Venues taking a cut of a band’s merch sales are a nightly reality for most touring metal acts. Decibel examines the practice’s effects on the U.S. touring market and if it’s sketchy business or a necessary evil

Picture this:

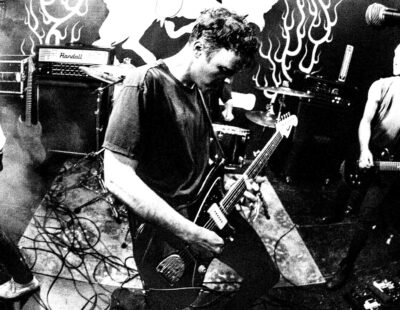

You’re in a touring band playing a string of cities. You’re dealing with shitty food, disrupted sleep and long drives, but are generally having a good time traveling highways and byways with your bandmates, meeting and making friends and fans along the way. However, your pockets feel a little light as downloading and streaming have erased a chunk of your band’s income, as has the burgeoning bootleg merchandise market. And let’s not forget about the manager and booking agent who get a cut for helping set up these shows in the first place.

Picture playing a slamming gig to an assembled gathering of appreciative proponents of your musical gospel. After the amps are turned off, those folks show love and support by opening their wallets and scooping up assorted items from your merch table, the sales of which play a big part in keeping the sails spread on the Good Ship Your Band. Then, picture this: Someone approaches you at night’s end, demanding anywhere between 10 percent and 40 percent of the evening’s sales totals. “Sounds like a bunch of Whiskey Tango Foxtrot bullshit,” some of you are likely exclaiming, but it happens. It’s called a merch cut, or merch rate, and it’s when a promoter or venue collects a percentage of a band’s merchandise sales. It’s an accepted industry standard that understandably riles touring bands as it places another set of fingers in an already thinning fiduciary pot.

“It’s annoying to no end,” Tomasz Wróblewski says. Wróblewski is better known as Orion, bassist in Polish blackened death metallers Behemoth and someone who’s thoroughly frustrated and disgusted with the practice. “It’s rarely ever been explained why it happens and where the money handed over ends up. It’s good that someone is finally talking about this, to make people aware of this situation.”

The Creature from Manhattan Island and the Sunset Strip

Unless it’s voluntarily being given away, or government is involved, it’s a good bet that anyone who’s ever had money in their pocket isn’t, without there being a compelling reason, going to hand over any portion of their wad just because someone else asks. On the surface, this is how the merch cut operates: A promoter or venue takes money they’re not expressly entitled to from a band that has sold its goods to the paying customers it brought into an establishment. Beneath the surface, those putting on shows, usually in venues with 400+ capacities, feel deserved of compensation for making the show a reality. Regardless of the opposing arguments, there seems to be no clear-cut starting point as to how and why merch cuts became a thing in the first place.

“From what I gather, in the ’80s, straightedge bands were getting bigger and looking to play bars,” muses Pat Sheridan. Sheridan has been on the scene for a minute. Straight out of high school, the guitarist joined NYHC band Terrorzone in the early ’90s before moving on to play in Shattered Realm. He now slings his axe in deathcore bruisers Fit for an Autopsy and regularly deals with merch cuts in his role as the band’s de facto tour manager. “But because those bands wouldn’t bring in a drinking crowd and revenue at the bar, the bars weren’t interested. So, the bands started giving them a cut of merch to offset the lack of drinkers. Smaller venues would do it, then promoters working these venues would carry it over to the bigger venues and it eventually became the norm that bands would be paying a percentage of merch for absolutely no reason.”

Jason Netherton, formerly of Dying Fetus and presently of Misery Index, has been touring and dealing with merch cuts since the late ’90s. In piecing together anecdotes and lore from various sources, he speculates that the practice goes back even further.

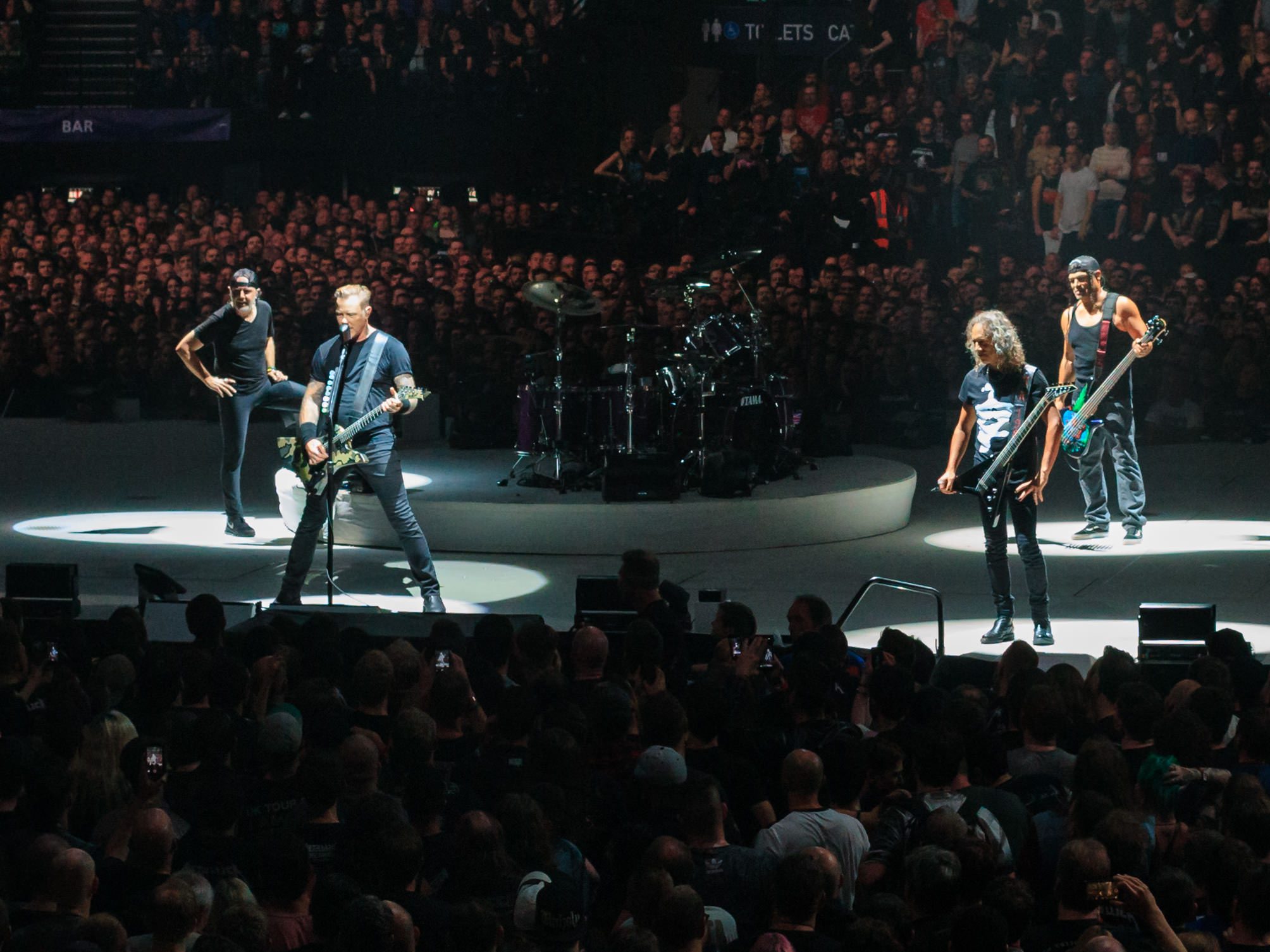

“At the arena level, it probably started as a means of compensating vendors for providing the manpower to sell large volumes of merch. However, at the club level, I believe this practice started in Los Angeles and New York City during the ’70s and ’80s, when the tour shirt emerged as a standard show souvenir item. This new revenue stream didn’t go unnoticed by the local entrepreneur-promoters and venues. Traditionally, promoters and venues make their money from the excess profit on ticket sales. However, during the late 20th century, when merch sales became standardized as a revenue stream, promoters and venues began to see thousands of dollars from the audience going directly to the bands, all within the context of the concerts that they booked, promoted and provided a space for. This is where I believe a critical change of perception occurred: Entrepreneurial promoters and venue owners started to see their role in doing the promotional work and providing the space for the concert as important in making the shows happen. Therefore, in their view, since the money from merch sales was taking place at a show they booked and on their property, they would claim a portion of those profits. Word got out and promoters in other cities started introducing the practice, which was then instilled into the contracts promoters and venues made with booking agents.”

“It’s been a thing for as long as I can remember,” says Inertia Entertainment’s Noel Peters, a promoter with over two decades of experience booking metal shows of all sizes in Toronto and southern Ontario. “I’m not sure about the history, but on a club level, a lot of it is apparently about offsetting the alcohol sales. A band sells a T-shirt for $20, for example, and theoretically the venue is losing out on the cost of a beer. So, implementing a 20 percent merch commission brings that $4 back into their pockets. I’ve also heard that it’s also about offsetting the cost of all-ages shows where minors are buying merchandise and not drinks. Some venues will use it as an extra revenue stream to make improvements, like a digital soundboard, which can cost six figures, or monitor boards, which can run $50,000. If you don’t have state-of-the-art gear you’ll lose events to other venues. At the same time, I’ve seen venues that are complete dumps take a merch cut and not do anything with the money.”

Behemoth’s Orion may not be sure about the history behind merch cuts, but he believes it’s as simple as the industry turning the idea of demanding money for nothing into formal practice via contracts and legalese.

“Music is a business and the venues, agents and event companies see where people are spending money. I think it’s as simple as, ‘Let’s fabricate reasons for us to have a cut of it, because we can.’ There’s no real reason behind it, but because they’re bigger, stronger, more influential than a single band, they can, and the bands can do nothing.”

These days Peters is a full-time promoter but he has a unique perspective and understanding as a former owner/operator of Toronto clubs.

“As a previous venue owner, I can look at the flipside of the coin. A venue generally isn’t raking in millions of dollars nightly at the bar. It’s a sum of all parts; you might have had a great night one night, but the next night could have been a bust, and merch cuts are an additional revenue stream.”

Ashley Felk has been “touring around for about a decade” as an onstage performer/backing vocalist with the Genitorturers and as a merch vendor on the Mayhem Festival tour and for the Obsessed, Corrosion of Conformity, the Faceless and others. However, when at home in Austin, TX, she works at a venue called Come and Take It Live, where part of her job is to collect merch cuts at night’s end.

“Our situation is a bit different because the promoter owns the venue. Earlier this year, before he bought it, there were shows put on by other promoters, which didn’t have merch cuts, but it’s a lot harder than people think to make money in this business, especially because it’s a bigger club with around an 800 capacity. The metal shows do the best here, but a bunch of different genres come through, from country to rap, and it varies; not every night is a good night. So, we have a 15 percent rate on soft goods—like T-shirts and hoodies—and that money goes toward my paycheck and the renovations that needed to be made. The entire sound system was replaced, they got new lights, put in a new sound booth and built a new green room, because before it was a venue, this place used to be a lumberjack-themed sports bar!”

Battles at Home and Abroad

“When it started for us was in the U.S. 10 or so years ago when we stepped into New York venues,” recalls Orion about initially being confronted with percentages being taken from the band’s merchandise. “When we started talking to other bands, we realized it was a common practice in the U.S. In the beginning, I would ask simple questions about it and they would tell me it was the law and it came down to taxes and having to pay taxes. I would say, ‘OK, show me the tax form. I will pay taxes on merchandise where we have to.’ But I rarely saw anything. As things have gone on, we see 40 percent quite frequently when it was 10 percent, 15 percent or 20 percent before. It seems like the bigger your band, the more they squeeze out of you. And more and more venues in Europe are doing exactly the same thing.”

Still, Sheridan views merch cuts as “an American music culture thing,” though he does acknowledge bands encountering it in other regions and countries and speaks of overseas bands touring America for the first time and going through the five stages of grief (denying that a merch cut exists, being angry that a merch cut exists, bargaining in an attempt to get out of paying it, being depressed about forking over money and accepting the way things are) when encountering the practice for the first time.

“I think it’s because the ‘Old World’ and the United States have fundamentally different views of the purpose and role of artists and art in culture and society,” reasons Netherton, expounding upon Sheridan’s belief. “In Europe, art and artists have traditionally been seen as more valuable for social and cultural efflorescence. There is a long history there rooted in Romantic and sublime notions of art, which is somehow antithetical to commerce. As such, the arts are publicly and graciously funded through grants, stipends or via the maintenance of cultural and youth centers. In the U.S., the arts and culture are more often left to be funded by market-driven imperatives. As such, artists and musicians are more likely to fend for themselves, receive less institutional support and encounter more market intermediaries seeking to make money off them. In Europe, I find that promoters view the artists and the bands as entirely the reason why the shows are happening in the first place and are OK with the idea of making all their money from having a successful show. In this case, bands and artists are perceived as the source of creativity and therefore what draws the audience to the venue in the first place, as opposed to American-styled, hyper-capitalistic practices and the perception of the band as somehow doing business on the property of the venue where merch sales should therefore be taxed.”

“It’s been happening in Europe for five to seven years,” confirms Orion, “and it’s becoming more and more popular. All the bigger venues in Poland have started doing it. The last European tour we did, I’d say about half of the venues took merch cuts. I’m talking about 2,000-capacity venues because I believe the bigger the venue and the more aware they are of what they can do and get away with, they’ll do it. It’s been awhile since we’ve played clubs, but I want to believe they have a different approach and understand that who is really making this business move are the bands. As I see it, it’s basically robbery because it’s not their money, they haven’t earned any of it at any point. It’s a symptom of growing capitalism.”

“Some venues are very corporate and strict,” says Felk. “Places like House of Blues or arena shows will have people count what you bring in and count out at the end of the night to make sure you’re not fucking with them and they’re getting their proper percentage. We try to be fair and at least keep our percentage consistent.”

Unsurprisingly, it’s a practice that leads to conflict because its perception as an egregious money grab is often at the crux of the matter. Bands are witnessing their piece of the pie become smaller, often arbitrarily and unjustified; a venue/promoter feels entitled to compensation for their promotional work and providing a location. The whole mess becomes a bone of contention that show-going fans often never even realize is happening behind the scenes.

“I had a tour manager come into a venue and be completely dissatisfied with the hospitality and amenities one time his band played there,” recalls Peters. “He came back a few months later with a different band and there was a huge brouhaha about the venue taking a merch cut because there was no internet, broken showers, and it was a shitty situation. He was pissed off about paying a cut for what were supposed to be facility upgrades. And he’s right! It’s like, what the fuck are you paying for when you have to prop up a three-legged table with a road case and hang a flashlight from a string for light?

“When people refuse to pay up, contracts are pulled out and everything is spelled out,” Peters continues, describing what happens when conflicts arise. “I’ve had some very nasty situations over merchandise, which is why I prefer to stay out of it, but it’s all in the contract and when I’ve honored my part of the agreement, it’s expected they honor their part. I’ve been in the middle of screaming matches between venue and artists, I’ve seen artists try and walk out and artists refuse to sell and end up selling from their van out back.”

“Since the merch percentage is often in the contract, it is hard for the band to argue around it,” says Netherton. “However, I have ‘seen’—not implicating myself here!—some bands hurry up and load out quickly in order to leave the venue before someone shows up to collect. However, it is often a stipulation that before getting paid, the merch cut must first be settled.”

Other times, the struggle over merch money becomes a lot more obvious and, as with most capitalist endeavors, the difference gets passed on to the consumer.

“If you refuse to pay, you can be banned from venue,” explains Netherton. “That will get back to the band’s booking agent, who won’t be happy, which will cause problems in that area as well. We have set up and sold our merch on the sidewalk outside rather than pay an insane fee, or raised prices only to make the fans pay more.”

“If all the venues continue this, it’s just going to lower merch sales and make the merchandise sold at shows not worth the price,” says Orion. “A lot of bands will say they then deserve a cut of the bar’s alcohol sales in exchange, but I believe these should be separate; the venue sells the alcohol, so they keep the money from those sales, the merch money stays with the band and the ticket money should go to the promoter.”

And then there’s Felk, who has her own personal struggle. “When I’m playing with the Genitorturers or selling merch for a band, I’m like, ‘Damn, I can’t believe these assholes are trying to take money from us.’ But when I’m at work, I’m like, ‘Damn, they better not run out of here before paying that money!’” she laughs.

The Future of Money

The merch cut is arguably the most hated part of touring for any touring band, but it’s become both an entrenched and unavoidable part of being on the road. Still, we wondered if anyone sees any change on the horizon. The practice is already arbitrarily enforced; percentages will vary depending on the venue and location, and some venues will randomly waive the fee or not have it in the contract at all to begin with. Bands aren’t likely to stop touring, but some might reconsider touring plans and routes if hefty percentages have to be taken into consideration alongside, for instance, administrative/management fees, the price of gas and disadvantageous currency exchange rates for those bands coming to the U.S. from Europe.

“Unfortunately, I don’t see anything changing because money is the only thing that matters to people who only care about money,” laments Sheridan. “We go on tour to play, get in front of crowds and further the progress of our band, but sometimes we’re playing for guys who only want to make a quick buck. They know they’ve got you by the satchel and don’t care about you, your comfort or the gas you have to put in your van. They just want their numbers. Until we get people who care about the industry and heavy music in general, then maybe there can be a discussion about changing it. But until that happens, I don’t see it going away.”

“We tried to get our booking agent to book a tour and not have us play venues that took merch cuts over 15 percent,” sighs Orion. “They started working on it and after a few weeks, they said it wasn’t possible. I don’t really see where it’s going, and there’s no simple solution. One thing we can do is to talk about it and to make people aware of the situation. What will people do with the awareness? I don’t know.”

“No, unfortunately I don’t see any change,” Peters says flat out, “because it needs to start at the top. That’s the arena level, and I don’t see anyone giving way to it because it is a revenue stream. Also, in places where governments are raising the minimum wage, that’s going to raise overhead costs [and] venues have requirements to have an audio engineer on hand, a certain number of security per square foot, property taxes, hydro and general operations for a place that’s open and holding events almost 365 days a year.”

“Like I said, owning a venue is hard,” agrees Felk, “and I’m sure none of this money is being pocketed by my boss for his own selfish endeavors.”

“Well, if any change is going to occur, it’s going to come from the bigger bands,” believes Netherton. “They’re the ones who carry more clout and are going to have to step up and negotiate with their booking agents to have the practice removed from contracts with local promoters and venues. Right now, because it is such standard practice and has this entrenched history, it is something which goes without saying, and those are the hardest practices and conventions to upend.”

This feature originally appeared in the March 2018 print edition of Decibel, which is available here.