitable, but the trade off was that we had to buy Robitussin for them [laughter]. That weirded us out so we ended up going to some diner with the plan of getting a hotel after we ate. This was still the era of phone dialers. We rolled with a dialer and we were at this cafe and we were taking turns at the pay phone outside using the dialer to make free calls home. Eventually, Tim was trying to use it and the operator came on and said she was sending out the cops. He hung up and ran back in the diner and two minutes later a cop car pulls up and they come in, walking around eyeing everyone suspiciously. Nothing actually came of it, but it was one of those weird things where they were really concerned about someone making free 25-cent phone calls, but not the drug dealing, chicken coop, underage girl guy with Cop Sodomy playing.

What’s the story with the shit in the cup?

Newton: Ben Weinman hid a piece of his own shit in Botch’s van. He did it in front of my parents’ house. They didn’t find it for like a week.

Cook: Yeah, yeah. So, like I said, our side door didn’t lock and we probably brought it upon ourselves because we definitely initiated a lot of the prankery between bands. My general understanding of tour prankery, though, is that you don’t fuck with the inside of someone’s van. You want to write something in lipstick on someone’s windshield or smear peanut butter on the door handles, that’s funny. The inside of the van is like someone’s “safe space.” You’re kind of fucking with someone’s living room. Again, I was super-poor on this tour so I was buying a jar of peanut butter and a bag of bagels and living off that every day. There was a bag of food we had on the first bench seat that was filled with non-perishable stuff. We parted ways with Dillinger a couple days prior and there was a weird smell in the van. But it wasn’t like a shit smell, which was the weird thing; it was like something really stale, like an old banana or something. We were looking around for half-eaten food and we couldn’t figure it out. We finally did a thorough van clean and went through everything. There wasn’t a lot of trash, we went through the food bag and there were two red kegger cups that were taped together with a note that said, “thanks for putting up with our shit, Love Dillinger.” But the thing was is that it didn’t smell, we weren’t even sure if that was it. Nate was there and he was like, “dude, don’t open it. Don’t do it.” But curiosity got us and sure enough there was a perfect little turd in the cup duct taped shut and that was the culprit. We threw it out, we threw out all the food in the bag. I was hungry and didn’t have any money and I guess they had the last laugh.

Weinman: At the end of our run, I took a big shit in a cup and put a note in it that said “thanks for putting up with all our shit.” They had this food bag and I put it in that bag. I never found out what happened until later. I talked to Nate who informed me that apparently a week went by and they couldn’t figure out what was going on. They were cleaning the van out, doing their laundry, dry heaving and it was driving them nuts. One day Brian found the cup and in it was this giant shit. That’s what I heard. I decided I wasn’t going to chime into the war. I was just going to totally bomb them and then leave so they couldn’t retaliate. Call it a pussy move if you want, maybe, but fairly soon after that, we went to Europe with Botch and we shared a bus. I was like, “man, I’m fucked.” It was a month-and-a-half in close quarters with these dudes who I essentially shit on. I was never going to know on a daily basis what they were going to do to me.

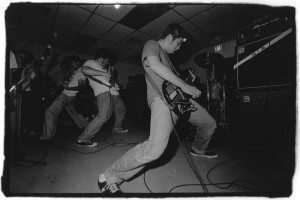

Jesuit

Jesuit

Where or how did the tour end? It’s well-known that soon after, Brian ended up in Dillinger and Nate ended up in Converge?

Newton: At the time, I had just filled in on bass for Converge. After that tour, Jesuit was in a weird spot. I think we wanted to continue, but Jesuit was a definitely a strange mix of people and personalities. We were pretty dysfunctional and I don’t think it could have lasted. As a side note, that part of my life was probably the lowest I’ve ever been as far as my mental and emotional state is concerned. So, I put every ounce of energy I had into the band but it wasn’t creative energy, it was me running away from my life. I was taking every ounce of energy to put the band on the road and just being a crazy aggressive asshole on stage all the time. In retrospect, there were a lot of things that I’m definitely ashamed of and would not do now. We made our way back across the southwest, but I’m having a hard time recalling. We definitely played New Mexico because Santos [Montano, Old Man Gloom] was there and some of the other friends from the area I met through Aaron and Santos. I remember playing in Riverside, CA at like this half indoor-outdoor, barn-like venue. We played Gilman… our famous Gilman show that got Jesuit banned. Us and Botch played there with Ire and Cave In and somebody else. Jesuit didn’t take anything seriously and we, or at least I, expected that any stupid joke I made was understood to be tongue-in-cheek. And that was a stupid thing to assume. Basically, I was like, “we’re Jesuit. We’re not racist, sexist or homophobic, but girls with moustaches gotta go.” People got very angry about that. A few women who were there were very visibly and vocally angry about it and in retrospect, I don’t blame them because I was being an aggressive prick trying to get people angry. I got exactly what I wanted, or at least what I thought I wanted. It made me learn a lot about myself. The end of the night rolled around and they would have the round table discussions for payment and they were like, “we don’t want to pay you. You’re an asshole.” And I was. In the very tiny circle that followed hardcore at that time, it all got blown out of proportion. What it made me come to realise about myself – and here’s where I become the totally politically correct hip guy – it made me realise how I was using my own privilege as a male to make jokes about things that touched raw nerves. I want to make it clear that the thing that happened at Gilman was an important moment for me. At first I thought of the response as some sort of overly politically correct groupthink. I couldn’t see the irony in a man standing on stage in a male-dominated music scene making jokes about women who couldn’t understand why women were angry with him, even though the jokes seemed harmless and childish to me. Didn’t they know I wasn’t serious? Didn’t they know I didn’t really mean it? It took years for me to realize that it didn’t matter that I wasn’t serious. What mattered was that I was comfortable enough to make a childish joke at other people’s expense and then expect them to be OK with it. Basically, I was a person with power and influence, through music, who was taking shots at people without power. Getting called out for it at Gilman was a turning point in my life. It forced me to look in the mirror and acknowledge my privilege as a man and how I used it to essentially bully people. Honestly I’m thankful that it happened and I feel like I’m a better person for it now. I can look at it and laugh and see why I or someone else thinks it’s funny, but I can also look at it understand why it of course pissed some people off. Would I do something like that now? Definitely not. Things got interesting after that though. Word got out about that so people started contacting other promoters and there were other shows we showed up at and people didn’t want to pay us or didn’t want us to play or whatever. It got kind of silly and felt like a bit of a witch hunt at the time. Though some good came out of it in that it forced me to take a little bit of a look at myself and think about how words affect people. We got all the way up the west coast. We played Seattle and that was where Botch left the tour and it was a fucking great show. From there we had to make our way back across the states. I remember we had two days to drive from Seattle to Denver and another band from Seattle joined up with us at that point called Jough Dawn Baker and they were fucking great. They barely made it to the show in Denver at Double Entendre Records because they had a van that kept dying all the way out there. They made it, played that one show and were like, “yeah, we’re going back.” I honestly can’t remember anything that happened after that.

Cook: This band called Jough Dawn Baker, who had a couple records out and were fucking awesome, were supposed to do the rest of the dates after Seattle back out to the east coast. We broke down outside of Denton, TX after a show with Jesuit, Rubber Soul Man and Assück. That was an awesome show, definitely one of the best shows of the tour. We were going to drive to stay with Tim’s parents in New Mexico. We were driving at like two or three in the morning, we put the van in cruise control and the van shot up to 90 m.p.h. It’s like we had floored the accelerator, but we couldn’t slow it down; the accelerator wouldn’t un-stick and we were blazing down the interstate at 90. We were able to get it into neutral because we were trying to brake and it wouldn’t slow down. We got it over to the side of the road, all the tires were smoking, we got towed to a Pep Boys and the engine was totally fried. We rented a budget cargo van, missed the Phoenix show and another show on top of that and drove straight to Huntington Beach and stayed with a friend there. We did the rest of the tour home in a cargo van with no seats. When we got back to Seattle it was supposed to be us, Jough Dawn Baker and Jesuit all the way back to the east coast, but we couldn’t figure out a van situation that was affordable, so Jough Dawn Baker took over. They played Seattle, then Denver, then their van broke down. They rented a box truck and loaded up a box truck with everything, including two of the five guys in the band and rode back to Seattle that way, in the middle of summer after they did a two-date tour [laughter]. So there were a lot of broken down vans and missed shows, but I guess that’s the way you roll when you buy a van for $1000 [laughter].

Weinman: They definitely had some volatile situations going on. Jesuit was definitely a fiery group of people, but Brian was always chill and calm. Nate was always talking shit on people, telling jokes, calling people out in the crowd. If someone walked out while they were playing, he’d stop, point them out and make fun of them. He was good at making everyone uncomfortable in a room and he probably did that to the guys in the band. Brian was always super-chill and relaxed and no-drama guy. We liked him right away, got a good vibe from him right away and became good friends on that tour. We didn’t have any idea that we were going to lose John, our guitar player at the time, and the Converge thing wasn’t in the picture, I don’t think, but there were signs that the band wouldn’t last much longer just based on arguments or whatever. Either way we had a great time with all of them and, like I said, it was the first time we felt any real camaraderie with other bands.

What were things like for you when you got home? And how did you feel this tour shaped you going forward?

Weinman: I remember us being bummed when we left that tour, but then trucking it up to the Milwaukee Metalfest and that was just a fucking spectacle. That was definitely an interesting point in the lifetime of Dillinger which was attached to that tour because technically it was the last show of that tour for us. That whole fest was ridiculous. Nate’s moustache comment also fucked with us after because after Brian joined the band we played Gilman and we had to hide the fact that Brian was in Jesuit and we had Jeff Wood [Shat, ex-M.O.D.] on bass and we were horrified what was going to happen. But nothing happened.

Newton: Jesuit didn’t last very long after that. Less than a year. It was kind of already in the works before Brian or I had other prospects. It was not meant to work. In retrospect, I can look at myself and realise that I was probably impossible to work with. I had every quality that I look to avoid in a band member, so yeah, it was bound to happen. When we started the band, we wanted to write all this crazy heavy music, but every time we had anything new, it was like, ‘ok, let’s tour!’ We just never started writing again. We toured ourselves into the ground to the point where when we came home we didn’t want to see each other, much less a guitar. Brian was smart. We knew on that tour that John was leaving Dillinger and they needed a second guitarist; it was a good opportunity and he took it. And in my case, with Converge it was that Jesuit broke up and they still needed a bassist. I think that tour broke us and it wasn’t because we weren’t a good band or couldn’t write music; it was that the four people in the band were incompatible on a personal level. I love all those guys and we’re all still friends, but not two-months-in-a-van friends and we wanted different things from each person and in some cases it was things the other person wasn’t capable of.

Cook: I think this tour made me a lot more apprehensive about touring, in all honesty. The touring we had done prior to that, we were young and felt indestructible. That was the tour where everything that could go wrong went wrong. I think it was also the beginning of us as a band not totally getting along. I remember being frustrated a lot of the time with some of the other guys and I’m sure they were frustrated with me. That was the kind of tour that most bands go through and it’s the kind of tour that breaks bands up. We persevered through it, gave it another go, came back and did We Are Romans and things turned around from there. It was kind of the last stumbling block before things picked up a bit. It was also a tour where Jesuit fucking ruled. I still hang out and text with Nate all the time. Dillinger obviously went on to do what they did, we did more tours with them and they were probably our closest allies, band-wise for the remainder of the Botch years. There were a lot of great memories from that tour, but it was also the tour that revealed how vulnerable you were and for the next ten years of touring for me, whether it was Botch or These Arms Are Snakes, it made for a lot of apprehension for me going out on tour. So much shit when wrong that it was always in the back of my mind that shit ana go wrong really easily and then you’re just stranded in Texas in 108-degree weather with no money and no way home. That tour kind of ended our prankery as well. We used to be driving along and we’d shoot fireworks at each other and stuff like that. It was fun, but karma finally caught up to us and we paid the price. Now, it’s not the matter of being the wild crazy band on tour, it’s more like make the shows count. That was my big takeaway from that tour.

The gang’s all here: end-of-tour group shot.

The gang’s all here: end-of-tour group shot.