When interviews for the Hall of Fame piece celebrating Flotsam and Jetsam’s Doomsday for the Deceiver (which appears in the December 2021 issue, available here) were being organised, guitarist Michael Gilbert was the point man between Decibel and the ex-members who played on the album, including former bassist Jason Newsted. You may have heard of Mr. Newsted and some of the other bands he’s played in (namely Voivod and that other one). In connecting us with Newsted, Gilbert gave us a heads up about his former bandmate being “like an elephant” in that he never forgets. Initially, this was to reassure us that he wouldn’t flake once an interview time was locked in. What Gilbert’s heads up failed to mention was that Newsted doesn’t just forget agreed-upon interview times, but how he also hasn’t forgotten anything from his past, just how deep and thorough those recollections are and how much he enjoys sharing those details.

When a Hall of Fame story shows up in an issue of Decibel, space considerations limit each piece to somewhere in the neighbourhood of 5-7000 words (though I’m admittedly one of the worst word count offenders, as I’m sure Albert will tell you). Our interview with Newsted about his time before, during and slightly following Doomsday for the Deceiver ended up being so fraught with minute details and awesome stories that his portion of the piece alone would have been the entire piece two times over — even taking into account he’d already left for Metallica by the time Flotsam started playing shows and touring in support of Doomsday. So, with the space provided by the internet and this webpage, we’re running a full transcription of our interview with Flotsam’s founding member and former bassist as he takes us through the story of how a starry-eyed, but ruthlessly hard-working (and gear obsessed!) kid went from humble beginnings to creating one of thrash metal’s most popular albums and playing in one of the biggest bands in the history of music.

As the story goes, you ended up in Phoenix after the band you were in broke up on the way to Los Angeles and Flotsam and Jetsam was formed shortly thereafter.

When I was 18 years old, in the autumn of 1981, I was in a band in Kalamazoo, MI, where my family is from, called Gangster and there were two other members who travelled with me. They were 26 and 27 years old; the guy that taught me guitar, his name was Tim Hamlin and he was driving the U-Haul. It was him, his girlfriend, the other guitar player and myself with their sheepdog in the back of the U-Haul and we were headed to Los Angeles to be rockstars. I sold a bunch of my record collection, I had my Gibson Ripper bass and a Sunn O))) bass amp with two 15s in it, a suitcase, $300 in my pocket and we made our way across the country. We were pulling a late ‘40s Dodge panel van behind the U-Haul, so our top speed was about 47 mph and going all the way across the country took some days. We maybe stayed in one hotel on one night, otherwise we’d sleep in the truck or wherever we could. It took about five or six days to get across the country. We came down into Flagstaff, Arizona in the last week of October and it’s pretty cold in the desert hills when the sun goes down, so we decided to drive south down into Phoenix and we landed at 55th and Glendale in Glendale, AZ right outside of Phoenix. We parked the U-haul in an Alpha Beta parking lot for a couple of days trying to get our bearings and figure out what we were going to do, whether to make it to California or to stay where we were. We decided to stay. We put all our money together, rented a house right in downtown Phoenix, which you probably couldn’t do today. It wasn’t very developed back then. The city only had one major building on Central Avenue; it wasn’t even really a city yet, it was just desert. We stayed there a few days and I got a couple jobs right away. I got two different jobs within the first two days we were there: washing dishes and working in a pizza place. I did that for about three or four months when I went to the local music store at Indian School Road and 16th Street in Phoenix and was just looking around and dreaming about the guitars on the wall like you do when you’re 18 years old and have four bucks in your pocket. On the way out on the musicians wanted bulletin board, [drummer] Kelly Smith had an ad that was looking for band members for a band in Scottsdale that played Rush, Iron Maiden and someone else. I took his number, went and found a phone — we didn’t have a phone in the building we were staying and I did a lot of payphone stuff back then — and called Kelly. I set up a time to go out there, borrowed my girlfriend’s blue two-door Maverick that I could push the seat up and still fit my Sunn O))) cabinet in. By the way, that’s the measure of any good vehicle: if you can fit an SVT in it. Any vehicle I’ve ever purchased or rented or borrowed, if you couldn’t fit a SVT in it, it’s not worthy.

I hear ya! It was partially why I lamented having to get rid of my Pontiac Sunfire back in the late ‘90s [laughter].

Absolutely! So, I’ve got my cabinet in the back of her Maverick and rolled out to Scottsdale. I lived in a pretty crusty part of Phoenix at the time — 16th Street and Campbell, right across from strip clubs and that sort of vibe. I drove out to Scottsdale, 70th Street and Oak, I think, where Kelly’s dad lived and it was pretty macking out there. There were nice houses, people with a couple nickels had thrown them together and it was definitely different from the ‘hood I just drove from. I had my bass and loaded my stuff into the back room of Kelly’s dad’s office; it was kind of an addition to the back of the house off the swimming pool with sliding glass doors. I set my stuff up and there were three guys in there: Dave Goulder, who had a fucking Gold Top Les Paul, man! I couldn’t believe it and that I was standing in a room with someone who had one. It was a proper ‘70s Gold Top, maybe older, and now I can’t imagine what that’s worth. He had a nice amp, but he couldn’t play too well. But he had cool gear. Another cat was named Pete Mello, which is a great name for a rock guitarist, and he had the Eddie Van Halen style Kramer; I think it was even red and he was a lot better and more accomplished player. He didn’t have a whammy bar, but he’d still do the dive-bombs and bend the neck off the body and it would go out of tune and shit and that was his thing. And then there was Kelly and his drum set was from here to over there; it was like Neil Peart, dude! He had toms all over and no skins on the bottom heads and all angled up at him. It was this friggin’ rock drummer guy all tucked over in the corner of this office. He took up a lot of space, but he was good, even back then. He’d put in his hours listening to and playing along with Rush. He was way ahead of me as far as complexity and figuring out the forms and stuff. So, we just started hitting some stuff. I brought in one or two originals. I can’t remember if we ever talked about doing covers, but someone would hit a riff, we’d beat the piss out of it for three or four minutes and then move on to the next thing just trying to make some sort of noise. I remember I took a riff in that I stole from Riot; I called it “Luckless” but it was taken from this song called “Road Racin’” from this live at Donnington recording that Gangster had that we would play the shit out of. That was the first ‘original’ I ever played with Kelly. We hit it off pretty well and I went back whenever I could. The next few weekends we would hit it and I think Dave Goulder got phased out a little bit and Kelly or I would bring in different guitar players. We first played on February 10th, 1982; that was the first time I went over to his dad’s house and then we rocked through those months and I kept working both of my jobs. Kelly was probably 16 years old and was still going to Scottsdale High School and I was just about to be 19 in March of 1982 and the other guys were probably 17 and at the beginning we called ourselves Paradox. Then, we changed the name to Dredlox because we liked the way the word sounded and because it had the word ‘dread’ in it which we thought was heavy metal scary. We were so fucking unworldly and ignorant that we didn’t realise that dreadlocks were what they are [laughs]. We didn’t have any fucking idea about Bob Marley or Rastafarianism and what any of the meant. We were just these really, really white kids. I remember we got this one gig which we thought was going to be a real gig. They let us play on the football field at Scottsdale High School. Somebody set up a stage and the guitar players had these little bitty combo amplifiers and we didn’t know anything about miking up amps or how to use a PA or anything. We thought we were all cool and when we went to play, there were two people on the field: one girl that I talked into to coming to watch and someone else. I remember walking out of that back janitor’s room to go out and play and the janitor guy says, “Oh, Dredlox. So, you guys play reggae?” We’re like, “Huh? What’s that?” So, we go out and try to play and we’d get through half a cover of a Tom Petty song or half of “Breaking the Law,” half of one of my originals and after the first minute-and-a-half it would putter into nothing. We had this guy singing, John Eurich who was a friend of ours whose dad owned a strip club and I was a bartender there. He had long blond hair and wanted to sing, so we gave him the microphone and he went up there and was about as good as the rest of us. That was our big debut: playing at the full football field with two people sitting there and there was no way they could hear anything but noise blowing around. I think the singer quit after that ‘gig,’ if you want to call it that.

Goddamn, man, that’s fucking hilarious! [Laughter]

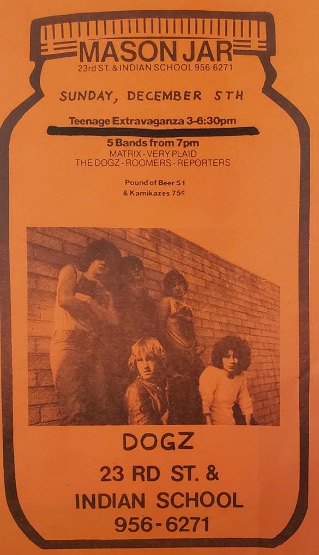

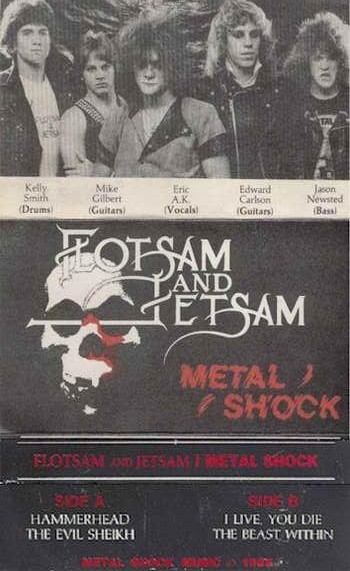

So, there were two other cats in the neighbourhood in Scottsdale: Mark Vasquez was a very gifted, natural musician. He was a great guitar player in general, but he could soak up every bit of every one of those records we played the shit out of — Unleashed in the East, Killers, Ace of Spades, Filth Hounds of Hades, British Steel and those bands that taught all of us in that era. He could play every fucking thing off of every one of those records. He’d just soak it up, never took a lesson, never read music, he was that guy and we were lucky enough to have him for a couple of years. Him and Kevin Horton, who was a neighbour two blocks down, were already buddies from school and they learned guitar together. Kevin was the sort of guy who was six-feet tall when he was 16, he had a cool Stratocaster that he modified and a nice amplifier. Mark had whatever he could come up with, but he could kill it with whatever he used. He was a real natural and I regret still ever parting ways with him in a band. Mike Gilbert was an absolute blessing and is wonderful and has flown the band to the place it is now, but Mark was really, really gifted and I often wonder what would’ve happened with Flotsam if he had stayed in. We got some songs and a repertoire together and we got gigs and played keggers and house parties and kitchens where all of us were plugged into one outlet — all of that good stuff. It was myself, Kelly, Kevin and Mark and we called ourselves the Dogz. We developed quite a reputation; we played desert parties like you’d hear about desert sessions from Kyuss and all that. Well, we had our own desert sessions back in ’83 and ’84 where we’d rent a generator, set ourselves up, someone would bring a keg and you’d let people know. We did a handful of those and I think that’s where we really cut our teeth. We had some hardships and some fuckery, but we kept going with the same members. After we got a little bit established, Kelly came across Erik A.K. He was singing at a talent show at either Coronado or Scottsdale High School — all of the band members went to either of those schools — and he sang “Goodbye Girl” and was fucking amazing, even at 17 years old. He’s a fantastically, naturally gifted person. He was given an incredible gift and his parents nurtured that. He came from a family of theatre people who encouraged theatre work and that was a real blessing for us. Erik came in and we wanted to get more metal so we started to have some personal things go with the guys from the neighbourhood. Then, Mike Gilbert came into the picture. We met him at the Scottsdale guitar store. He was 16 and a little tank of a guy who was really involved with his health, physical fitness and keeping his muscle tone up and all that and he still pretty much looks the same today [laughs]. He came in with his black Gibson Flying V and he’d only been listening to Slayer, Destruction and shit and he was a full fucking shredder and really impressed us in the amp room of Neil’s Music in Scottsdale. We closed the door and he played for Kelly and I and we just looked at each other and said, “Fucking A!” By himself, he was crazy and shredding and that’s what we were after at the time. I don’t think he was as naturally gifted as Mark was at the time, but he flashed us with the speed and dexterity and he had nice gear. So, he got in and we became Flotsam and Jetsam in there somewhere. We had a pretty good following around the area, like a 20 mile radius around Phoenix, and I remember having to put on the flyers “formerly the Dogz” as people were catching on because it was a left field kind of name back then. It was a good name though; I’m glad we chose it and it turned out to be really great. We wanted it to be like Misfits, Drifters and all these sorts of different names we tried out that were already taken and Flotsam and Jetsam was cool because it meant all of those things. We went on with that, got a little bit bigger, got some good gigs opening for Surgical Steel in Phoenix and the surrounding area and a couple of our own headlining things. A Battle of the Bands got us eight hours of recording time at a studio called Charton in Paradise Valley which was run by the guy from the Schoolboys, Danny Wexler, which was the biggest Phoenix band at the time. He had us come in there and that’s when we recorded the Metal Shock demo which I started shopping around. I was doing all the correspondence and tape trading and soon as we had the demo available, I was on that. So, people knew about us in a bunch of countries by the time we did our second demo and it really hit well. That put us in a place where we were feeling good about ourselves and I was really motivated. In Phoenix, you work from four in the morning until one in the afternoon because it’s 110 degrees by noon so you want to be done with that shit. So, we’d have the whole afternoon and night to work on the band and that’s what I did. I’d get up early, go do landscaping and other shit in the sun and come back and work on building the band up. I finally got the attention of Brian Slagel from Metal Blade. It was Kevin Horton who drove me out to Los Angeles in his cool-ass white Camaro to meet with Brian.

So, at that point, you hadn’t actually played in LA? Were you mostly opening for bands that were coming through Phoenix?

We’d only ever done Tucson, Phoenix, Paradise Valley, Tempe, Mesa…that little radius. We were the go-to band to open for whoever was cool that was coming through and not playing the arena. Mercyful Fate, Exciter, Yngwie…all those bands that were touring at that time we would open for. That was really good for us because the world of mouth went around about us and when time came for Flotsam stuff, or even Metallica stuff, I’d already had contact with all these bands because I was trying to run the show, fly the flag and be the leader and all that. So, I was the guy who was the contact for all the gigs. So, we go to L.A., meet with Brian, he gives me a contract which I take back to Arizona, make a few amendments — whatever my little 19 year-old high school drop out legal knowledge brain came up with — and we got going. We rehearsed as hard as we could, got our shit loaded up on a U-Haul pulled behind my Ford Ranger truck and we went in three vehicles across the desert to Los Angeles, met up with Brian, went into the studio with Bill Metoyer.

Was it a given that you were going to record the album in L.A.?

That’s how we did things back then. Brian was racking up five, seven or nine bands a month at that time and he’d take Bill Metoyer into the same studios, get deals with equipment and they’d knock them out for how many hundred bucks a session. It was really up to the bands to earn their individuality. We were very well rehearsed. I ran the band like a fucking dictator. We rehearsed every day, maybe there was a five-day week here and there, but we played as much as humanly possible and we got that shit tight. I would get very upset if someone was late to practice. I was really neurotic and really insistent and kept standards really high and consistency and there was choreography like the Scorpions, man. We took all of the elements of all of our favourite bands. I haven’t mentioned Scorpions yet, but they played such a huge part in what we felt was cool, what we felt looked cool, the sounds, the production of their albums. I had been into the Scorpions going way back and they were a huge, huge influence on any good metal band in those years. The Blackout album was gigantic for so many of us and we wanted to emulate them. So, we worked through that stuff and worked out choreography and some crazy shit and I was insistent. I probably had a little rift with just about everybody because of my self-righteous attitude about having to do things a certain way and the only way we were going to get past those other guys was doing it this way. I know AK and I had a couple of some pretty bad stand-offs, but it got us to where we got. So, we got that deal with Brian, we went out with Bill into the studio for six days from beginning to end. We all shacked up at a hotel just off of Franklin and Hollywood. There was quite a little incident that happened on the one night we had off. They had to do some mixing or whatever and we had two or three hours that night to go out in Hollywood as a band. After all the pictures and images and stories that we would have imagined in our minds, we went out together. I had my leather jacket on and thought I was so cool walking around Los Angeles with my boys and all that. We went to the Troubadour and I had maybe a drink-and-a-half and I was feeling pretty good. We had also shared some mushrooms and those of us who partook were having a great time tripping balls around Hollywood. It was our first time being amongst all the lights and the hair and the girls and the mini-skirts and all of it and we weren’t just reading or hearing stories. So, we’re making our way down this alley behind the Troubadour heading back towards Sunset and these cops from the Hollywood sheriff department go by the alley as we were kind of running by. They thought we were running from them and, just like in the movies, they come beaming down the alleyway and stopped and searched us. We looked a bit suspicious; we weren’t entirely clean, we all had crazy-ass hair, ripped jeans and leather jackets and shit. The guy pats me down and finds the empty mushroom bag in my front pocket. There was just a little bit of dirt crust in the corner and it was nothing; we would have eaten it if it was worth it. It was nothing and I probably stuck it in my pocket instead of littering. The cop’s like ‘What do have here?’ They cinched me up, put me in the back of the car, took me down to the sheriff’s department on a Saturday night! I’m all trim, tight clothes, long curly hair, so I’m already pretty fucking nervous, plus I’m already out of my head tripping. So, I spent the night in the tank. There was one huge dude in there who had long hair and stuff and he had heard of our band. I basically tried to stay up all night and hang out, talk and stay as close as I could to this dude so if anyone came around or started any hubbub or confrontation, he was there. Brian Slagel came down, figured out the bail, got me out and we went on to record the record and finish it. That was a very surreal type of trip, especially for someone who’s always tried to keep his nose clean and do things right as the first one in last one out kind of dude. So, me being the one who got nicked, as the band leader or whatever, it was a weird thing, man. We got back to Phoenix, started putting everything together for the record, like promo, thinking about a tour and I really got on the case about the tape trading and got the recording out to everyone possible and got reviews from everyone I could that existed. Once that got going, the record had only been out a few months, then Cliff was killed. I never got a chance to tour that record with them, aside from the local Arizona shows we played; the victory shows, we called them.

What’s the story behind the album’s cover art?

It was Kevin Tyler who was a friend of a friend. We gave the idea to a couple of different artists who were in our circle. We all gravitated to one another and there were always a couple of metalhead kids who were good with a pencil, so the two we knew, we got the idea to them. My idea was that if you look at the title and the lyrics to “Metal Shock,” it’s about evil forces being defeated by the good forces of metal. That was my tongue-in-cheek concept and we took inspiration from Eddie and having a mascot. As far as the Flotzilla, we came from the desert where there was no water and we had this creature that came from the sea, so I don’t know how the fuck that happened [laughs]. But yeah, it was an idea we conveyed to the artist and we went along step-by-step as he put it together. It would have been based on “Metal Shock” and “Doomsday for the Deceiver” was the follow-up; it was like a two-part story.

When the Metallica thing happened, what was the mood like in the band? I imagine it was a bitter-sweet thing where everyone was pissed you were leaving, but it was Metallica and if any of the others hand the chance they would have jumped all over it.

Yes, it was mixed emotions, of course, and you nailed it because any one of the five of us would have taken the opportunity and the rest of us would have been a little bit bitter, but also thankful and proud and victorious in a way that one of us made it to that big level. You have to remember — and this is me being factual, not arrogant — that I put every waking moment into that band. Every single thing, every single stamp that ever got licked for something that got sent, every penny for every t-shirt that was made, all of it. I tried to head it all up and show by example. I would pick up everything I could from every person we corresponded with, every band I listened to, the bands we traded demos with, all these things. I had ideas of how we could be, what I wanted to be, I had a vision about it and taking the catalyst, motivator, generator, whatever you want to call me, out of the equation was going to be tough. It was very similar to what Lars had done in Metallica; he was always the leader who made all the calls, talked and wrote to people to get them to where they were. So, my stepping out left not just a giant void not just as a bass player, but as all of those other things as the leader. I remember specifically we would go into our practice room and we would always line up to practice like on-stage style — we didn’t know about playing in a circle and looking at each other when we were building a song. We always set up like we were performing a show every night and we would go from song to song to song and do it exactly like we would do it at a show. I had written on a manilla folder that was stapled to the wall the “rules” and it was something like ‘Consistency,’ ‘Clear-mindedness’ and a couple other things I put on there that everybody had to adhere to. It was like keeping the kids in line at school sort of shit, but it was also meant to be encouraging at the same time, something to maintain when we caught some momentum so that we were ready for the next step, and the next step which would be even bigger. So, all that ‘play right, do right’ stuff was written there and it would have been the first rehearsal that I came back to after I had been asked to join Metallica and Erik had written across the bottom of it, “Go join someone else’s band.” That got to me and I understand his feelings towards me and the loyalty and all that, but the world is the world and everybody is working towards a certain thing where they have their own goals individually and collectively. So, that was pretty heavy. I remember playing my last show with them. It was a great show, lots and lots of people because we had gained quite a following by then. We were wearing black armbands that night for Cliff as it had been two or three weeks since he was gone. And three-and-a-half weeks after his ashes had been scattered, I was auditioning. The thing to remember is there was a certain team spirit that we all had in our hunger, figuratively and literally. Most of the other guys lived with their parents, but I was hungry a lot! But there was a hunger to be like Iron Maiden, a hunger to accomplish something, a hunger to have people see us play, hungry to get something out of it beyond $7 at the end of the month to split, like every band working their way up. We worked really hard, practiced really hard and tried to keep it as organised as I could as far photo shoots, doing our own little videos, getting in the paper. I would send out demos and bug the shit out of [A&R legend] Michael Alago until he was annoyed. I would send him a flyer of a show we were playing, a photo, a tape of a new song and be like ‘come see us!’ He was in Manhattan and we were in Phoenix and I didn’t know any better! I’d just be like, ‘dude, come on over!’ But he was very encouraging and ended up being a very important player in all of our lives. I was tenacious, which is the word the Metallica crew guys used to use to describe me; when it was time for me to hit the show, I was already sweating before we’d hit the stage because I was ready to fucking go. I was tenacious and relentless and not taking no for an answer and that’s what I did. The band always came first, I did everything I possibly could for us as a collective. And Flotsam ended up signing to a major label had the opportunity to and tour the world and all that stuff so I feel that by me making the move that I did, I felt I took them to the most serious level of potential one could possibly have. No one can say that if I had stayed in Flotsam that we would have definitely signed to Elektra before we got sick of each other. There’s no way to tell.

Given the divide between the level Metallica were at and underground thrash metal, how familiar were Metallica fans with Flotsam? How aware were people of where you came from?

The underground and deep cut listeners knew where I came from, but Flotsam was pretty much in its infancy as the record would have only been out for a handful of months at that time. There was a handful that knew, but for the most part, no. And it took a while for that to come around. It took a while for them to put a sticker on the Doomsday record that said ‘Featuring Jason Newsted from Metallica’ and I do remember that the record ended up selling a couple hundred thousand copies by the time I’d been in Metallica for a couple years. For a Metal Blade record, other than Slayer, to sell 200,000 copies was a pretty big thing. That feeling of accomplishment of selling that much — and it’s got to be close to half-a-million by now, if not more — is pretty good for a week’s long work by a bunch of thrash kids who had their shit together on one take drums and one-take bass lines.

Doomsday changed each of your lives in different ways, yours more significantly and publicly than the other dudes. What does the record and its legacy mean to you?

I think it was initially getting the approval and acknowledgement of our hard work from Brian Slagel to want to sign us and put money behind us and to take a chance on us. He was taking a chance on a lot of bands and we were one of those. That’s where I would start because all of that work and sweat in the desert. During those years leading up to Doomsday there were times I was basically homeless where I’d live in our little rehearsal room and sleep on the drum riser in a rental storage unit with no air conditioning. And coming from that and then still working so hard on the band and still accomplished getting the attention of Metal Blade, and what it came out as. If I look back now to realise how fresh and rubbery how brains were to recall and execute those compositions that efficiently and effectively, that would be the thing that would be the shiniest part of the crown for me. We would play those songs and people would stand back and be like, ‘fuck, that took something. You just don’t get that by hoping you can get that.’ That came from a lot of hours together and a lot of hours of one guy being a little shitty, making sure everything was perfect as we can get it. From me getting the not-always-so-great feelings and reactions from the guys because I was always nagging because I wanted it to be as good as could be and I wanted everyone to want it as much as I wanted it. And I think I got it to that place where everyone was committed to it and to find that in a band is really fucking hard; to have everyone on the same page about putting in the time and having everything else be second to the quest – that accomplishment in itself of five 20 year old freaks all doing their discovering of drugs, girls, booze all at the same time and still maintaining being able to play those songs that good at the drop of a hat with not an inkling of ever trying to cheat in any way or hoodwink a fan or listener. We could do everything we said we could do — before there was ProTools, there were pros, man. That would be the greatest part of the victory. It was great to have the record and I still enjoy to this day when I hear it now and again, and it’s fucking awesome for a bunch of 20 year old kids. It’s amazing accomplishment because of the physicality and the mindset. It’s hard to get everyone on the same page about anything when you’re young guys.