Converge will perform their seminal metallic hardcore classic, Jane Doe, in its entirety at Decibel Magazine Metal & Beer Fest: Los Angles on Friday, December 10. Tickets for the exclusive performance are still available, but are moving fast (tickets for their Jane Doe set at the Philly edition of Metal & Beer Fest are already sold out)!

In the time between acquiring tickets and waiting for your chance to down bitters and then some during the New England legends’ landmark set, you can celebrate the 20th anniversary of the album and dig into the full Jane Doe Hall of Fame from our long sold-out January 2008 issue and Precious Metal Hall of Fame anthology. Previously unavailable online, the following story features lengthy interviews with every member of Converge who performed on the record.

Inside a Freeform Mathcore Maelstrom

Call it the face that launched a thousand metalcore graphic designers (into a rat-race of feverish mimicry). Call it the record that catapulted a certain Boston quartet (then quintet) into permanent cult status with a slew of face-ripping live staples (“Concubine,” “The Broken Vow” and “Bitter and Then Some”) and a soaring, epic title track. Call it Album of the Decade, like we did in 2009. Any way you break it down, Jane Doe was both a semi-melodic milestone (“Hell to Pay,” “Thaw,” the title track) and a discordant landmark (everything else), far and away the most crucial metallic hardcore record since fellow Massholes Cave In (who had since stepped bravely onto the major label playing field) unleashed Until Your Heart Stops three years earlier. Shit, it even had a song that was just drums and vocals (the 42-second apocalypse of “Phoenix in Flames”). It was feral, it was ferocious, it was fucking unstoppable. And it’s still all those things today.

It was also 2001, and change was everywhere. Bassist Nate Newton, formerly of Jesuit, had joined the band three years earlier and recorded on two split releases—1999’s The Poacher Diaries (with Agoraphobic Nosebleed) and 2000’s Deeper the Wound (with Japan’s Hellchild), the inaugural release from Converge vocalist Jake Bannon’s label, Deathwish, Inc.—but had yet to track a full-length with them. The band had also recently recruited local drum dervish Ben Koller, formerly of grind outfit Force Fed Glass, to replace skinsman Jon DiGiorgio. By the time the Jane Doe recording sessions—a three-month marathon spread across as many studios and helmed by Converge guitarist/producer Kurt Ballou—were complete, the band had kicked longtime second guitarist Aaron Dalbec (also of Bane) to the curb. On September 1, Ballou was laid off from his job as a medical engineer at Boston Scientific (“it was like the adult version of playing with Legos”), thus freeing Converge to expand considerably upon their annual one-month touring schedule. On September 4, Jane Doe was released to considerable critical and popular acclaim. On September 11, the day the band was to embark upon a two-week tour with Playing Enemy, the Twin Towers fell and the world changed forever. Converge—now a sleek and furious four-piece—drove into New York City under a blanket of ash, on the road to a silver future.

PART I: PHOENIX IN FLIGHT

What do you remember about the songwriting process for Jane Doe?

Kurt Ballou: It was the first batch of song we wrote after Ben joined the band, so we definitely had a new perspective and a new energy and a new means of working. And Nate was also finally living in Boston—prior to that he was commuting up from Virginia. And we were all on the same page musically. We all had a lot of respect for each other as musicians and friends, so that was the first record we wrote that was really a collaborative process. I’d always been a control freak prior to that—in a way it was because of who I am, but in another way, it was also because I’d had to because I didn’t have people in the band who could contribute well until Jane Doe. Aaron was doing a lot of Bane stuff—they were really busy that year. They were doing a record and a ton of touring, so he wasn’t really around for much of the songwriting. It was pretty much just the four of us hacking through the songs together.

Aaron Dalbec: I was on the road a lot with Bane at the time, so I would come back to work on new songs with everyone, and when I would leave for Bane tour, I would be writing while I was on the road.

Nate Newton: I remember a lot of butting heads, between me and Kurt especially. That was the first record where I was really part of the songwriting process. I played on The Poacher Diaries and the split with Hellchild, and I had written a little bit on The Poacher Diaries, but that was a weird time, because Jon [DiGiorgio] was only in the band for a really short time on drums and we never really got acclimated to playing with him. I felt like a lot of those songs were just kinda hammered together really quickly. So Jane Doe was the first time I wrote full songs for Converge. And it was the first time Kurt had someone telling him, “Hey—I don’t like what you’re playing.” I don’t think there was much of a filter before, mostly because Converge wasn’t as busy of a band. One of my focuses was that I wanted to write songs—I didn’t want just a shitload of riffs piled on top of each other. I was really critical of what Kurt was writing, and ultimately I think that was a good thing for us—it taught all of us to be more critical of ourselves.

Ballou: The other big that happened with that record is that for “Minnesota,” the last song on The Poacher Diaries, I had invented a new tuning that I had used for all the lead guitar parts. I ended up being really inspired by that tuning and used a lot of it to write a lot of the Jane Doe stuff. It gave me a totally new perspective and new harmonic structures. All the happy accidents you have on guitar when you’re tuned one way—even though they might be physically similar—they sound completely different when you start tuning a different way.

Ben Koller: I remember being very impressed by Kurt’s demoing skills. He demoed all the music himself for the song “Jane Doe.” It’s just such an epic, memorable song and we didn’t deviate too much from that demo when we recorded it. I remember being very impressed by that demo. “Phoenix in Flames” was fun, too. I was half-joking one day at the studio, like, “We should just do a song that’s drums and vocals only.” I can’t believe we actually put that on the record. I love that song.

Jake Bannon: I can only speak for my own experiences with the album. Life wasn’t going all that well for me and I saw writing and rehearsals as an escape of sorts. I looked forward to that few hours a week more than anything at that time in my life. It was also an odd time for the band. Getting to practice wasn’t easy. It was a half-hour to an hour commute each way for all of us. Because of that physical distance, it didn’t feel like there was all that much communication between members. When we did get together to write, it felt like three of us—Ben, Kurt and myself—bonded a bit more than we did with Aaron. That growth between us as friends/family foreshadowed a great deal for all of us. As a band and as people, we were evolving.

How did you meet Ben?

Ballou: I recorded two of his previous bands. The first one was called Bastion—not too many people knew about them—and the second one was Force Fed Glass, and they were somewhat known. He and I started playing together in a thing called Blue/Green Heart that was kind of a short-lived side project. When Jon DiGiorgio, the previous Converge drummer, quit, it happened really suddenly. I think I actually found out about it at Blue/Green Heart practice. I was talking to Ben about it and we just started jamming some Converge songs. At the time, we weren’t really sure if he could do it because he couldn’t play double-bass, and at that time Converge had a lot of double-bass stuff. So originally he played as a fill-in and we tried out some other drummers, but it became pretty clear pretty quickly that Ben was the guy.

Newton: Ben joining the band made Converge who we are now. I have no doubt in my mind that we would’ve broken up if he hadn’t joined the band. His drumming is such a big part of the direction that we went with this band, because songwriting-wise, we were never able to do what we wanted to do. He’s got his own style, and it’s punk as fuck. We were so excited about him joining, and you can hear it in the record. There’s such a huge difference between that record and the ones that came before it. Sometimes when we’re onstage, I’ll turn around to watch him play and just think, “Fuck—you are so much better at your instrument than I am at mine.”

Jane Doe was your first recording with Ben on drums and your first full-length with Nate on bass. Did you feel invigorated by the relatively new lineup? Were you nervous about the potential results?

Bannon: Both of them brought a new energy to everything, and I am still grateful to them for that. For Converge, it was the first time that there was a “whole” band—or at least four of us—participating in the writing process. In the past, it was Kurt as the chief songwriter, and I handled everything else for the band. Though Kurt still was at the helm musically, with Jane Doe, Nate and Ben played significant roles in shaping the music to the album. I also contributed rough versions of the riffs in “Homewrecker” and “Phoenix in Flight” to the album. Though I am a terrible guitarist, Kurt managed to make sense of my mess and turn both of them into great songs. I know that all of us playing equal roles was an reinvigorating experience for me. I felt excited and I had a second wind of sorts creatively because of that.

Dalbec: I was not nervous about the lineup at all. We had been playing for awhile, and Ben was the first drummer since Damon [Bellorado] that really fit with us. As far as Nate, I loved playing with him. He is a great dude, and a great guitar/bass player. It added so much new energy to the band.

What were the recording sessions like?

Ballou: We did them at Q Division in Boston with Matt Ellard engineering. I guess I was producing—you don’t really have producers when you’re doing hardcore records. But I was the one who was there all the time presiding over stuff. Q Division has two studios and we booked our time in Studio A at a certain rate that was below their advertised rate. And then James Taylor came along and decided that he wanted Studio A during our time period. He was willing to pay the full rate, so they bumped us over to Studio B—which ended up being a blessing in disguise because even though Studio B is a little smaller, the room is a little brighter and the console is a lot more crisp-sounding. It’s a Trident ATB, which I actually have in my studio now—and part of the reason I have it is because of the drums we tracked on Jane Doe. But we went back over to Studio A after James Taylor left, and then we did the guitars, bass and some vocals at my studio in Norwood. We mixed it and did the rest of the vocals at Fort Apache in Cambridge.

Koller: I remember it being very laid back. It was a comfortable environment and there wasn’t a lot of pressure. I also remember James Taylor recording in one of the other studios and him being escorted in and out by his entourage. Why did he need to be escorted? Who cares about James Taylor anyway?

Newton: James Taylor was across the hall from us and he kept sending his engineer over to tell us to be quiet. “Mr. Taylor is trying to record vocal tracks and you guys are goofing off and being way too loud over here.” [Laughs] He had already knocked us into the smaller room, too—but that’s fine. I don’t really care.

Bannon: For me, it was the first time that we were in a more formal studio setting. Aside from the occasional weekend recording sessions at outside studios, we usually recorded on our own in some way. Even though the When Forever Comes Crashing album had Steve Austin at the helm, it was in a no-frills studio in a basement in Allston. At Q Division we had a engineers and assistants helping during the initial tracking. We had an English engineer who worked with Motörhead and George Michael giving us assistance and guidance. It all felt “important” and “special” to me. We were all working together and I really appreciated that.

Dalbec: I just remember it being the most well-organized recording we had ever done. We made sure all the songs were 100 percent before we recorded them. We had recorded the drums at Q Division, and we did most of the guitars and vocals at Kurt’s old studio in Norwood. That way we had more time to work on everything.

Newton: You know, I’ve never been a great bass player, and I’m well aware of that. But this was the first time that I was in a studio for a long period of time and someone was extremely critical of what I was doing. And I had a hell of a time recording some of those songs—like “Thaw.” That song is fuckin’ hard to play, and I would get really frustrated. But Kurt really pushed me, and I’m thankful for that, because I’ve learned a lot from playing with Kurt. He’s a great guitarist. And I’m not taking credit for anything because I’m just some douchebag who plays bass, but I will say that Kurt is so much better now then he was then. I’ve never really said this to him, and maybe it’ll make it to print and he’ll tear up a little bit, but I’m honored to play with him. I’m constantly blown away by the things he does. But I don’t say that when we’re writing songs, because I gotta show him who’s in charge. [Laughs] Which usually turns out to not be me.

Ballou: I did most of the guitars at my studio, which was in Norwood, MA, back then. It was really tough because I was recording myself and there was no one else in the studio, and everything for that record was done on two-inch [tape]. I sat with my shoes off and my feet up near the tape machine so every time I screwed up and had to punch in, I could work the tape machine with my toes while I played. And that machine would punch in, but it wouldn’t punch out—or when it did punch out, it made a click. So you had to wait for some silence to punch out or you had to play all the way to the end of the song. It was really, really laborious. I think Matt Ellard actually came down for a day or two to help me out with some of the more challenging punch-ins so I could be free to just play. Between starting recording and mastering, the whole process probably spanned three months. But it’s not like we were working the whole time. Jake lost his voice at one point and we had to wait a month to get another mix session. I remember I couldn’t stay for all the mix sessions because I was doing some Cave In recording—I think they were demos for RCA or something. After that we went to West West Side to master it with Alan Douches, and I think we actually banged that out in a day. Alan pushed it really hard. To this day when I see him, he still talks about how loud that record is and how people always come into his studio commenting on it or asking him to use it as a reference when mastering their record. So that’s cool to hear.

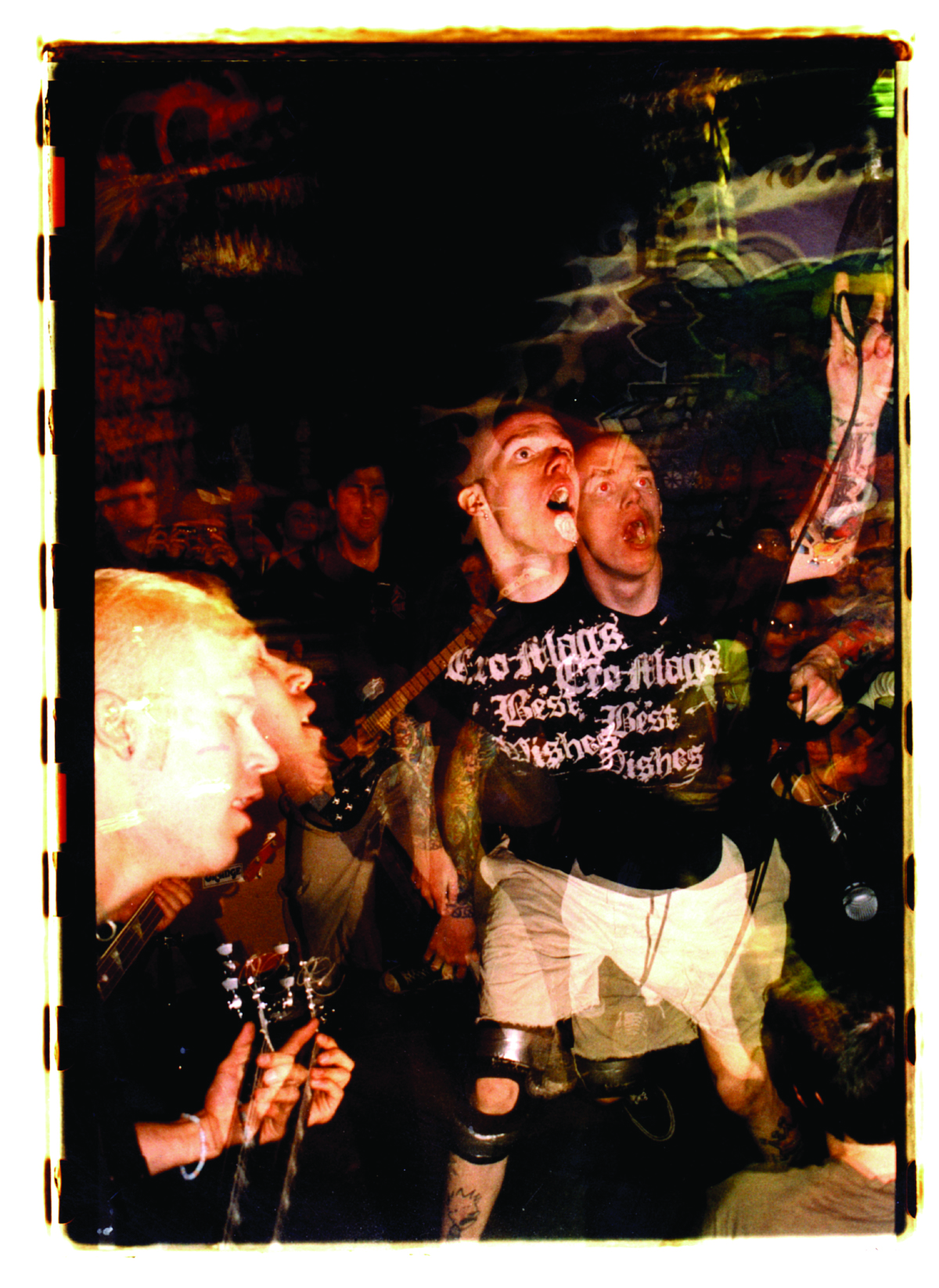

Bannon: Recording vocals was a surreal experience. Most of my tracking was done in the live room at Fort Apache. The studio used to host live recording sessions with audiences in the room, [so] it’s set up much like a venue. I was recording on an actual stage with no band behind me—I felt really exposed and isolated by that. I also recorded most of the vocals in the dark. Not sure why, really—I think I was just feeling shy, in a way. By doing that, I was able to just lose control and get all my negative emotion out of me on that stage, and on tape. I listen back now and I sound like a rabid animal in a lot of places. It’s definitely vicious. You can hear that real anger and emotion in there for sure.

PART II: FAULT AND FRACTURE

What was Aaron Dalbec’s involvement in Jane Doe and what were the circumstances surrounding his departure?

Newton: Ah, the big question… Well, Aaron was around for some of the writing process, but at that time, Bane was really taking off. They were way busier than Converge at that point. It got to the point where he was gone so much and we would have to turn down tours and show offers because he wasn’t around. Basically, if we wanted to continue as a band and do the things we wanted to do… Aaron just didn’t have time to be in Converge. To this day, I’m still not happy about the way everything went down, because I love Aaron and I think he’s a great dude.

Bannon: Aaron’s role in Jane Doe was quite minimal, as it was in all records. In retrospect, he was primarily a live guitarist more than anything. Though he would track on albums, his style of playing wasn’t that precise and didn’t come off well in a recorded setting. My memory isn’t the best, but the only song I remember him ever bringing to the table for Converge was “High Cost of Playing God,” which was released on the When Forever… album. He concentrated his writing for his band, Bane, which was much more fitting for him.

Koller: He wrote a couple riffs here and there, but he was pretty disconnected from the rest of us. We would have rehearsal without him from time to time—then he would come back from a Bane tour and he would have to relearn certain riffs. It really dragged us down. He just couldn’t devote his full attention to the band, and we wanted to push it to the next level.

Ballou: I’ll let him answer that however he wants to answer it. I mean, he had talked about leaving Converge before, and it was always Bane-related. Bane was his band and suits his taste in music. When he joined Converge, we were a different band and a much less active band. We didn’t really have the talents or tools to express ourselves how we wanted to. As we all progressed as musicians and songwriters, we progressed in different directions. I think Aaron was a little too stubborn to leave the band even though he knew it was right, so we kinda told him, “We’re gonna do this now, and we just don’t think you’re able to do this on the level that the rest of us wanna do it, and we don’t think you’re into this on the level the rest of us are into it, so it’s probably time for you to just focus on the band that you’re into.”

Dalbec: Well, pretty much the way it happened was I had just come back from recording Bane’s Give Blood record, and we got together to “talk” about our upcoming two-week tour when the record came out. At this point, it was about two or three weeks away. I got there and [was told] pretty much that I had to choose between Bane and Converge. Now, just for the record, Bane had never gotten in the way of Converge. It was always Converge first, then Bane. If Converge had a tour, Bane would not book anything—we would even wait for Converge to make plans before we would decide what to do.

As far as when I left the band, it was about two weeks before Jane Doe got released. So all the recording for Jane Doe had been long done.

Bannon: Matt Ellard, our engineer at the time, had Kurt play most—if not all—of the guitar tracks on the entire Jane Doe album. With that said, it was evident to the band and others around us, that [Aaron’s] role was becoming a larger issue that couldn’t be ignored. After playing an unannounced show with Isis in Cambridge, we called a meeting without Aaron and decided that it was best for him to step down from the band. The next day, the five of us, along with [Deathwish co-owner] Tre [McCarthy] and [former Converge roadie and current booking agent] Matt Pike, sat down and broke the news to him. After that, we did our first tour as a four-piece and loved it. We never had any drive to become a five-piece again.

Newton: Oh, man… the way we did this was so shitty. It was the night before we were leaving for tour and we had a band meeting. Everybody kinda sat down and explained stuff, and I think Kurt was the one who said, “Bane’s going this way, Converge is going that way. Bane is busy—it’s obvious that Bane is your band. A choice has gotta be made here, and we’re gonna make the choice for you. You’re in Bane.” We all knew that it had to be done—and I’m sure Aaron in his heart knew it, too—but it was really fuckin’ harsh. The whole situation fuckin’ sucked and I’m not happy about the way it went down, but it had to happen sooner or later. We could’ve waited, and maybe he would’ve made the same decision himself. Or maybe we could have posed the question to him. But it had to happen eventually. I’d say it worked out better for everyone in the long run.

Dalbec: I was not happy at all about leaving Converge. I had dedicated over eight years of my life to the band and gave as much as I could for that eight years, and helped build the band up to where it was at that point. I had worked through the thick and thin, through the times in the beginning when nobody gave a shit about us, but we still worked our asses off. So I was not too happy about it. Now looking back at it, though, for things to end the way they did, I am happier to not be a part of that. I mean, I was ready to leave for tour and kill it with Jane Doe coming out, and at the last minute before the record comes out, they tell me I have to choose between Bane or Converge—and to quote Kurt, “You need to choose between Bane and Converge, and I think you should pick Bane.” For someone to say that, there would be no way I would want to continue with them. Some people think I was stupid to say Bane, but when you are in that position, there is no other choice. I felt totally betrayed and let down.

Ballou: Dalbec only played one show on Jane Doe, but it was about a week before the album came out. We played a record release show upstairs at the Worcester Palladium—I think we had about 20 copies of the record. I remember because the record came out on September 4 of 2001 and we were supposed to start a tour with Playing Enemy on September 11, but we had a few shows cancelled because of the attacks. We drove through New York when it was still covered in dust. We were comfortable playing all the Jane Doe songs as a four-piece because we had pretty much practiced them all as a four-piece. But I remember we weren’t sure if we were going to continue as a four-piece or get another guitar player. After that tour, the benefits of the simplified lineup outweighed the benefits of a second guitar player. There’s more space onstage, more space in the van, more money to go around, and even though the stage sound might be a little less thick, a four-piece just seems more balanced. Live music can sound like shit, so you can hear the guitar more clearly if there’s just one. Some of the older songs ended up suffering, but when you’re the only guitar player, you can be a lot more expressive in your guitar playing without worrying about conflicting with someone else.

PART III: THAW

“Hell to Pay” stands out as very different from the rest of the record and very different for Converge at that time in general.

Newton: I guess it kinda was. I remember when I was learning that song—Kurt had written in it—it’s basically his Hoover “Warship” right there. I wasn’t that into it at the time, but in retrospect, it is pretty good. I did four bass tracks for that song. I had two amps and two basses and I played each amp with each bass.

Ballou: It was out of character for Converge, but not for our taste in music. You can hear in a lot of Converge records—going back to at least Petitioning the Empty Sky era, maybe even earlier—you can hear the Hoover influence, the Fugazi influence. You can hear me taking their ideas and trying to make them sound more metal. “Hell to Pay,” for example, is a combination of that and… I think I got into Jesus Lizard a few years before we did that record. So it was our way of doing that, but not trying so hard to make it metal. It gets a little doomy at the end. I think that song is one of the best vocal collaborations we’ve ever done, actually—definitely the best vocals I’ve ever done on a Converge song. Especially at the end, when it’s me, Nate and Jake switching off—it’s pretty cool.

It’s hard to imagine “Jane Doe” being anything other than the last song on that record. Did you know that it’d be the closer right away?

Newton: Yeah. It was like, “This is the one.” We were all really excited about it.

Dalbec: Yeah, when you listen to the record in all one piece it is very hard to imagine that song anywhere else on the record. When we were writing it, I knew it was going to be slow and brutal, but I was not too sure where on the record it would go. At the time, I had no idea what the lyrics would be like.

Ballou: I think we knew before we recorded it that it would be the closer. I can never remember how songs come to me. To me, songs are just gifts. I mean, I know they’re not given to me, but after I’m done writing them I usually have a hard time remembering how it came to me. I’m actually better at remembering what happened with stuff that other people write. With that song, I think I demoed it with a drum machine and showed it to the guys. It was much shorter at the time, and it didn’t have the ending. I remember thinking it might not even be a Converge song but they heard it and were like, “Oh, that’s awesome—we should use that.” So we did.

Do you have a favorite song on the album?

Ballou: I don’t know… “Hell to Pay” might be my favorite, actually. Or “Distance and Meaning”—two songs we never play. [Laughs] Stuff that sounds good live is not always what sounds good on record and stuff that’s fun to play live isn’t as much fun to listen to on a CD, unfortunately. I’ve kind of learned that throughout my entire musical experience, going back to playing jazz and classical on saxophone and clarinet when I was a kid.

Bannon: “Phoenix in Flight” gives me goose bumps. “Jane Doe” as well.

Dalbec: I really like “Fault and Fracture” and “Jane Doe.” [Those songs] just showed where the band was going, and it was totally new for us. I also really like “Homewrecker.”

Koller: Listening back to the record, I really like the song “Distance and Meaning.” It sounds very different than anything Converge had done previously. Some of the riffs were Huguenots riffs [a defunct Kurt Ballou side project] and I was a big fan of the Huguenots/SevenPercentSolution 10-inch… well, I liked the Huguenots side, at least.

Newton: I love “Jane Doe.” As far as the faster, more hardcore songs, I like “The Broken Vow”—and not just because I wrote it. [Laughs] It’s just a live staple, and it’s fun to play. I still really like “Thaw,” too.

Tre McCarthy, Kevin Baker from the Hope Conspiracy and “Secret C” have backing vocal credits. I’m assuming the last one is Caleb Scofield from Cave In.

Ballou: Yeah. He was under contract with RCA at the time. He didn’t think there would be any problem, but we thought it would be better not to take any chances. Isn’t his publishing company called Secret C? I think it might be. All those guys were on “The Broken Vow”—I think that was the only song they were on. On the last line, “I’ll take my love to the grave,” with each repetition of the riff, we’d add another person. So it’s Jake, me, Nate and then those guys, one at a time.

PART IV: UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE VICTIM

There’s obviously a distinctly female theme dominating the album artwork. What inspired it, and how does it tie into some of the lyrical concepts?

Bannon: At the time I was going through a great deal of negative in my life. When I was refining the lyrics, it was apparent that the album thematically dealt with that relationship disintegrating. The album was my lyrical purging of that experience. The artwork visually encapsulates that lyrical theme. The visuals attempted to capture the feeling of disintegration and rebirth. I spent a great deal of time on that—building figures out of texture and acrylic, scanning multiple layers of imagery, etc. I spent close to a month creating large mixed media pieces for each song on the album. I used a high-contrast approach to the artwork, as it was a style I was growing towards at the time. I felt that the cold iconographic feel was extremely fitting for the subject matter.

Was it your intention to obscure some of the lyrics in the layout, or did it just work out best that way, visually speaking?

Bannon: I wanted to incorporate them into the pieces themselves, so yes, it was intentional. I remember Equal Vision not being happy about it, as it broke from the standard that was set for the time. I don’t care much for rules.

Did Jake discuss the lyrical themes with the rest of you?

Newton: Not really. On every record, we just let Jake do his thing. We had a general idea, though. I actually thought of the name Jane Doe when were on our first European tour—I think I may have seen a pamphlet or a billboard about violence against women or some shit. I just thought it was a cool name. If I remember correctly, we talked a little bit about the idea of a nameless, faceless victim. Jake sorta took the ball and ran with it.

Dalbec: Jake never really discussed any of the artwork or lyrics with any of us. It was kind of always a surprise when the record was done.

Koller: Nate and Jake came up with the whole concept for the record, I guess. I don’t tend to get too involved with the art concepts. I just focus on the skins.

Ballou: He’s pretty private about that, and we don’t pry too much. He’s become more open with that over time, and at least with me, he’s gotten me more involved with phrasing and stuff. But circa Jane Doe, we just recorded his ideas the way he had it in his head and that’s just the way it was. There’s definitely a lot of mutual trust and admiration between us as songwriters. And whenever you have too many cooks in the kitchen, it tends to dilute the food. That’s how it is with a lot of modern metallic hardcore, too—there’s just too many ingredients in the mix. You’ve got your guy who screams, your guy who growls, and then you’ve got your melodic, Dashboard Confessional-style vocals here and there. I’ve always been opposed to that—I like to have a cohesive direction and a cohesive vision. So I don’t really get in Jake’s way too much and, in turn, he doesn’t get in our way, either.

About a year after the record came out, I was walking down Cahuenga Boulevard in Los Angeles with Juan Perez and saw a huge oil painting that someone had done of the Jane Doe cover. At first we thought it was Jake’s original, but we later found out that it wasn’t.

Bannon: Yeah, I heard about that. That painting was also a few blocks from our lawyer’s office in L.A. It was definitely a rendition of our cover, but it was meant to be an homage, not a lift, I guess. There have also been some other incidents. One high-end clothing company chose to use the image on a variety of t-shirts. They actually solicited my girlfriend’s old store to carry their items and she brought it to my attention. When our lawyer contacted them, they claimed they got the image from a poster they saw on a wall in Italy, to which I responded, “Yeah, our tour poster.” They later sent us their stock of apparel and I destroyed it. I’ve had that happen with other images I’ve made for other bands as well. The world is full of thieves. Since the release of the album, there have also been countless attempts at emulating that style of artwork. The attempts are both flattering and insulting. I feel that if you are putting that much effort into creating something to represent your band visually, you should do something original. Use your own artistic voice, not ours.

Newton: It’s interesting to me how the cover of that record—the Jane Doe face—has become almost iconic in the hardcore scene. It’s almost like the new Misfits skull or something—not that I’d compare us to that, but it blows my mind that we still sell a shitload of Jane Doe shirts. Go to a hardcore show and there’s a good chance you’ll see a kid wearing a Converge shirt, and there’s a good chance it’ll be a Jane Doe shirt. The face doesn’t call to mind anything specific, but at the same time, it’s a strong image that you can put meaning into. I think that’s what makes certain pieces of art powerful—you can look at it and put your own meaning into it. It seemed like during that time period, Jake and Aaron Turner really put the focus back on fine art back into album artwork—at least in this scene. It wasn’t just, “Here’s a picture of the band, here’s our lyrics, here’s our logo.”

PART V: PHOENIX IN FLAMES

Do you remember reading any reviews of the album when it came out?

Ballou: I remember we got Album of the Year in Terrorizer. I was pretty blown away that it was being received that way, actually. At that point in time, we were a band that had had some moderate success—people liked us, and we never really did support tours—we had been able to tour the U.S. a few times on our own as headliners. But I didn’t really feel like we had done a record that was a milestone in our genre. People consider Petitioning the Empty Sky that, but in general, the people who revered that record highly, I didn’t revere their taste in music all that highly, so it didn’t mean a lot to me. And it’s not even an album, really—that originally came out on seven-inch. And then we recorded extra songs and put it out on CD. There’s live tracks, too—it’s really just a collection of stuff.

Newton: I remember the Terrorizer review that came out before they gave us album of the year. I felt pretty good about the record, but when I read that I was like, “Whoa!” Not that Terrorizer is the be-all, end-all musical judgment, but I remember thinking of it as a magazine that tears everything to shreds. I think they gave us a 9.5—it was a pretty big compliment.

How did things change for Converge after Jane Doe came out?

Ballou: Jane Doe was the first record where people I really respected responded positively to it—people my age and older than us actually started to respect Converge. That meant a lot to me, because prior to that, I felt like we hadn’t really come into our own yet. People definitely treat you differently when you do something that they enjoy or respect musically. We got a lot of opportunities from the record label, booking agents were more interested in us, other bands were more interested in getting us to tour with them and other bands were interested in touring with us. And a lot more bands were interested in coming into my studio to record with me and getting Jake to design their records. On a personal level, doing something that resonated with people greatly affected my life outside of Converge in addition to inside Converge. Looking back on it, it was a major turning point in my professional life.

Newton: Definitely more people started coming to shows. It was definitely a gradual process, but it was happening. We suddenly got more attention from the metal community, too, and I think that had to do with the Terrorizer review. All of a sudden we were validated. People who had wanted nothing to do with us before all of a sudden thought we were great and wanted to go on tour with us. And because Terrorizer is based in the U.K., we noticed a vast difference when we went back to Europe. But honestly, I think Petitioning and When Forever Comes Crashing are more metal than Jane Doe—at least as far as blatantly playing metal riffs. The influence is certainly there on Jane Doe, but I feel like it’s a much more punk record.

Bannon: I try not to pay attention to outside opinion to our band, so I’m not really sure. My goal with the album was the same as any other—to create something that our band could collectively be moved by, challenged by and proud of. Jane Doe was that for all of us, so that’s the only real success that matters for me.

Jane Doe was your last album on Equal Vision. Were you already planning on moving to Epitaph at that point?

Ballou: No, we were planning on doing one more with EVR. They definitely ride a lot of fences between being a hardcore label and a rock label, and we couldn’t really get behind any of the stuff they had on the label. We did a few Equal Vision showcase kinda shows, and we just wanted to align ourselves with something that fit the spirit of Converge—not necessarily the sound of Converge, but what we were about. We still like the EVR guys and we get along, but we just felt like we didn’t have a lot in common with [their roster]. There were assorted tensions with them, but Epitaph approached us—we didn’t approach them. So we got this opportunity to work with a label that’s run by really good people who come from a DIY punk background and who still have those ideals. They run a successful business, but they still have that punk ethic that they had when they were younger—they still put art ahead of profit. Their basic philosophy is to work with established artists that are credible and have long-lasting success rather than seeking out the next big thing and jumping on it. I mean, they’ve made a few of those kinds of signings in recent history, but in general, I mean… they’re working with Nick Cave and Tom Waits—they’ve got a classic catalog.

Bannon: We were under the assumption that it was our last album for the label, but we didn’t pay much attention to that. Our goal was just to write and record the best album that we could at the time. The creative end of what we are takes precedent over any business nonsense. After the album was released and we did our first world touring in support of the album, we started discussing what we wanted to do next as a band. That is when we first started experiencing turbulence with Equal Vision. Our experience with Equal Vision was certainly not all negative. In hindsight, I feel that we simply grew apart from one another. Their direction and our own didn’t follow the same road of understanding. It was best that it ended when it did.

Newton: To be honest with you, a lot of it I don’t even know. I sort of treated it like, “Hey—whatever, man. I just play bass.” But I do remember thinking at that point that EVR was kind of getting away from hardcore. But it’s kinda weird, I guess. If we had stayed on EVR, I probably would’ve been fine with it. I mean, it’s a record label—who cares? But when the idea of signing to Epitaph came up, we were definitely really excited about it. They put out Tom Waits and Solomon Burke all this cool shit. Obviously, Epitaph has put out some duds that I don’t want to have anything to do with, but for every record they put out that I hate, they put out two that it’s obvious they put out because they think it’s good.

Do you think of Jane Doe any differently now than you did when you recorded it?

Newton: Yes and no—no in the sense that I don’t really dwell on stuff that we’ve already done. We did a record, we toured on it, and I’m onto the next shit. I’m proud of everything I’ve done, but I don’t sit around thinking, “Yeah—I wrote Jane Doe!” In that respect, it feels like it’s just something else we did. It’s history to me. But at the same time, I feel differently about it now that I’m able to step back and see how that record might’ve affected the hardcore scene in general.

Bannon: Not really. Each new album you write and release becomes the most relevant, so it’s not on my immediate radar—No Heroes is. But I am still excited by what the album accomplished creatively.

Koller: I like our new record No Heroes more than Jane Doe now. Maybe it’s because the songs are fresher and more energetic live, or I’m just older and my tastes have changed. I like how salty and heavy No Heroes is. It gets me pumped up and makes me want to punch concrete walls.

Dalbec: I still think it’s a great record, but after what happened I can not look at it the same way.

Ballou: Every time we do a record now, I always have to prepare myself for kids and reviewers to say it’s not as good as Jane Doe. Whenever any band does a landmark kinda thing, they’ll never get past it. Metallica’s never gonna do another Master of Puppets, you know? Slayer’s never gonna do another Reign in Blood—or Pantera and Vulgar Display of Power. So I don’t let that stuff affect me too much. Every once in a while I’ll read something or someone will say something to me that will make me feel like I’ve peaked, but when we were doing Jane Doe, we definitely weren’t of the mindset that we’d peaked. We weren’t chasing our own shadow. Which is pretty much how we work now, but it’s always in the back of your head. Not “Are we still good enough?” But “Are people gonna think we’re still good enough?” I don’t want my music to ever be driven by people’s opinion of it, but, you know, it’s hard to go about life completely independent of other people’s opinions of you. So it was nice to be in a situation, with Jane Doe, where I didn’t have to think about that at all.

In retrospect, is there anything you’d change about the album?

Bannon: No, nothing.

Koller: No, because the imperfections and rough edges are what gives the record so much character. A lot of my playing was really spur-of-the-moment and improvisational, and what I play live for those songs now is so much different than what’s on the record.

Newton: Oh, yeah. I’d rewrite a couple of the songs, for sure—like “Fault and Fracture,” definitely. It has parts that don’t need to be there and parts that are too long—same with “Heaven in Her Arms.” And I don’t like how the record sounds overall—it’s so compressed and metal. It sounds like it’s cutting into your ears. I guess that’s what some people love about it, but to me it sounds robotic. I like records with dynamics, where it goes from quiet to loud, where you can hear the guy breathing in the background when it gets quiet. But this record seems like it’s one volume—really loud and in your face—all the way across the board. At the time, I thought it was pretty cool, because there wasn’t another hardcore record that sounded like it. But in retrospect, I’m not very happy with how it sounds. And you can really hardly hear the bass on most of the songs—which is OK, I guess, ’cause I wasn’t happy with my bass tone. Overall, I think the songs on You Fail Me and No Heroes are much better, and I love the recordings on those records. Pound for pound, I think both of those records are better than Jane Doe.

It’s the time and place syndrome, though. People heard this record at a certain point in their lives and equate it with certain memories, so it holds a special place for them. For us, it’s the record where we really started to change as a band. We came out of our shells and said, “This is what we’re capable of.” With certain bands, it’s always one record that sticks with people. Like Entombed’s Wolverine Blues—that was the record where Entombed started to change, and it grabbed people’s attention. And there’s no other record like that record. So I can understand why people say that about Jane Doe, but it’s not my favorite record, personally.

Ballou: I wouldn’t make it so loud. [Laughs] No, I don’t know if I really would. But from an engineering perspective, I had to listen to Jane Doe while I was engineering and mixing No Heroes, because I had to make sure the new record sounded as least as good as that. And in the minds of some of the people in my band and some of our listeners, sounding as good also means that it needs to be as loud. Every stereo I’ve seen has a volume knob, but for some reason, people seem to demand that their records be obscenely loud. There’s not really much more space on a CD to make it louder than Jane Doe, so it’s getting challenging to make records that have as much or more impact from a sonic perspective. Other than that, I don’t particularly care for the chorus of “Fault and Fracture,” but there’s really nothing on the record that gives me idiot shivers. Prior to Jane Doe, there’s stuff in every song that we did that gave me idiot shivers.