This special feature originally ran in the June 2016 issue of Decibel.

Over a quarter century has passed since Mayhem’s “Freezing Moon” stunned its Leipzig audience. Dubbed black metal’s second wave, Norway’s explosion of extreme music wasn’t an intentional, synchronized movement. It was a snapshot of wanton rebellion, encouraging experimentation and fueled by youth. But for several black metal luminaries, expectations based on their teenage creations continue to shadow them, even decades after evolving past the genre.

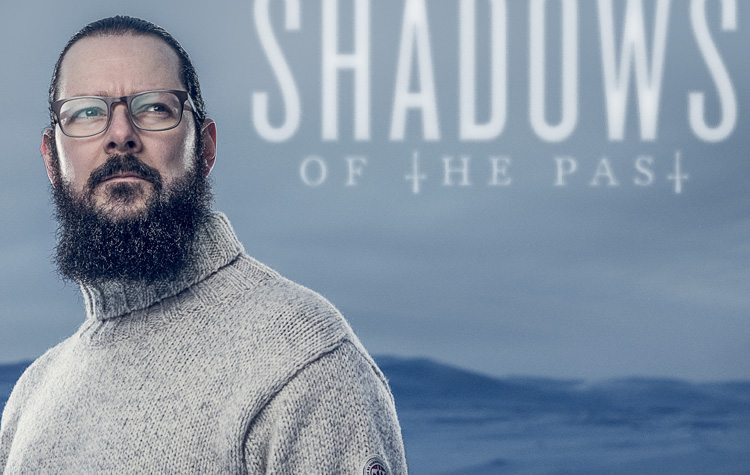

AS THE SHADOWS RISE

“I think I’ll forever be my own little brother,” admits Vegard Tveitan—better known to the metal community as Ihsahn, prolific solo artist and vocalist/guitarist of Emperor. “But now that we’ve done these occasional Emperor shows and I’m releasing my sixth solo album, I’ve been doing solo stuff for as long as I did Emperor. So, now I’m much more comfortable with my career as a whole. [The past] is more like a blur now, if anything.”

Arktis—mentioned above as Ihsahn’s sixth solo effort—reinforces his stylistic departure from Emperor’s legacy. Honoring the metal of his formative years with rousing hooks and classic metal choruses, he still detours at will into shadowy jazz [“Crooked Red Line”], dance beats [“Frail”], and prog rock [“Disassembled”]. Those seeking the raw fury of Emperor’s seminal works may count the seconds before Arktis’ first blastbeat launches 33 minutes into the album. But Ihsahn—17 years old while recording In the Nightside Eclipse—doesn’t resent his earliest albums, and understands why Emperor’s initial offerings resonate to this day.

“I’m proud of them for what they are,” Ihsahn shares. “We were so young when we recorded them, and of course didn’t have experience and weren’t especially good musicians or anything. But we had that teenage drive and conviction and willpower. We had a very clear idea of what we wanted to create, and I think that youthful courage shines through. Those albums continue to sell—even to people who probably weren’t born back then.”

Ihsahn’s quick to mention that Emperor originally struggled to garner positive coverage from metal media. Any notion that they were immediate critical darlings is as much a myth as Freyja’s cat-drawn chariot. “I think Emperor as an entity is far bigger now than it actually was when we were ever active,” Ihsahn suggests. “It’s just grown with myth and nostalgia and all that.”

WOLVES EVOLVE

“I’m sort of hung up on time; warped time and space,” shares Kristoffer Rygg, vocalist and founder of oft-mutating experimental collective Ulver. “We’re always looking to the future or the past for answers or inspiration. But the sort of hang-up on ancient history is not so strong, I would say.”

Ulver circa 2016.

Ulver circa 2016.

Under the pseudonym Garm, Rygg was Ulver’s primordial scream tearing through the wilderness painted on their debut, Bergtatt. Now releasing Ulver’s 13th LP—an entrancing 80-minute venture into deconstructed rock and psychedelic ambience titled ATGCLVLSSCAP—Rygg’s nearly 20 years removed from the “ancient history” of their black metal trilogy.

“It’s strange, because they’re so canonized. And I appreciate that and I feel very proud about that. But, it’s probably the music I’ve made that for me personally is the hardest to connect to nowadays,” Rygg admits. “That said, it still blows me away putting Nattens Madrigal on, thinking, ‘Fuck, this is gnarly. Did I make this?’ It’s got that feral drive to it that’s sort of amazing to listen to, even now.”

After the trilogy, the experimental concept album Themes from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell formally buried their black metal pursuits. In case any doubts lingered, their next EP—aptly titled Metamorphosis—went full-on techno. But Ulver had already established they wouldn’t bow to expectations; the original trilogy’s middle album, Kveldssanger, is a forest-dwelling Norse-folk album with nary a scream or distorted guitar. Asked if there was ever trepidation to move past their black metal roots, Rygg’s answer is immediate.

“No,” he quickly laughs. “I don’t think we felt we had that much to lose. These were still early days. I might admit to actually being more conscious about those things now with Ulver, saying we can’t do this or can’t do that. But back then I didn’t give a flying fuck.

“Black metal was becoming a prison of sorts,” Rygg continues. “It sounds childish when I say it out loud, but it’s true. We still felt connected to black metal as an idea; more as an idea actually than a musical infatuation, by 1997. [Black metal] was getting quite big and getting noticed around the world and stuff, but by that time it had lost a lot of its initial draw for me. So, to us it felt like the most black metal thing you could do was say, ‘OK, let’s go make a fucking techno album.’”

HOW TRVE THEY WERE

“I really feel bad about stigmatizing whole generations, but those who came from all over the world to meet us in ’94 to ’96 at Elm Street Rock Pub seemed very intense and often quite one-track minded,” writes Gylve Nagell, AKA Fenriz, heavy metal tastemaker and one-half of Darkthrone.

While Darkthrone remains Fenriz’s most recognizable musical contribution, he’s explored doom with Valhall, released ambient music under the name Neptune Towers, and has encouraged eclectic listening habits for three decades. When an interviewer confronted him regarding his techno appreciation in the documentary Until the Light Takes Us, he famously retorted on behalf of Oslo metal musicians, “We’re not fucking living in a trailer camp just listening to Anthrax.” But that assumption followed the fans who descended upon his boozing post. “It was abnormal to me when the blackpackers first showed up at my Oslo pub Elm Street to try to tell me only black metal was real. What a joke,” Fenriz fires.

Darkthrone’s Fenriz (r).

Darkthrone’s Fenriz (r).

“But oh how trve they were,” he continues. “Many times we had code words to go to another bar to get rid of the worst fan boys. When I write it down it seems like we were douchebags, but really we didn’t ask for this attention. We were discussing life or death and bands like Coil or even Guns N’ Roses when a barrage of people from around the globe came asking about [albums and recordings] we had finished doing, and certainly had little to do with what we were going to record.”

Fenriz ponders what history would have been like without expectations intruding on the musical freedom he felt Mayhem co-founder Øystein Aarseth (AKA Euronymous) promoted. “When it all fell apart in late ’92 after Under a Funeral Moon was recorded locally, it was tempting to just use a Neptune Towers recording as Darkthrone’s new album,” Fenriz admits. “Would have fucked with people for sure.”

FROST AND FIRE

“We never saw ourselves as black metal,” confesses Ivar Bjørnson, guitarist/composer of Enslaved. “At the time, back in ’91 and ’92, black metal was describing the concept of the album. So, Marduk could be black metal, but also Danzig, I guess, because of Lucifer and Satan. That was the defining element. It wasn’t until ’95 that people started naming bands ‘black metal’ after how they sounded, and how they looked. Which was absurd to us, musicians saying, ‘We’re a black metal band because we wear corpsepaint.’”

Bjørnson speaks with Decibel two nights before Enslaved celebrate their 25th anniversary in Bergen, Norway. Less than a week later, they’ll play three different sets in three consecutive nights in London, each evening dedicated to a different chapter of the band’s history. Over the last quarter-century they’ve eagerly expanded their sound, inviting progressive influences while stockpiling Norwegian Grammys. After co-forming the band when he was only 13, Bjørnson never felt external pressure to keep Enslaved’s sound tethered to the primal charge of Frost and Eld—their “Frost and Fire” era, according to the anniversary event’s poster.

“Blodhemn was our last so-called black metal token, and we just felt that avenue was fully explored,” Bjørnson explains. “We wanted to explore more melodic, proggy, psychedelic aspects as a band. So, it was more like after the fact we realized that people were going to react to this, and see it as our final farewell to that pure Norwegian sound. Sure, we’d hear people hoping they’d get a Frost: Part II or whatever, but we were pleasantly surprised with how people reacted.”

Bjørnson’s music outside of Enslaved ventures even further from black metal. With Skuggsjá he creates complex, historical post-metal with symphonic grandeur. In April he’ll be in Brooklyn for the North American premier of BardSpec, his ambient project. But if his adventurous approach to songwriting raises eyebrows anywhere, it might be within his own band.

“To be totally honest, since I do write the songs in [Enslaved], I’ve felt people in the band might have wished for things to be simpler sometimes,” Bjørnson admits. “Or maybe they wonder if the band could be more successful if we skipped the experiments and weirdness. Maybe it’s egotistical, but I’ve always said that the songs just need to be how the songs are.”

ARKTIK EXPEDITIONS

It’s sunny outside Ihsahn’s home as he speaks with Decibel, but snow is headed toward Notodden. During the days that follow, the snowfall turns out to simply be a dusting; nothing like the moonlit ice kingdom adorning Emperor’s In the Nightside Eclipse, and worlds away from the unforgiving terrain traversed by Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen.

At the close of the 19th century, Nansen began a dangerous trek to the North Pole. Braving the elements—blizzards, lethal temperatures and belligerent walruses—he survived off limited supplies and the meat from his own sled dogs as the expedition waned. While Nansen didn’t achieve his lofty goal, his determination and bravery inspired Arktis and the album’s art design.

“[Being a musician] is far less dangerous, at least physically,” Ihsahn laughs, comparing Nansen’s travels to his own journey. “Nobody had reached the North Pole at that time, and he didn’t end up reaching it himself, but he spent three or four years trying. The Arctic in itself is absolutely beautiful, but at the same time it’s such a hostile, cold, harsh environment. But [Nansen] still pursued his goal with courage, enthusiasm, and excitement. I hope to remind myself not to settle for comfort, and always move forward.”

Ihsahn tracks his artistic progress all in the same ordinary, hardback sketchbook he’s kept since his first solo album, 2006’s The Adversary. Within those pages he has notes for every single song written under his own moniker, clearly illustrating his departure from black metal to Arktis’ playful, hard-edged pop sensibilities. Whether it’s his own eclectic solo work or shifting Thou Shalt Suffer from death metal to neoclassical arrangements, Ihsahn is controlled by nothing but his own instincts and whims.

“I’m asked when I do experimental records, ‘Aren’t you afraid you’re going to disappoint fans or lose fans?’ But I think I’m here doing this in the first place because I never really made music to please any fans,” Ihsahn argues. “A black metal band in 1991 was trying to displease everybody. It has never been a quest to be popular; it’s always been about being completely uncompromising.”

Outside his own music, Ihsahn also tutors music students two evenings a week. He doesn’t consider it his place to lecture students about his own artistic philosophies, only to encourage their own musical passions. “So many of my students are there because their parents arranged it, and they’ll say, ‘Sorry I didn’t do my homework this week, I had so much to do with football or whatever.’ And I just tell them I don’t care,” Ihsahn shares. “There are so many things in life you have to do, but playing guitar isn’t one of them. Making music is something you do because you love it.”