The volume of tributes in recent days for fallen Power Trip frontman Riley Gale have been nearly as unprecedented as the emotions many of them have conveyed. Decibel will have one of our own in our November issue, but until then, we’d like to share the cover story of our long sold-out February 2019 issue. –ed

Future Shock

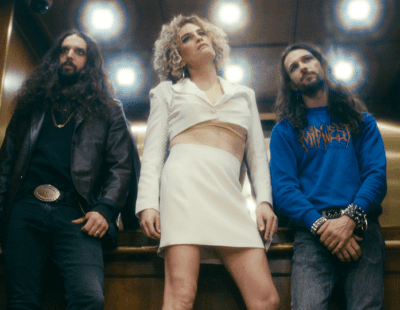

Ten years into its boundary-obliterating, expectation smashing run, Power Trip’s voltage is higher—and deadlier—than ever

You might assume Ryan Williams got the nickname “Hood” as a wild-ass white boy coming up on the wrong side of the tracks. Many do. But Williams isn’t from the apostrophe-lowercase-“h” hood. He’s from Arlington, TX. Suburbia, USA. In fact, the etymology of the sobriquet stretches back nearly 20 years to a high school classroom ruled by a teacher who had no love in her heart for the class clown with a laissez-faire attitude toward homework and attendance. Some days, she’d pull his desk right up until it faced hers, makeshift panopticon style. Others, she’d outsource her retribution by popping out to the sports field to snitch about the infraction du jour. “Yo, hit the neighborhood,” Coach would shout—Williams’ cue to run the mile loop of the adjacent housing block and an attempt at restorative justice that never quite took. Soon, to save time, Coach shortened it to “Neighborhood.” Then “Hood.”

“Got to be basically wherever I showed up at school—even in those rare cases where I hadn’t fucked up—everybody would shout, ‘Hood!” Williams tells Decibel. “Truth is, I ran a whole lot of fuckin’ miles.”

That innate rebelliousness naturally led Williams to the Dallas hardcore scene. “I was a lost kid, man,” he says. “Kicked out of every house I’d ever lived in. I mean, I’m not one that’s gonna dog my parents or point fingers or anything. I didn’t pave myself the best road either. I kind of fucked off school and everything else really hard. That’s just honest. But it’s also true that I needed somewhere to go every night, and the hardcore community became my home. Sometimes the hardcore community probably felt like my babysitter, so I’m sorry for that. [Laughs] Basically, I was cleaning up beer cans for a little money to get into shows and hang out with my friends. And Riley Gale was one of ’em. The best of ’em.”

Around age 18, Williams tried heroin and quickly spiraled into intravenous addiction. “The fuckin’ worst of the worst,” he says, his jovial, piss-taking patois briefly going hard. “I was the scum of the scum. I had given up on pretty much everything. Almost went to prison.” Mercifully, he landed in Narcotics Anonymous instead.

When Williams came out the other side, tiptoeing around the edge of a precarious sobriety, there again stood Gale, offering unconditional love and support, a place to stay and, not long after, a spot in the tour van of the new band he’d co-founded, Power Trip.

“I said, ‘Dude, come on the road with us—we’ll take care of you,’” Gale recalls. “‘We’ll figure this shit out.’”

What comes next is a beautiful metamorphosis: Williams’ history of raising hell and churning out miles on repeat proved invaluable in this new context. His position morphed from something nebulous to an artistic director/merch slinger/social media manager role in which he cleverly established the Power Trip aesthetic as something approximating Dan Seagrave chilling with Mike Muir at a circa-’86 CBGB show.

“I got seven years sober now,” Williams says. “At first, it kind of felt like a ball and chain was cut off my leg. I didn’t have to worry about how far I was from the dope house, you know? But if I didn’t have a friend like Riley? If Power Trip didn’t take me in? If I just went home and sat on my ass or took some bullshit job? Who knows what the fuck would’ve happened. While I was out with these guys on tour, a lot of my old friends were getting caught, going to prison. A lot of ’em were ending up dead. Sometimes tagging along felt like cheating—not good enough of a musician to be in a band, no money to travel. But Power Trip gave me something positive to focus on, something productive to do. Things gradually got better and better.”

At the merch table every night, Hood hears stories like his—tales of woe, of inspiration, of the outcast saved by a community and subculture that, to the outside world, looks like nothing but chaos and rage and violence and bleeding eardrums. He hears from the lost kids who aren’t lucky enough to be close personal friends with Riley Gale or have a reserved seat in the van parked out back, but nevertheless possess the next best thing: a Power Trip record. The words and music. The experience of a killer, life-affirming gig drawing strangers from near and far who may very well understand them better than their own kin.

It’s amazing that Power Trip is on Prince Harry’s iPod. That Ice-T calls Gale “Lil Jumpy Mane.” That the band hits the road with Danzig and might very well be the biggest Texas metal export since Pantera. No one would deny it.

At its core, however, Power Trip are, as Williams knows, an entity that enriches and saves lives. Did it save his?

“I don’t know, really,” he answers. “Can’t know. But I lean real fuckin’ heavy towards yes.”

MANIFESTATIONS

For Gale, the saga begins at his childhood home, hanging out as his mom listens to the radio while she cleans on Saturdays. He lets the warm waves of Motown and soul envelop his young mind. The first CD he buys with his allowance is the self-titled 311 record, the crunch-harmonics-crunch of “Down” priming his mind for the likes of Strung Out, NOFX and Pennywise, which a “motor sports bro” cousin from SoCal has him jamming for a minute. And then there were the Tony Hawk video game soundtracks and turn-of-the-century expeditions into Napster and MP3.com. “I wasn’t really aware of the distinctions other people made between the different kinds of music I was discovering—and I’m glad I didn’t,” Gale says. “All this stuff was just cool and new to me.”

Extreme music hit last, but hard. In his late teens, Gale would ride shotgun in his friend’s big red Dodge Ram, soon dubbed the “Slayermobile,” Reign in Blood blaring on a loop. From there, the trail took on more sinister hues and tones—Napalm Death, Obituary, Sepultura, black metal. Gale “drifted more towards the dark and the political side of metal,” and never looked back.

Through all these years, Gale was a “listener, not a participator.” The saxophone that tempted back in fourth or fifth grade was too expensive. In middle school band, the powers that be wanted to limit him to a single lonely snare. If there’s one thing DIY hardcore does well, however, it is creating participants. You don’t need to be able to shred like Yngwie to plug in your guitar, or croon like Michael Bublé to step up to a mic and sing the pain or rage in your heart. So, Gale resolved to front a hardcore band—and do it his way.

“I really only have two metal influences as far as vocalists go,” he says. “One of them is John Tardy and the other is Paul Baloff. That’s it. The rest are guys like fucking Freddie Mercury, James Brown, Al Green—shit like that.”

Meanwhile, in Fort Worth, a wunderkind guitarist named Blake Ibanez, who’d been shredding in local hardcore bands since age 12—“My parents were always pretty cool about me doing music stuff,” he says, “probably ’cause I didn’t get into trouble and got good grades”—had at 16 begun to rethink the direction of his then-current outfit. The group also counted guitarist Nick Stewart—a choir singer who found aural succor mostly in the alterna-rock recommendations of his grunge-loving father until free tickets to a Hatebreed/Sick of It All/Terror show at 15 flipped the script—and bassist Chris Whetzel—whose family remained ultra-supportive even when he took a hard turn from strumming guitar at the church toward summoning the diabolus in musica around 13—amongst its ranks.

An encounter with a couple of 1989 metal-meets-hardcore masterpieces—Leeway’s immortal Born to Expire and Cro-Mags’ left turn Best Wishes—sent the trio down a crossover rabbit hole: Cause for Alarm, Agnostic Front, Sacrilege, Nuclear Assault, Vio-lence, Killing Time and others, alongside local Texas influences Bitter End and Iron Age. What was on Ibanez’s mind, however, wasn’t imitation, but rather refracting crossover through an entirely new prism. “I get a lot of inspiration from stuff that has a real pop sensibility,” he explains. “I like hooks, melodies, songwriting tricks.”

Stewart, for one, wasn’t surprised by the quantum leap in the practice room. “Blake was really young when I met him,” he says. “I think he was 15 and I was about to turn 18. The thing I noticed right away is how inquisitive and engaged he was—he had this eclectic, cool way of looking at the world. And once I started playing in bands with him, I saw how that translated into the music he writes. I mean, he’s a machine—a fucking genius, really. Bands nowadays seem to think they need to change up time signatures or be super technical to stand out, but Blake took it in the opposite direction. He’s super into ’60s pop music and stripped-down, classic song-structuring. Tapping into that sort of beautiful simplicity and power has helped our band so much.”

Serendipity has always been a part of the larger Power Trip story. In ninth grade, for example, Whetzel had a strange and fateful encounter: “A guy stopped me out in front of my high school—usually an intimidating place to walk by anyway—asked about my AFI shirt, then handed me a burned CD with a bunch of Bad Brains songs on it,” he says. “Still see that guy from time to time. Don’t know where I’d be if it wasn’t for that.”

Perhaps, then, we should not be surprised kismet came calling again. While undergoing his own crossover conversion, Gale’s band was breaking up. Already scene acquaintances, the 16-year-old Ibanez reached out to the 22-year-old free agent vocalist.

“I think the only reason I even went to meet up and jam was because his parents lived in the same town as my parents,” Gale says. “So, when I came home from college one weekend, I was like, ‘Yeah, sure, I’ll come over and see what you’ve got.’ If he lived somewhere I had to drive more than 20, 30 minutes, the band may have never even started. His band before was good, but I didn’t know if we were gonna be able to do what I wanted to do. He and I immediately hit it off, though—wrote the whole demo in basically one sitting.”

So, musical compatibility erased the significance of the age difference?

“Well, let’s not fucking kid ourselves: Blake and I probably couldn’t be any more different personality-wise,” Gale admits. “It may not be a full-on Gallagher brothers feud, but we’ve definitely got that classic sort of Lennon/McCartney kind of thing going on. We’ve learned over the years to kind of acknowledge that, accept our differences and move forward. It has not always been easy. But our friction—fighting over vocal patterns or riffs or transitions or whatever—oftentimes has resulted in some of our best music. So, in that respect it’s… great. It feels familial.”

“You’ve got to understand—at the time, Riley’s band was the king of Dallas hardcore,” Stewart remembers. “He’d promoted shows that helped build the scene. I remember when his old band went on tour, I was like, ‘I can’t believe he’s just going to get in a van and go.’ That was wild to me. I’d only been out of Texas, like, twice before Power Trip started—I had no idea what was coming! Riley was older than us, had done a lot of cool things, made a positive impact. We were already like, ‘This guy’s awesome.’ But what he brought to the table was so much crazier and greater than I expected. His vocal approach was so raw, so real—people can’t not pay attention. And then once he has that attention, Riley’s got this ability to be so thought-provoking and energizing in just a few words. Anyone who ignores Riley’s lyrics is missing a huge part of what makes this band special.”

The new band recorded a demo in the bedroom of Ibanez’s best friend at the time, Mark Rubin, who also played drums. “He had to leave the band within a few months,” Ibanez explains, “because his parents wouldn’t let him play a show out of town.” (Rubin was 15.)

A year later, 2009’s buzz-creating Armageddon Blues 7-inch dropped via Double or Nothing Records, catching the attention of Triple-B Records founder Sam Yarmuth then pulling together the America’s Hardcore comp, which would eventually encompass a murderers’ row of rising hardcore bands, including Backtrack, Rotting Out, Cruel Hand and Title Fight.

“I got the ‘[The] Hammer of Doubt’ master, and my mind was instantly blown—unbelievably fast, unbelievably thrashy and hard,” Yarmuth enthuses. “Right from the get-go, I knew this was going to be the biggest song on the comp. After it was released, I remember everyone texting me being like, ‘What the fuck is this Power Trip song? It’s insane!’ I think that track helped the band get on a lot of people’s radars. I knew that they were destined for big things.”

CROSSBREAKER

“By the time we finished that record, it felt like we’d been through a war. But a war we’d won.”

So says heavy music producer extraordinaire, musician and close Power Trip confidant Arthur Rizk (Cavalera Conspiracy, Code Orange, Crypt Sermon, Mizery) about the process that produced 2013’s breakout full-length debut, Manifest Decimation.

“I’d been playing with this band Iron Age and staying at the singer’s house, who lived in Austin,” Rizk says. “I met Riley and we became friends. Maybe a year later, Power Trip was on the Triple-B comp. I got a copy because I’d recorded the Title Fight song. I thought, ‘Oh, Riley’s band,’ but wasn’t really prepared. ‘Hammer of Doubt’ just fucking killed me. It was crossover, but also had a uniquely heavy thrash aspect to it—that older Exodus, older Sepultura vibe. Yeah, every hardcore band loves Chaos A.D., but how many give it up for Arise? It was all fucking breakneck speed, solos, dive bombs, untouchable vocals, crazy smart lyrics. I was just getting into recording and producing at that point. I got in touch with Riley and said, ‘Dude, we gotta do something together.’ Like, I didn’t care what I needed to do to make it happen—it needed to happen.”

“I don’t even know if Blake was 21 yet, and that was the first LP he’d worked on,” Gale says. “That was my first LP to work on. There was a lot of pressure on us already just from sort of the small bubbling kind of hype we had in the underground. For anyone who really cares about putting out a good record—especially perfectionists like us—recording is hell. That’s just the reality of it. But I believed in Arthur, and he took Manifest to a level we couldn’t have imagined, really. I think that man is going to one day be as revered a producer as a Steve Albini or Ross Robinson. He’s going to be massive, and he’s completely integral to this band and what we’ve accomplished—on record and beyond.”

“The idea was to try to capture on a record the feeling of just watching a room explode and 50 kids jump off a stage in three minutes,” Rizk continues. “That was my obsession. Luckily, in 2018, you have an infinite palette as a producer. If you have a vision and some skill, you can just make it happen. So, if I’m suddenly like, ‘You know what? I wanna make this fucking snare sound like Metal Church’s first record,’ that can happen. My attitude was, ‘Let’s not worry about making everything sound clean because every other band is sounding clean right now.’ Our goals were to deconstruct that shit. Fuck perfection. I wanted feeling.”

He got it. So did the band, now firing on all cylinders with multi-instrumentalist/Mammoth Grinder bassist/vocalist Chris Ulsh slaying behind the kit. (“The man is amazing at anything that he does,” Gale gushes. “He doesn’t even have to try.”) Manifest Decimation captured hearts and minds while blasting open doors. A turning point: Power Trip blurring lines and melting faces as the opener of the 2016 Lamb of God/Anthrax/Deafheaven tour. The stage was set for the triumph of 2017 sophomore effort Nightmare Logic, which saw the quintet fully transmogrify into that rarest of birds—a scene-unifying band, beloved with equal fervor by metal and hardcore fans.

“The first thing that popped into my head when I heard their name was the second Ludichrist record, honestly, which was amazing to me,” says ex-Leeway guitarist Michael Gibbons, who pioneered and perfected the crossover sound on the aforementioned Born to Expire and 1991’s Desperate Measures. “But after listening to them, I found them to be an excellent group. Total brutality with a melodic aggression in their style. Proficient players all around. Glad they’re carrying the torch going forward in an honorable method… I was always way more a crossover style player than just either a straight NYHC or standard metal player, so I can totally connect with their artistry in how they compose their songs and writing structures.”

“Power Trip remind me of everything that I loved about thrash metal in the 1980s,” agrees Dwid Hellion, legendary frontman of Integrity and a visionary hardly given to insincere or voluminous praise. “I’m grateful that they are breathing new life into the genre.”

“There have been plenty of other bands that started way after us and rose up much faster,” Gale says. “I’m not envious at all. There’s a freedom in knowing you built your foundation organically—that you’ve earned everything you’ve got and it’s not just hype. You know, the hardcore scene gets a lot of shit, but in general, compared to other subcultures, hardcore kids are pretty enlightened. They have taste. I’m glad we came up in that scene first because we always felt if hardcore kids took us seriously, maybe we were doing something right. It wasn’t bullshit. That gave us the confidence to take our music in front of any crowd.”

“I liken it to a genuine connection between Power Trip and the fans in every single city,” says Brent Eyestone, the Magic Bullet Records/Dark Operative proprietor responsible for bringing a 2016 Power Trip/Integrity split as well as recent compilation Opening Fire: 2008-2014 into the world. “The guys legitimately enjoy doing what they do and unquestionably appreciate every single person that has ever supported the band. I am consistently blown away by how checked in they are with all of the other active bands and scenes happening around the world, regardless of genre. They lift up whatever and whoever is doing great things in their eyes—even outside of music—and there’s no sense of competition or selfishness. They are smart enough to understand that all successful, sustainable movements need a legitimate community in place, and that it can’t be faked. They embrace that, and they exemplify it flawlessly.

“Personally, I am certainly like every single Power Trip devotee/affiliate,” he continues. “This bands means something more—something unquantifiable—that drives me toward a level of allegiance that transcends traditional friendships and working relationships.”

SCREAMING OUT OF THE ABYSS

Eyestone is in an Uber from the airport to Canton Hall in Dallas. The driver is a person of color in his mid-50s. He asks why Eyestone is in town. A metal band he worked with was celebrating its tenth anniversary, the label honcho replied. “He asked what band and I spilled the beans,” Eyestone says. “His response was par for the Power Trip course: ‘I know that band! I’m a bartender when I’m not driving. Worked a few Power Trip shows in my day. Their crowd is good tippers. Good people. That’s going to be a good show, man.’”

It’s a story that encapsulates the Power Trip mystique and phenomenon as well as any other, a pearl the band strives to protect even as its popularity skyrockets.

“Look, I’ll admit these days it’s hard to be social,” Gale says. “It’s hard to walk out in a crowd of 800 people where everyone wants to talk to you. So, yeah, maybe I’m backstage all night. But when we’re onstage? I want people to feel connected. You aren’t just watching a show. You’re here with us and I wanna talk to you as a fellow human being. What I see in our crowd is [people] who understand how fucked up and cruel the world is, but despite it all, want to be good to each other and have an outlet to express their frustrations in a safe and cathartic way that doesn’t lead to real fights, or harming themselves, or bottling it up inside until it becomes poisonous. In that respect, they’re us and we’re them, and none of us have to fake shit with each other. If I ever want to be something I’m not, I’ll go into acting. That’s not what Power Trip is for.”

The sentiment is legit, says Eyestone, offering a story about a stage diver getting knocked out at the Canton Hall show as evidence, the band stopping on a dime when Gale signaled that something was awry. “They kept everything silent so that venue staff could attend to the situation effectively, all while handing out bottles of water to anyone that looked overheated in the pit,” Eyestone marvels. “Less than a day later, the band is chatting with the kid on Twitter, making sure everything continued to be okay.”

“When you get into a bigger league and you find yourself going to the festivals, eating the free catering and getting free guitars, you feel like you can put your feet up at that point,” Rizk says. “I’ve seen a lot of bands do that. And it’s just not the case with Power Trip. They stay fucking hungry. Even to this day, I’m getting texts from Blake with new riffs and new ideas. They could just be sitting back after their tour with Danzig and just, like, fucking drinking and hanging out, but they’re already back to work. It never stops.”

That’s just who the band is, Whetzel insists. “We never thought we’d be doing half the stuff we get to do, and are happy to be where we are,” he says. “[But] I come home from every tour and go back to work at a local music/pawn shop in town … It’s honestly a great feeling after 30 days on the road to be able to go to work and come back down to earth, you know?”

“We all have our own style and interests, musically or otherwise,” Ibanez says. “I think people just see us as cool dudes, relatively ‘normal’ or relatable, not dolled-up metal dorks/rock stars. We try to be cool to everyone we meet. We pretty much always make friends with the bands we encounter or tour with. We’ve come to know a ton of people in the underground music realm over the last 10 years. I think it just gets around that we’re real about what we do and who we are.”

TEXAS-SIZED TRIP

For a long time, Gale says, Texas was an island. “On one hand, it was hard to get bands to come through here,” he reminisces. “On the other, we’re not spoiled like a lot of places.” Believing the energy, fire and devotion of the Texas scene to be severely underrated, Gale chose to do more than show up to innumerable gigs and scream into mics. He also ran an under-the-radar DIY venue, booked shows elsewhere, and served as an ambassador to the outside world whenever possible. Texas, in turn, learned to love the ever-loving fuck out of Power Trip.

“We just got a reputation as this wild band from Texas,” Gale says. “When we played, people would go crazy. And we instigated stuff like that. I love that kind of shit. I grew up on it. I grew up seeing bands from Houston like Pride Kills and Your Mistake that would be considered tough-guy, but were actually inclusive dudes putting on these crazy shows that ended with fire extinguishers and riots.”

“Being from Texas means you’re proud of your home state and ashamed of it at the same time,” Decibel contributor and one of the great chroniclers of Lone Star State heaviness Andy O’Connor says. “There’s a lot I love about Texas. There’s also a lot I hate about it—a lot of really fucked up stuff. I mean, have you seen who’s in power here? Having a band like Power Trip crushing it really helps reconcile the great and the shit about Texas. You’re not a real one if you don’t carry some contradiction with you.”

Well, Texas, Power Trip love you back. As the shout-outs to any Texan in the audience at every show make clear.

“Texas has a really cool history that not a lot of people know about,” Gale says. “It’s a tight-knit scene. We’ve always made it a point to say thank you. Because those are the people that raised us up. Because it’s important they know we remember and appreciate it. I’m sure there are a ton of Texas people reading this article like, ‘Yeah, they’re talking about me. I’ve been throwing down for these guys since day one.’ They’re not wrong! Knowing that feeling of growing a scene from virtually nothing… I never thought Power Trip would achieve anything like this.”

For Gale, it’s about keeping the flame that illuminated his own youth alive; of keeping the faith so Power Trip might perhaps gift to some new crop of kids (Texan or otherwise) the same thing that, say, a Bane show in the early 2000s provided him: The chance to meet like-minded people from around the corner—or Austin, or San Antonio—to the beat of an enlivening soundtrack and, while celebrating individual contributions, become greater than the sum of the parts.

“Texas still supports the shit out of us, and that’s cool with me,” Whetzel says when asked about Gale’s words. “I’ll probably live in Texas forever. That might not answer your question, but that’s what I’ve got to say about Texas and this band.”

OF PLATFORMS AND RESPONSIBILITY

The increased reach and influence of Power Trip weighs on Gale’s mind as the band prepares to write and record their third full-length for a tentative late 2019/early 2020 release.

“I do want to be an activist,” the vocalist stresses. “I’m not one yet. Like, right now I might get up onstage and say, ‘Be good to each other’ and mean it, but that’s not the same thing. I’ve sort of found myself in a position where maybe people are paying attention and maybe my responsibilities are changing—even if I still don’t quite have my own shit together.”

He’s got this feeling he can’t shake—doesn’t want to shake—of needing to affect positive change: “I just want to make this world better in some small way. I just want to do… something.”

For Gale, this inner yearning is part and parcel of Power Trip. Formed in the long shadow of 9/11, the message of the band has always been tied to Gale’s belief that darker days are coming; that, in his words, “I’m going to see some really terrible things in this lifetime.” When the creeping apocalypse does arrive, what will serve us better? Love and unity? Or homophobia, xenophobia, racism, religious intolerance and all the rest?

“It’s weird,” he muses. “I honestly don’t know what I’m gonna do for our next record in terms of lyrics and theme. I’m not afraid of being clear with my political views. I’ve just preferred to this point to express myself with allegory and symbolism and metaphor—that way, people can enjoy it at face value, and if they want to dig deeper then, great, there’s something there. I may not have the eloquence of, say, Barney [Greenway] from Napalm Death—one of the best frontmen and lyricists in metal, period, as far as I’m concerned—but I think I would sometimes like to be more explicit. It’s a delicate process. Like, if I can’t find a way to write a song that promotes feminism or anti-racism or gay rights effectively, it’s not going to be a unifying thing. In fact, it might be the opposite. So, it means a lot to me to get this right. And I haven’t quite figured it out yet.”

His own apprehensions notwithstanding, Gale speaks with passion and, yes, eloquence on any number of social challenges and ills. He becomes quite animated discussing a run of shirts benefiting the first LGBT homeless center in all of Dallas and the plans to vastly expand such efforts moving forward.

“I’m proud of these guys for not being afraid to stand up for themselves and the various communities they identify with and are legitimate allies toward,” Eyestone says. “I think their convictions and altruism is precisely why their audience continues to multiply exponentially with rabid fervor and undying allegiance.”

The recent Adult Swim Singles track, “Hornet’s Nest,” could be a harbinger of activism to come—a people-powered call to arms against income inequality, which Gale summarizes thusly: “There’s always going to be so many more of us than there are of them, and all it takes is us waking up to kill them with a million stings.”

“I’m taking this one step at a time because it literally is a new step everywhere I put my foot,” Gale says. “This could stop at any moment. The world is fickle. If the band ends tomorrow, I’m fine. We’ve already accomplished everything that I ever wanted to accomplish and more. Until then, my attitude is, ‘Let’s take this as far as we possibly can.’”

“None of us really know how we got such a hot hand at dice,” Williams says, “but more than any of us, I’ll fuckin’ take it.”