On August 10 of this year, renowned visual artist Dan Seagrave, painter of classic album covers from Morbid Angel, Entombed, Suffocation and countless others, went public via a Facebook post with his claims that Earache Records were selling “unauthorized merchandise… of his copyrighted artwork.” The post included a picture of two t-shirts, a longsleeve and a flag featuring the famous Seagrave album covers for Entombed’s Clandestine and Left Hand Path and Morbid Angel’s Altars of Madness. In his post, Seagrave alleges that Earache have no license “to use these specific artworks” for merchandise, stressing that he was “calling out Earache Records” and not the bands.

The following day, again on his Facebook, Seagrave posted screenshots of a cease-and-desist letter written by his lawyer Scott Sholder and himself, sent on July 20 of this year to “the company owner” of Rock Saws regarding the use of the three above mentioned artworks being rendered as jigsaw puzzles. The three-page letter describes in detail Seagrave’s claims of copyright infringement by Earache.

Despite Seagrave’s letter explicitly requesting that the jigsaw company do more than pass the issue along to Earache Records, Zee Productions, the company that owns Rock Saws, responded to Seagrave’s cease-and-desist letter to say that they “referred [the letter] to Earache.” In his reply, Seagrave says he asked Zee Productions how they could brush off such an accusation without at least asking Digby Pearson, owner and founder of Earache Records, for “proof by way of original documents that back up [Earache’s] claims to these three artworks in question.” Seagrave says he’s received no further responses from Zee Productions.

“I want to point out that my artworks appearing on Earache Records as ‘Album Covers’ is not what’s in dispute here and never has been,” Seagrave stresses. What’s at dispute, he says, is those artworks continuously being used for anything besides album covers. “The definition of album cover being: Vinyl LP, tape, CD and advertising relating to the record,” Seagrave elaborates. “This is not about the actual album cover use. It’s as [the album covers] relate to merchandise. My point is that the label does not own the copyrights, and so alternative uses beyond the record cover itself are not included for these Entombed or Morbid Angel artworks. Earache wants to bypass that by asserting a claim to my copyrights and now have expanded into further uses such as to make licenses with the Rock Saws company with my art.”

The jigsaws, Seagrave says, are only the latest infringement in a long history of such activity by Earache. In fact, the puzzles were noticed by our own editor-in-chief Albert Mudrian, who emailed Dan Seagrave to see if the artist knew anything about them. Seagrave says, at the time he did not.

According to Seagrave this dispute with Earache Records began over 20 years ago. “I haven’t kept an eye on it the whole time, but there have been ongoing uses of my art, most predominantly as Morbid Angel products, by Earache, which have been around since 2000 certainly,” he says.

“I became aware at the dawn of the ecommerce era, after chasing the label up for an outstanding payment for my art used on [Morbid Angel’s] Gateways to Annihilation record cover,” Seagrave says. “During this time [2000–2001] that artwork had been licensed out to third-party companies, including a U.K. poster company where a former Earache employee worked, an Italian textile flag company, and multiple apparel appearing on third-party website stores.”

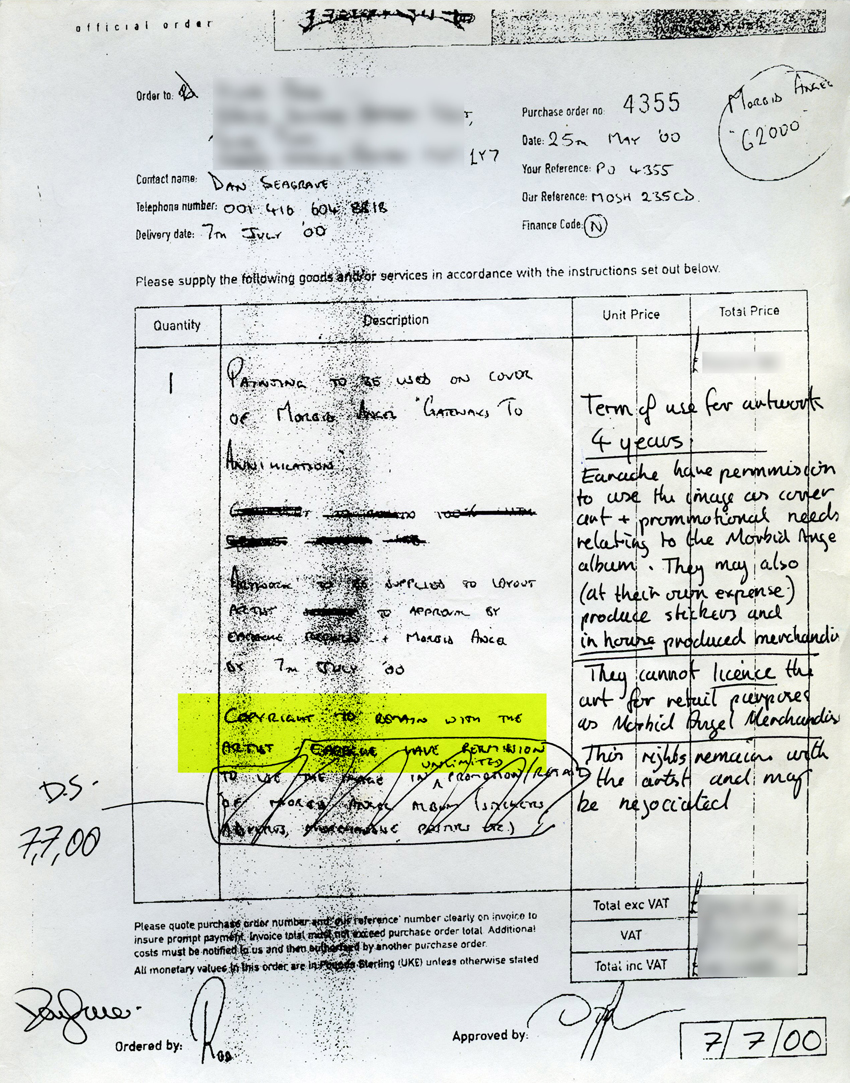

Seagrave continues, “When I was approached to work on [Gateways to Annihilation] after eight years since my last encounter with the label, my instructions to Earache at the start of this commission were that the fee would be for album cover-use only. No merch, and I retain copyright, to which the label employee agreed. Someone later wrote on their purchase order ‘merch use,’ so I struck that language and initialed/dated it by hand, in keeping with my aforementioned terms which were already agreed to. However, in my amendments, I did allow them an extra bonus use, a four-year term for Earache to make in-house produced merch. And specifically, not to be licensed out for retail.” He says, “These terms were sent back to [Earache] on their own letterhead and were not disputed at the time, and indeed, Earache published the art as an album cover and eventually paid for the commission.”

Yet, Seagrave says, “Earache continue to make in-house merch despite the license running out 16 years ago.” He further alleges that Earache have “denied licensing [his artworks] out even though plenty of third parties have made merch available for many years.”

The visual artist highlights several inaccuracies in Earache’s U.S. copyright registrations for some of the albums in question. Seagrave says, “If you look at Earache’s purchase order for Gateways to Annihilation, which by their own hand asserts me as the copyright holder, and compare that with their recent copyright registration, which asserts ‘work-for-hire’ as the terms of creation, that is an obvious contradiction. Upon further scrutiny the registration also displays a lot of incorrect data. Wrong date of art creation as 1999, and wrong publication. Offering [January 1, 2000] as the release date. Which is also months before I was even contacted about the album.”

Seagrave claims there’s more. “This is not the only registration with wrong dates,” he points out. “Left Hand Path and Altars of Madness also contain wrong release and creation dates as well as the incorrect work-for-hire claim. All these registrations were made by Earache from late 2016 – 2018 during the time my lawyer had taken over communications with them, and are available online to view in the Copyright Office directory.”

Decibel contacted multiple Earache employees, including Pearson, while assembling this story. When asked about this inconsistency, a label representative stated that Earache had “no comment.”

“As for my artworks for Entombed, my invoice document for Clandestine, [from] 1991, is signed by Digby Pearson to my terms,” Seagrave says. “The signature is evidence of the label agreeing to the terms on my form, and importantly only allows for LP use and nothing else. So, there is no provision for merch use at all and that remains the case to this day. There is also no transfer of copyright to this artwork. So, any merch appearing now in their store as well as [any] licensing [of] the art out as part of their own intellectual property is considered unofficial and an infringement.”

But—pay attention now—according to Scott Sholder, Seagrave’s lawyer: “Copyright registrations don’t vest ownership.” Sholder elaborates that a copyright registration “allows you to enforce your rights by suing in federal court and opens the door for the registrant to pursue certain statutory remedies.” But having a copyright registration for an album cover is not the same as owning an artwork’s actual copyright. Nothing short of an original contract signed by the author (artist) that plainly states a transfer of rights can substitute actual copyright.

As for why third-party companies like Rock Saws acknowledge Earache’s copyright registrations instead of Seagrave’s cease-and-desist letters, Sholder explains that, “The difference between ownership and registration is a bit counterintuitive and is likely not generally known, so it could be a mistaken assumption about what significance the registration has and what power it gives the registrant. I don’t know what’s in the collective mind of Earache, so I don’t know if this is the case here, but I can say that they have tried to leverage their ‘registrations’ when faced with our takedown notices to third parties who have then gone back to Earache, and some of those third-party sellers have deferred to those ‘registrations’ in justifying continued infringement.”

We asked our own third-party, one Daniel Katz, Esquire—also a certified metalhead—for his professional opinion on the situation. For six years Daniel Katz has been the solo practitioner of an eponymous law firm based in Philadelphia. Among other things, copyright law is one of his main practices. The way Katz sees it, Earache are acting “cavalier with the rights of others.” Katz says he’s “had clients deal with similar situations.” He says, “Most times, labels like this rely on the fact that they have deeper pockets and more resources than the artists who would want to sue them. It’s complete trash. It’s kind of like a divorce where two parties are vastly unequal in finances. It comes to a point where the more wealthy party can drag things out and make things financially impossible for the other party.”

We reached out to Zee Productions ourselves to inquire about the company’s policy when such allegations arise. Steve Beatty, Director of the company, responded: “Zee Productions has a valid and subsisting contract with the rightful copyright holder.” They directed us to the following video posted on Instagram, presumably, as means of proof.

A few days after Seagrave’s initial Facebook post, Earache’s U.S. label manager Al Dawson took to Earache’s Instagram to “tell [the label’s] side of this artwork copyright thing,” according to the caption for the post. In the video, Dawson, who refers to Dan Seagrave as “the guy,” begins by saying that since starting his job at Earache in 1990 “it’s always been the rule if you hire someone to create some artwork… they sign a form where they sign over their copyright, they get a full and final payment for the job and that’s that.” Dawson goes on to make a analogy about purchasing a “clunker” that he later tunes up before unironically extolling the wisdom that “just because you post something on social media doesn’t mean it’s true.” He then reiterates this idea that Seagrave’s artworks were under a work-for-hire agreement.

By time Dawson started working for the label in 1990, Seagrave and Earache already had two dealings for Altars of Madness and Left Hand Path.

Back then, “verbal agreements were all the label offered,” Seagrave claims. According to Seagrave, “The artwork appearing on the Left Hand Path record was made in early 1990.” He agrees that it was “a commission [he] undertook as a freelance home-based artist.” He says, “But there was only a verbal agreement for the use of this work on the record. Which was for album cover use, no merch and no transfer of rights or ownership took place to Earache Records.”

Earache began, Digby Pearson himself said, as “almost an anti-business plan.” Indeed, Seagrave recalls, “When I first walked in the door of the label in 1989, they were just starting out. It was two people, one office and a couple of records released. They did not have or offer contracts for artwork then, but also not 11 years later either.”

A thing about work-for-hire. As Daniel Katz explains, work-for-hire arrangements “are generally executed by employees or contractors of a company when they are in a position of creating intellectual property.” He continues, “You see this in tech companies as well as artistic endeavors. This is a situation that more often than not is covered by an agreement. Any time I’ve drafted one or reviewed one, it will explicitly use the term ‘work-for-hire.’”

Intellectual property “licenses are very specific,” Katz says. “For example, I’ve written one saying ‘this art may only be used on your album cover and if you want to make shirts, I need to approve it so it keeps the right of integrity (read: the work doesn’t look like shit) and I’ll need more of a fee.’ A mistake made a lot is not narrowly tailoring licenses as that allows ambiguity, which is never a good thing when it comes to rights.”

“The only paperwork that existed was my invoices to them, which could count as the only written agreements for all artwork up to the 1992 period,” Seagrave says. “None of those invoices included any transfer of copyright ownership. This again contradicts their recent claims that my artworks were created under work-for-hire conditions. But to which if it were true, there would be documents to show, and these would have been provided long ago for example to my lawyer in 2017. Besides which, the artwork used on Altars of Madness, occurred as a result of my first visit to the label, and the band picked it from an existing catalogue that day, and the label licensed it for album cover use-only per a verbal agreement. This art was a personal project, and in no way a commission.”

Few legacies in the history of extreme metal stand as conflict-scarred as that of Earache Records. Once a pioneering underground tastemaker, today a number of the musicians from those bands that Earache natured from their local death and grind scenes and into the international spotlight have harsh words and criticism for the label—several others have found themselves in legal battles.

Bolt Thrower called them “Arseache Records” after they reissued Realm of Chaos with a different album cover, allegedly affording no royalties whatsoever to the band. Yet former BT frontman Karl Willets replied specifically to say he had “no comment to make about Earache.” We reached out to numerous bands that have had issues with Earache in the past. All declined to speak to Decibel on the record. And given multiple opportunities, Earache themselves refused to respond.

But while we were waiting to hear back from Earache, another story surfaced concerning the label’s business practices. First Earache tweeted calling for Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of U.K., to “support musicians & all creative artists” throughout the Coronavirus pandemic. Soon after Johnny McBee, vocalist of American metalcore band the Browning, who released a pair of albums on Earache, retweeted the appeal to ask how Earache could be “so… concerned about the well being of musicians” when the label themselves, according to McBee, are “adding to the problem of instability and greed within the industry.”

The tweet, McBee says, was regarding Earache’s “doing some really sketchy things,” such as removing their first two albums from the internet “completely” and avoiding paying royalties to the band, among other accusations described in McBee’s response.

“I have held my tongue about this for so long now,” McBee tells Decibel. “Seeing them grandstand online about musicians needing help through these tough times, all while absolutely screwing over so many musicians. [The tweet] was the final straw and I couldn’t stop myself from calling it out. They’ve since deleted the tweet I called out, even more so showing their character.”

Moving forward, it’s clear that the burden of supporting responsibly is in the hands of the fans. It is up to us to buy thoughtfully, to make sure an appreciable portion of the proceeds are going to the artists behind the music and the visual arts we worship.

For their part, up-and-coming bands also need to be wary. “If you are a band, an artist, or anyone with intellectual property, the first rule of thumb is that you absolutely, before transferring or licensing rights, need to speak to an attorney,” warns Danny Katz. “The problem there is that most attorneys are expensive and completely out of touch with niche music. If you ask the average attorney what his favorite Earache album is, he’d look at you like you have three heads, so this alienates artists a lot of the time. I think a lot of people get swayed by album advances or other financial offers and just want to get their work out in some form, so they rush through things. I see this time and time again. I’d say 50 percent of my entertainment contract work is spent trying to get people out of contracts they’ve already signed to try to buy their rights back. It doesn’t work a lot of the time, because either the label/whoever is asking for more money than the artist can afford, or because they’re simply unwilling to stop exploiting whatever intellectual property they have acquired.”

Ultimately, fans still hold the most power. You’re free to support unauthorized jigsaw puzzles, or to contribute directly to LG Petrov’s GoFundMe. And you can support Dan Seagrave by purchasing high-quality prints of his classic album covers directly from his website.