Life is heavy for the guys in Eyehategod, make no mistake about it. And they, famously, take that crushing feel of heavy lives and turn it into crushing, heavy music, again and again and again. And they’ve done it once more with their excellent new record, A History of Nomadic Behavior.

To celebrate the release of the new album, which came out last Friday on Century Media, we caught up with vocalist Mike Williams to find out what five heavy albums changed his life.

Dead Boys – Young, Loud and Snotty (1977)

I still listen to this album more than most of the other stuff in my collection as it still holds true to that original 1976-77 sleazy punk sound I hold so dear to my heart. Forty-four years old now, this record is a blazing statement to real OG punk rock, crawling face down from the darkest corners of CBGB’s infamously seedy bathrooms. Dripping with sex, drugs and knife fights, singer Stiv Bators and crew prove this music is everything it says it is: tough, trashy and full of frenzied electricity. I always thought of this Cleveland band as the American version of the Sex Pistols, but without the politics and a way more down-to-earth street-level approach, but after years of listening I’ve gained more knowledge and changed my mind. The searing guitar action from Cheetah Chrome is manic here, and adding to that, the aforementioned Stiv’s menacing vox makes you fully believe in their filthy vibe. His catchy obnoxious phrasing is akin to contracting a venereal disease from a crummy downtown motel after running from the cops all night. Pure rock ‘n’ roll, the way the lord taught us.

Germs – (GI) (1979)

Darby Crash was a tragic figure; at least that’s how most people see him now, years later. He was the singer for the band the Germs, Los Angeles’ own chaotic masters. On stage, he was usually a wild drunken mess, most likely on quaaludes or some other tasty now-discontinued sedative. He rarely sang directly into the mic and tossed himself around the stage, starting fights and getting beat up. He dabbled in self-proclaimed mind-control techniques and felt he was a one-man dictatorship of some sort. Crash had his followers do damage and incite riots at gigs, leading to being banned from most of the venues at the time in the L.A. area. In the studio for this record, however, he pulled it all together and delivered a brilliant performance, snarling his uber bright and intelligent lyrics over the tight-knit pummeling music created by Pat Smear, Lorna Doom and Don Bolles. This album plays in my head on repeat. Savage and primal, yet rhythmic and demented. Darby’s life ended too soon when he committed suicide by overdose a little over a year after this album’s release, but he left us with this barbaric testament to hardcore punk in its early stages. It is truly ferocious, and brought me to where I am today. Side note: Avoid the Germs biopic at all costs… Hollywood ruins reality.

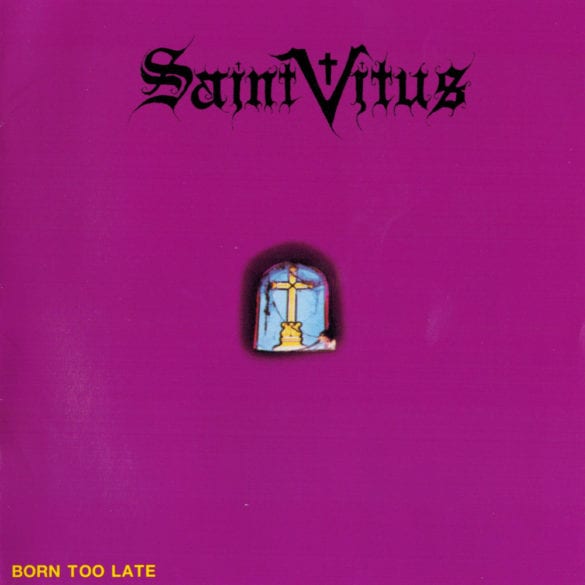

Saint Vitus – Born Too Late (1986)

Listening to and reading about Black Flag, and even asking Dez Cadena and Henry on the Damaged tour in 1982 about the band Saint Vitus, led me to that group’s first album on the SST label a couple of years later, and also to being a lifelong fan. That first self-titled record is amazing and I got to see them soon after I bought it as they were touring with a band called The Brood and played a small club with maybe 15-20 people in attendance. That was with original singer Scott Reagers, whom I adore as a vocalist and a person. However, the reason I picked Born Too Late as one of these five heavy albums is because it is the first Vitus full length to feature the legendary lifer Wino, a.k.a. Scott Weinrich. Wino had left his main band The Obsessed for the west coast and the open vocal spot that appeared after Reagers’ departure. I always loved Black Flag’s slower songs, such as “Life of Pain” and “Damaged I” because of the purposeful power of the ever-lovin’ dragging riff, but then Saint Vitus took that a major step further. Infusing Vol. 4 Sabbath with a thick, punker guitar sound warped with maniacal wah-wah courtesy of Dave Chandler that combined with Wino’s mournful, melancholy voice proved to be the exact force of nature that I needed. Another album I listen to on the regular.

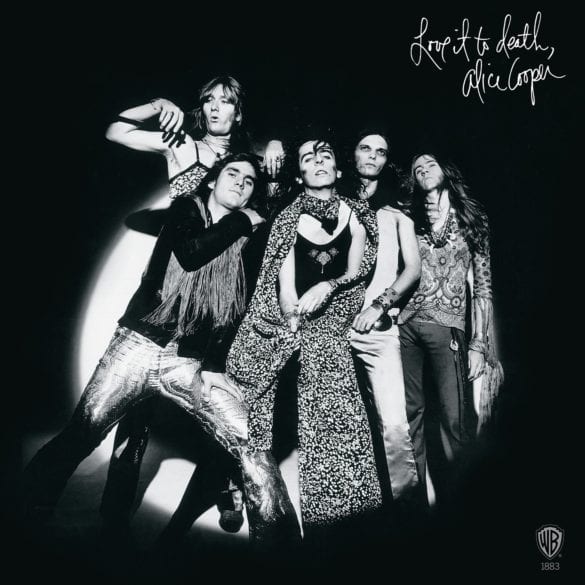

Alice Cooper – Love It to Death (1971)

Ahhh, Alice Cooper, swaggering pioneer of shock rock, heavily influenced by Salvador Dali and surrealist art, trailblazer from guitar-rock garageland and celebrity golfer meets boa constrictor enthusiast… What more can you say about the guy? Back in the day, Alice wasn’t just a guy, Alice Cooper was a group. A group that was a sum of all its parts, a mechanized product that functioned with an ultimate clarity and an unbridled will to break stereotypes and boundaries. I first heard Love It to Death as a small child of around 7-8 years old from my older brother and I was hooked from then on. Was it frightening to a kid that young? Yes, definitely, but that’s what drew me in. I didn’t totally understand such classic intense songs as “The Ballad of Dwight Fry” or “Black Juju,” but the mentally deranged ramblings of the mascaraed man hanging by a noose on the wall of the room I shared with my big brother spoke to me in a way that only one other musical outfit, that being Black Sabbath, did at the time. I think I understood the teenage anthem, “I’m Eighteen,” but it didn’t matter if I knew what it was about or not, the complete sonic mind-fuck of energetic battering drums and potent two-guitar gospel cemented the Alice Cooper group into my soul forever and ever.

Devo – Q: Are We Not Men? A: We are Devo! (1978)

1978—what a year. Space Invaders, Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple, the Star Wars Holiday Special and Devo. Seeing Devo on Saturday Night Live was a catalyst for me and a mighty big handful of like-minded outcasts to put aside our KISS records (only temporarily!) to delve deeply into whatever it was these two sets of brothers and one incredible drummer from O-hi-O were doing with music. The same year their debut album came out and thoroughly changed what I perceived as “music.” This record had elements of punk in concept and ideals, but was something far different, modernizing the usual themes and introducing the Theory of De-evolution to the world. Somewhat nerdy and surreal, the music itself was spirited, driving and based in authentic rock, though they were experimenting in strange new sounds. The use of synthesizers and avant-garde themes was confusing to some, while thrilling to others. I was one of the “others,” but that’s not to say I wasn’t baffled. That feeling of something seemingly from another planet brought me into their world and made it all the more sensational.

Q: Are We Not Men? opened the door to an entire universe of new sounds and I’ll never grow tired of it.