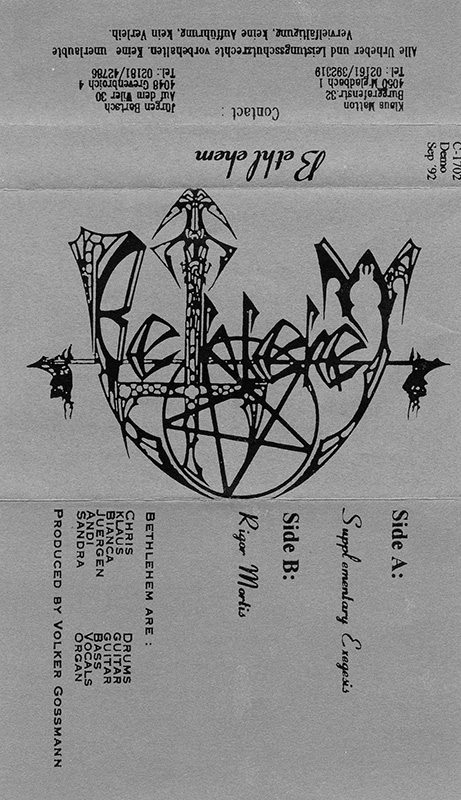

Next month, Decibel Books will release Black Metal: The Cult Never Dies Vol. 1, by Dayal Patterson, the author of the authoritative black metal history Black Metal: Evolution of the Cult. But, like you, we can’t wait that long to dive into the secret histories of bands as diverse as Satyricon, Kampar and Manes. So, today we’re unveiling an exclusive excerpt from The Cult Never Dies Vol. 1 in the form of early days of dark metal—and depressive suicidal black metal pioneers—Bethlehem.

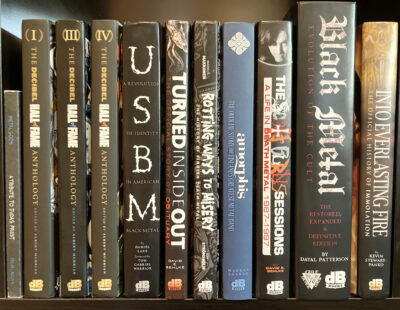

Dive in and pre-order a hardcover, hand-numbered, limited to 1,000 copy of the book right here.

Though they consciously sidestepped the black metal tag at an early stage in their career by branding themselves with their own label, “dark metal,” on the album of the same name, there is a pretty good argument for declaring German veterans Bethlehem the forefathers of modern DSBM. At the very least, the group were a major catalyst in the development of the genre as a more self-contained form of music, one that discarded many of black metal’s more familiar traits while picking up a few new ones along the way.

Haunting, tortured and melancholic, Bethlehem’s early works drew heavily upon the more despairing end of the black metal spectrum while simultaneously offering something that immediately stood out as somewhat unusual—even idiosyncratic—within that context. Where other bands of the time were immersed in “external” grandeurs such as the natural world or Satan, Bethlehem offered a more internal and personal perspective, with biographical explorations of the human condition given just as much emphasis as more abstract philosophical or spiritual concerns. Likewise, their music made little attempt to fit into the then-dominant Scandinavian template, despite it clearly being informed by the music coming out of Norway in the early ’90s.

Formed in 1991, the band had only one consistent element in its lineup throughout a two-decade-plus existence: bassist, lyricist, songwriter and keyboard player Jürgen Bartsch, a man who, coincidentally or not, shares his name with one of Germany’s most notorious serial killers. There can be little doubt that Bethlehem’s dark and eccentric works have acted as something of a mirror to the often strange and extreme conditions of the multi-instrumentalist’s personal life, and certainly the man himself maintains that this is the true source of inspiration for the group. We speak for several hours, and I find him surprisingly easy to talk to; quintessentially German in many regards, he is friendly and polite, yet also straight-talking, his warm tones and matter-of-fact descriptions somewhat underplaying the rather disturbing nature of his experiences, not least his childhood in Grevenbroich, a town in the west of Germany.

“Basically this already started in my youth, though I did not know that then,” he explains of Bethlehem’s genesis. “I was born in a part of my hometown which was called ‘slag heap’; this was a place people went to, especially after World War II, because you could find work at the mine there. My father arrived there together with my mother and they built themselves a hut or cabin made of wood and sheet metal. This was a kind of slum, you know, nothing special. Later it got bigger because more and more people went there, and it became this typical sort of brick-stone suburbia that nobody wants to live at because all the human scum is living there, basically.

“The street I was born in was… yeah, a pretty antisocial kind of place, I would say,” he continues. “My father was a drummer in a local rockabilly band and was always drunk, and you always had these people hanging around at home, his mates and other people. Nearly daily I was beaten up in my childhood and teenage times or otherwise humiliated—also in a sexual way, I must say. Definitely not a nice place to live at. The tradition—well, not the tradition; the only opportunity, really—was to work in the mine, or become a criminal maybe. There was nothing between that. Most of my classmates never finished school—though it was forbidden by law, most of them began working in the mine at 15 or 16. Actually, just a few months ago, my best friend [during those years] got in contact with me; he is back from jail. I think him and his brother murdered someone in the past, and this was a bit like a flashback to that place.

“I did not tell people in the past, even band members, that I came from there. It’s embarrassing coming from those places—this is something no one wants. Germany is a rich country; they all want to be wealthy and have nice houses and jobs and such. If you are coming from such places, you are an ‘antisocial’—who wants that? There’s no future, no opportunity; if you stay there, you are doomed, you are lost. You are basically dead, because it will stay the same forever. Lately I read in the newspaper that they want to destroy the whole quarter and build a mall or an industrial-orientated area. Which would be good—to destroy this place forever.

“Anyway, the fortune—and I really must say that—the fortune was that a friend of mine, he was a criminal, and he broke into houses to fund his drug addiction because he already was addicted to cocaine at 15. And when I got to 16, as a birthday gift, I got a bass guitar—he gave it to me because he could not sell it, I reckon. It was a Fender Jazz bass, and this resulted in me starting to play Motörhead a lot—I think Lemmy was my one and only instrument teacher at that time. Also Tom Angelripper of Sodom, actually—those were bands I worshipped at that time, my heroes, and this was the beginning of my musical career, I suppose.”

Rather tragically, the aforementioned instrument—ultimately the catalyst for all that was to follow in this unique character’s life—would end up being sacrificed in a bizarre and rather sadistic rite of passage that Bartsch was forced to take part in two years later.

“Both this bass and my first amplifier—which was an Orange amplifier, because I wanted to sound like Motörhead—got burned in a fire when I was 18 years old, because the tradition in my street was that if you reached 18 and were still living at your parents’ house, you were thrown out and everything you owned was burned in a big fire behind the houses, with all the stupid people from there sitting round drinking beer, having fun. So, I was forced to burn my own bass guitar, as well as all my records and all my other shit, and the next day I was standing there with only a plastic bag and a sandwich I got from my mum.

“I went to Berlin because I was homeless and I wanted to escape this fucking place,” he continues. “I managed to join a so-called ‘sleaze band’ called Weird Kong. At the end of the ’80s, bands like Guns N’ Roses and L.A. Guns became pretty big, and I found a band that was playing like this, which was good because we had a major deal with Ruff & Roll Recordings, a label which specialized in this kind of music, and they released our album [in 1990]. The album sounded a bit like the Rolling Stones, the Quireboys, L.A. Guns—this sort of music. We even did a tour with Skid Row, but I was fired afterwards because I pretty quickly became addicted to cocaine and alcohol and ended up in too many fights. I think this is because I was coming from a violent background—it sounds funny but I missed it. I needed violence. So, I was no longer tolerable for my bandmates.”

Bartsch’s time in Berlin was apparently a troubled one, colored by heavy drug use and the deaths of a number of friends he met there, a reflection of his lifestyle and choice of company during the period. Losing his position (and, importantly, a monthly wage) as bass player for Weird Kong certainly gave Bartsch a good excuse to escape both the city and the increasingly destructive scene that existed there, and he soon began drifting through Germany until he eventually ended up not too far from the town he’d escaped just a year or so earlier. However, having now played in an active band, he at least had some idea of what he wanted to do with his life, so he decided to find another group, only this time one with a heavier sound. His opportunity would soon come thanks to a chance meeting with a member of a local thrash/death outfit called Morbid Vision.

“I ended up stranded in a city close to my hometown,” he recalls. “Fortunately, I found a job there, although I don’t know if I should mention it because it’s a bit weird. I worked in a sex cinema—this was my first job in this city and was gross because I basically had to clean these small rooms for perverts. They watched these wee and poo videos there and wanked all over, so I had to wipe sperm away. But at least I had an income, so I could rent a pretty small flat on the sixth floor of one of these dirty houses that you walk into and it directly smells of urine. However, I was glad I had my own bed, you know? I always had to share a bed with my sister back at home, and these are things which are still very important to me and why I can’t stand being on tour sometimes, when you have to sleep in the same bed as your bandmates. Anyway, in the city I met the [eventual] drummer of Bethlehem, Marcus [Losen], because he played in a psychobilly band at the time—it was him and two guys from England; they toured the U.S. with Billy Idol, so they got pretty big. Anyway, at some point hanging with them at their rehearsal room, I had to go wee, and in the toilet I met Manfred [Markowka, better known as ‘Balu,’ bassist and vocalist of Morbid Vision]. They rehearsed in the next room of this rehearsal area and during this wee and this small talk, I discovered they needed a bass player, so I got in this thrash band then.”

Bartsch’s time in this short-lived band would be relatively brief, not even long enough to appear on the group’s sole release, a five-song demo released in 1991. It was long enough, however, for him to make a personal and musical connection with one of their members, second guitarist Klaus Matton.

“Although I wanted to play in a metal band rather than a sleaze band, thrash wasn’t really what I wanted to do,” Bartsch explains. “This band was not so satisfying somehow, especially this solo guitarist. He wanted to be the leader of the band, and the songs I wrote, this was nothing he could feel; he was more into thrash metal and the old metal styles, and could not identify with black metal. It was kind of new at that time, of course; you had Venom, Bathory, Hellhammer, Celtic Frost and all that, but the return of it—bands like Beherit, Mayhem, Rotting Christ, Impaled Nazarene, Darkthrone—this was new and refreshing. We liked this a lot. So, after a year, me and Klaus left to do something else.”

Matton had also decided that Morbid Vision was no longer a suitable musical vehicle, and now sought to create a new band which would allow him to push his playing into darker territories. Together with Bartsch, he shared not only a passion for the new wave of black metal that was quickly emerging in Europe, but also the still-raw memories of his own traumatic youth.

“The strange thing is that Klaus had similar experiences to me,” explains Bartsch. “When he was 10, his father hung himself. His father had a small painting company, but was addicted to poker and blackjack and lost it all—and much more—and I think the only way out was committing suicide. This is when Klaus was 10. Then he had some hard years together with his mum, but she died from cancer later when he was 12 or 13 years old, so he also did not have the best years and was in a kid’s home, I think, until he was 18.”

It was this unusual dynamic that seems to have united the band’s early lineup, the group being completed by drummer Chris Steinhoff and vocalist Andreas Classen, two characters that Bartsch quickly recognized as kindred spirits because they too came from fairly troubled family backgrounds.

“Classen was the all-time black metal fan,” says Bartsch. “Even before bands like Mayhem, he was into Bathory and old ’80s stuff. He worshipped Venom and had the biggest collection of them all. He had every bootleg he could find; he was addicted to it. It’s a sad story, but he actually lost his front teeth the first night we met him; it was at a local metal club and they played Sepultura’s Beneath the Remains or something and he headbanged, and Klaus’ head hit Classen’s mouth and he lost his teeth. The drummer came from a completely different city and was part of this crossover punk/metal/hardcore scene. He was a silent kind of guy, but he was known to hate skinheads. Many times he got in fights with them and was known as the ‘bully’ in his circles. This guy fit with us—especially in the beginning of Bethlehem, we were all antisocial and coming from broken homes, and that was important, to play with people like us. I would not say it was fate—this would be going too far; I do not believe in this—but it was a special thing, which maybe resulted in the fascination with darkness.”

It was this fascination that led to the creation of the “dark metal” concept, a theme the band adopted almost immediately. At this time, “black metal” literally meant “Satanic metal” to most, and Bethlehem were clear that they did not consider themselves a Satanic band—though a number of their early lyrics suggest otherwise. Moreover, though dark, the members did not view their music as “evil” (a popular buzzword of the time), and instead paradoxically saw it as a source of light and hope from a life where drug addiction, abuse and suicide was claiming many of their friends and contacts.

“Our music reflected all these negative things from our youth,” Bartsch considers. “I would not say it was therapy or something, but at least it was relief. You could channel all of the negative aspects of our life. I never went back to where I grew up—this part of the city is now taken over by Russians and gypsies, and sometimes you can read in the newspaper if the next guy got killed or so—but though I spent years in different cities, I never could get rid of the smell… this suburban place was with me wherever I went. I could not escape it. But with Bethlehem I could, and I became a completely different person than people expected I would become. I did not become the ‘antisocial’ as my father did and my neighbors did; I became something else and this is based on Bethlehem. Bethlehem was a relief—it was something beautiful that I never experienced before in my life, like a butterfly, which was all based on a random meeting in a dirty, stinking toilet.”