Never mind that he funneled Bad Religion to Atlantic or facilitated in the harvesting of Opeth to Roadrunner. For the better part of Mike Gitter’s 24-year career in the music industry–at labels like Century Media (where he’s currently VP, A&R), Razor & Tie, Roadrunner, Atlantic–his beginnings as a small-time ‘zine editor of xXx (or xXx Fanzine) in the Boston area is often a hot topic. In the early ’80s Boston was a veritable well of hardcore and punk innovation, projecting first to the outer suburbs of Bean Town (where Gitter lived at the time) and next throughout the entire Northeast. Bands like SS Decontrol (or SSD), Jerry’s Kids, Gang Green, Negative FX, The Proletariat, and more were making statements and living by them. Gitter, with xXx, was there to see and document it all go down, either through personal relationships or through forced exposure to the new, the loud, and the purposed.

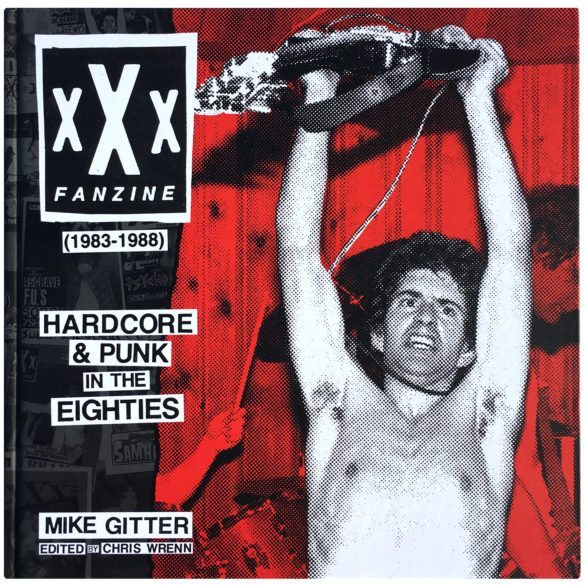

Fast forward 30-plus years later and Gitter’s reputation has passed from ‘zine editor to A&R guru. But that didn’t stop old friend Chris Wrenn from suggesting that Bridge Nine re-print and re-format the 20 issues of xXx in a hard-bound edition. Originally, the xXx project was slated to take no more than four months–so Gitter and Wrenn had planned–but the duo quickly realized the beast was larger than expected. What was supposed to be four months exploded into four years. Luckily, the scope creep helped xXx expand, deepen, and mature, in all areas. Gitter and team were able to procure additional photos, cultivate interviews with key players (re-interviews, basically), and improve the overall visual aesthetic of the book. Now at 288 pages, xXx Fanzine 1983-88: Hardcore & Punk in the Eighties is a major cultural milestone for not just hardcore and punk from Boston, but for the entire American scene, then and now.

We cornered Gitter to get a glimpse into his xXx past and what it meant for his future. Read on. (pre-order link at bottom of interview.)

For as long as we’ve known one another, we’ve never talked about ‘zine publishing or your involvement, going all the way back to ’83. That’s really cool. I’m not a big punk rock guy, but I appreciate and understand the sentiment behind xXx Fanzine 1983-88: Hardcore & Punk in the Eighties. It’s fantastic.

Mike Gitter: Right. It’s very dense. It’s a lot of information. We started the idea for the book about a decade ago. I don’t think anyone was more surprised than myself how resonant a fanzine that embodied the second generation of hardcore, punk, independent music, underground music—really was. So, I was approached by Chris Wrenn from Bridge Nine Records about publishing a book version. He had just finished the Schism [Records] book, and was looking for a second project. We discussed it. I sent him all 20 issues of the ‘zine. We were batting back and forth, debating if we were going to re-print all 20 issues, which I think no one really needs to leaf through that amount of naïve, but extremely raw, but extremely uninformed, but extremely heartfelt writing. It’s like every opinion you should have when you’re somewhere between 16 and 22. So, we were talking about the format. OK, let me start by saying xXx wasn’t Touch and Go [Records], it wasn’t Slash [‘zine], it wasn’t the cornerstone of fanzinedom. It wasn’t important enough of that era to validate a book. So, we started looking at it like a greatest hits project, re-printing some key interviews, key reviews, add some then/now commentary to flesh it out. We were thinking it’d be around 130 pages, taking around six or seven months to do. Four years later and an incredible amount of work—multiple life changes—and what felt like probably an immersion into being your own editor, we finished the book. It stands as 288-page, 11″ x 11″, nearly four lbs. hardback. It really took on a life of its own.

When I started “Requiem” with a good friend (who now is a Decibel illustrator), I had no contacts, no real exposure due to location, or experience. Mark [Rudolph] and I only had our CD collections, a bit of courage, and other ‘zines. We thought, “Hey, we can do this, too!” Is that how xXx started?

Mike Gitter: I’m lucky enough to have come from Boston. We had a lot of great bands in the early ‘80s. Not just a couple. Like seven or eight totally unique in our city, bands like SS Decontrol, The Proletariat, Jerry’s Kids, Gang Green, Negative FX, or The Freeze, who were from Cape Cod. Boston was also a college town, so we had seven or eight great college radio stations, like WERS, WZBC, WNBR, all of whom had dedicated and often daily punk and hardcore programming. Some of the people involved were Choke [Jack Kelly] from Negative FX and Katie the Cleaning Lady, who was one of the primary movers in a ‘zine called Forced Exposure. We also had a lot of great ‘zines. Forced Exposure was enormously influential to me. Not only did they have the Boston Hardcore Secret Handshake, but they also had the pictures that gave it a visual language, coupled with the influence of Glen E. Friedman first MY RULES fanzine. So, Boston had Forced Exposure, Smash!, Frontal Assault, Suburban Punk, which became Suburban Voice, which was my pal Al Quint. He was a hardcore big brother. He was an inspiration. Al is still a great friend. He now has a great radio show called Sonic Overload. The other thing that was important was I grew up two towns over from Lynn, Massachusetts. This is where SS Decontrol came from. Those guys and some of their friends were friends with guys in the Marblehead area. They were all notorious skateboarders. We also had guys like Tony Perez from Last Rights, Andy Strachan from DYS, and Jake Phelps, who was sort of the ‘town terror,’ who is now the editor of Thrasher Magazine. Having SS Decontrol in the background really was inspiring. There was a city-wide appreciation for that band. When I first put on The Kids Will Have Their Say that was the sound of complete liberation for me. With that, I realized I could create my own world, have my own voice, build my own scene, put out my own ‘zine, my own records. Basically, get involved, breaching whatever walls were there. I mean, music, culture, and art were no longer walled off. Hardcore made it ours for the taking. That was kind of the inspiration behind xXx. Also, getting a lot of free records was great. [Laughs]

The early days of xXx must’ve been interesting. Most of the struggle in ‘zine editing is trying to find the right tools to put it together. For Requiem, it was borrowing a friend’s word processor in the evenings or inheriting a Brother electronic typewriter. Did you have that with xXx?

Mike Gitter: We had a typewriter at home. My dad had a business in his house. As time went on, I discovered things like, “Oh, this is what happens to a typewriter font when you shrink it!” or “How did they do that—Letraset lettering—in Forced Exposure?” I mean, Letraset had to be perfect or you would have to do the whole thing over again. I remember learning about halftoning photos. As a young person, you don’t know barriers or boundaries. You have your imagination and you figure things out. As your ‘zine starts happening and you start selling copies, you suddenly have a little bit of cash. Like $40 to play with. That’s for the next issue. And so on. It snowballs pretty quickly. Al Quint and I were enormously helpful to one another. We’d give names of printers, photographers, and bands. In some ways, it was similar to the Bridge Nine, Deathwish, Hydrahead, the whole Initech Industries model that happened a couple of decades later. Al and I were down to help one another out. There was no cross-town rivalry. Both of our ‘zines benefitted from pooling our resources. The visual stamp of xXx was probably the reason why they responded to it. Photo covers were mostly black blobs of photos back then. Having really good pictures helped build xXx.

Right, totally get it. Back then, it was typing the text on a typewriter, carving out the text blobs with an X-ACTO knife, reducing the text on a copy machine, and then gluing everything down on a master or galley. There’s progression as you go up the issues in xXx. The first issue isn’t as clean and neat as the 10th. Lines started to get straighter.

Mike Gitter: That was exactly the process. It was discovery, refinement, really building a visual stamp over time.

But the cool thing about those days is you made it work. You didn’t have InDesign or before that Quark, a good scanner, a decent PC to process photos in Photoshop, or Illustrator to do text manipulation. Desktop publishing back then was pretty raw.

Mike Gitter: It was, but the beauty of it was getting in front of it. It was constantly a challenge to put forth a more readable, better looking ‘zine. It was tough to sharpen your skills back then. When I look at the first issue, it’s a mess! The ‘zine I did before xXx was called Suburban Mucus. We, or Mark Dincecco and I, did three issues. They were pretty clean and coherent. They were just as much new wave as they were hardcore. It was a snapshot of a kid coming off the sidelines and becoming a participant. The final issue of Suburban Mucus was probably a lot cleaner and more together than the first issue of xXx.

And xXx also evolved insofar as page count was concerned. Like most ‘zines. The first few issues are thin and then ambition kicks in. That or the inclination for more free music.

Mike Gitter: It does, doesn’t it? I would say xXx evolved from 16 to 32 pages by the end. Anything beyond that verges on book territory.

I love the book format. It’s almost like a 12” record. The big top photo with bottom text is a nice touch.

Mike Gitter: I credit Chris Wrenn with that. Chris has had a keen graphic eye for all that stuff you see in the book. You can see his work on Bridge Nine. He has a fantastic graphic sensibility. The book is a cross between being very dense yet being very readable. It’s very coherent, with its own visual stamp. Chris did a great job on all the material that’s in it. Some of the advertising, the posters, a preview ‘zine for the book. He’s maintained a sense of continuity throughout the project, which, of course, I really like. It evolved into a different beast from what it was originally envisioned. That’s why I also don’t regret it taking four years. This gave us time to really see what the book was. And it gave us time to collect things we didn’t have for the book, things—like photos—that weren’t in xXx that we wanted in the book. One of the great examples was a picture of Negative FX. This was taken at the band’s last show at the Bradford with Mission of Burma, who were also doing their final show. It was taken by a woman named Claire Sutherland. We went through Facebook trying to find her to get permission to use the photograph. It was like archaeology trying to hunt some of these people down. It was interesting because Chris Wrenn started to hunt Claire down through town registrars. We found her living in California, in a farm community. It was a complete bit of detective work. She referred Chris to her brother, who had a pile of her negatives and prints at his house. Chris went over there one day and scanned like 70-80 images. As it turned out, Claire went out with one of the guys in the FUs. She was a girl with a camera, going to college, who happened to be at the right place at the right time at really classic shows. She took some amazing photos. I would say her photos really upgraded the quality of the book.

Did you have the flipside? People immediately interested in the project?

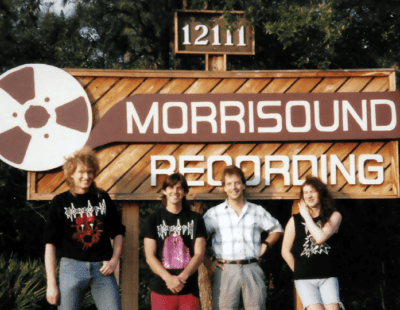

Mike Gitter: Believe it or not, yes. Like Henry Rollins. He got back to us in like 90 minutes with a quote. We must’ve caught him on a slow day. He was the second or third—to what became hundreds of voices—voice to contribute. Him and Ian MacKaye. I mean, I got on the phone with Ian to talk about ‘80s fanzines and labels. Fanzines helped spawn Dischord [Records], a label that helped change the nature of music. But I also had the opposite, like Reed Mullin, who is one of my oldest and dearest friends. He and I are born on the same day. When I was college, I’d spend time in Raleigh hanging with those guys. For one reason or another, it took us a couple of years to get together on the phone to talk about hardcore in Raleigh. So, I’m glad it took us as long as it did. We were able to gather and refine the content of the book.

The book captures the energy of the time. Professional magazines often lack that energy or are unable to capture it.

Mike Gitter: Thank you very much. I think it captures the honesty, the rawness, and the naïveté of a time, a place, and a musical revolution. In many ways, it’s changed the world. The impact of DIY America is pretty impressive. For example, there’s vegan options on flights. That was weird and segregated back then. But I think it was from a direct involvement by people in the hardcore scene. There are other factors, too, but the impact is felt. I mean, just listen to the opening moments of The Kids Will Have Their Say or Damaged. They’re a call to arms. They’re also an incredible inspiration to do it yourself. Change your world and the world around you. I’m beyond honored that there’s a book coming out in November based on something I did in my high school and early college years. I’m also honored that it’s being recognized as a small voice in a sea of change. I was one of many voices. The best part was we didn’t do it for any other reason than to do things on our terms, like any other art or sport or film or dance. For all of us who were—or rather are still—involved in the explosion of ideas and ideals in a music style that happened many decades, it was about fun.

What started out as a small endeavor had large impact over time.

Mike Gitter: For me personally, now having 24 years in the music business, there’s a lot of through lines. Whether it’s people, ideas, ideals, or music, it sprang from the early- to mid-‘80s. It all comes down to the sense of honest, visceral, raw art.

** xXx Fanzine 1983-88: Hardcore & Punk in the Eighties is out November 10th on Bridge Nine Records. Order this impressive and informative tome of ’80s hardcore and punk by clicking HERE.