(reprinted from our February 2014 cover story, written by J. Bennett)

That’s the way I like it, baby. I don’t wanna live forever.

—Lemmy, “The Ace of Spades”

Rumors of Lemmy’s demise have been greatly exaggerated. The story going around after Motörhead cut their sweltering midday set short at Wacken this past summer was that the legendary bassist/vocalist gave up the ghost that very night. And yet here he is, safely ensconced in his West Hollywood war bunker, surrounded by Motörhead regalia and Nazi artifacts, on the horn with Decibel: “I just couldn’t play anymore,” he says of the fateful show. “My back was giving me a lot of trouble. Kidneys, apparently. So, I had to hobble off. It’s a shame, really—we did 38 minutes. Almost made it.”

Almost is not a word that Lemmy finds himself using often. In his nearly 70 years on this planet—he was born on Christmas Eve, 1945—the outlaw artist formerly known as Ian Kilmister has done everything he’s set out to. After a stint hauling gear and scoring dope for Jimi Hendrix, he was famously booted out of Hawkwind in 1975 for doing the wrong drugs. So, he cranked up Motörhead and proceeded to conquer the world one shithole at a time, with one fist (iron, obviously) wrapped tightly around a bottle of Jack and the other hoisting a giant bird in the direction of anyone who got in his way.

He drank, snorted and rock ‘n’ fuckin’ rolled his way through the next four decades, writing the kind of stone-cold classics that most rock bands can only aspire to in fever dreams and fantasy headaches: “Overkill,” “Bomber,” “Ace of Spades,” “Killed by Death.” The list goes on and on. And on. He even wrote “Mama, I’m Coming Home” for Ozzy, which earned Lemmy more royalties than anything he’s written for Motörhead. There have been films made about him, books written about him, action figures fashioned in his mutton-chopped, mole-faced likeness. “People always ask me if there’s anything left I’d like to do, and one of them is that I’d like to get on the charts in the States before I die,” he says. “And now we’ve done that, too.”

He’s talking about Motörhead’s latest, Aftershock, which debuted at number 22 on the Billboard chart after selling 11,000 copies in its first week of release back in October. Of course, previous Motörhead albums have charted here, but none nearly so high. That Motörhead have managed to penetrate the upper echelons of pop-music hell with their 21st studio album—after nearly 40 years of deafening, remorseless motherfuckery—is a testament not only to the band’s reliability, but to the quality of Aftershock itself.

“This is a much, much more diverse record than usual,” Motörhead drummer Mikkey Dee tells us from his pad in Sweden. “I haven’t been the biggest fan of albums that vary as much as this one, but this one turned out okay, you know? Some of our older albums, you have 12 or 14 songs and there’s not a red thread between them. Those albums don’t turn out as good. This one has that thread.”

“This one is different because I almost made them do the record twice,” says Cameron Webb, who has produced the last five Motörhead albums, starting with 2004’s Inferno. “The first time around, we did 10 songs, and I told them some of the songs weren’t good enough, that we needed to do some more. We disagreed and disagreed, but then we actually had to fly [guitarist] Phil [Campbell] and Mikkey back out for a second round. I said, ‘We’re gonna go into a studio and write songs. When I hear something that’s good, we’re gonna hit record.’ So, I basically had them write a song a day for seven days. Part of that process was me telling them they needed to be more pissed.”

Which begs the question: What’s it like telling Lemmy and Motörhead that their songs aren’t good enough? “When you work with a band like Motörhead, they have a certain way they wanna do things—they have a path that they’re really good at walking, and you have to respect that,” Webb acknowledges. “But they also have a side where they don’t see what they really need to do, because they just do it the way they always do it. That’s where people like me come in.” He laughs before delivering the punchline: “I risk getting fired everyday.”

“When I told Motörhead they needed some faster songs on this record, at first they told me, ‘Fuck you, Cameron,’” he concedes. “But you have to push a little. Sometimes they’ll tell you no, and sometimes they’ll walk out of the room. Mikkey told me that I’d ‘lost my marbles’—and that was just because I wanted him to try out another drum part in the bridge of a song. So, we argued for about two minutes over the talkback before he storms out and tells everyone in the band that I’m crazy. But finally he comes back and says, ‘I’m gonna give you one more take, and that’s it.’ And you know what? He did an amazing part in that bridge. But you can’t be scared of people just because they’re successful or, you know, mean-looking. If they’re professional, which Motörhead are in a weird-ass way, they’ll respect you more for standing up to them.”

DAMAGE CASE

Chazz: Who’d win in a wrestling match, Lemmy or God?

Undercover cop: Lemmy.

Rex: Wrong. Trick question, dickhead. Lemmy is God.

—Airheads, 1994.

Despite Aftershock’s success, the prevailing tone in Motör-land is not exactly champagne and roses. The band had to cancel their November/December European tour due to Lemmy’s ongoing health problems. Since being diagnosed with diabetes in 2000, he’s had to have a defibrillator installed in his heart, and more recently suffered from an “unspecified hematoma,” which led to the cancellation of several European shows last summer. Factor in a daily intake of smokes, speed and Jack and Coke for the last 40-plus years, and it’s a wonder he’s alive at all. After decades of invincibility, the cracks are finally showing. Lemmy has had to make some difficult adjustments. “I had to give up the Jack and Coke because of the sugar,” he tells us. “I miss it. I gave up smoking, too. I gave up bread. It’s been a bit of a job, you know?”

“He’s been up and down,” says longtime Motörhead manager Todd Singerman. “He’s got a really bad diabetic problem, and it changes on a daily basis. A lot of it is just fighting the bad habits, the things that he’s not supposed to do anymore. He’s stopped smoking, but he probably sneaks Jack and Coke here and there. He’d be lying to you if he said he stopped. He’s been trying to substitute it with wine, and I’m sure he’s slowed down on the speed. He thinks wine’s better than Jack, but it’s still got tons of sugar, you know? He doesn’t grasp that he’s just trading one demon for the other. That was the compromise with the doctors, by the way—trade the Jack for the wine. But he doesn’t tell them he’s drinking two fucking bottles, either. These are the battles we’re up against. Keep in mind, he’s been doing all this stuff on a daily basis since Hendrix. And it’s coming to roost. It’s sad for him, because he’s gotten away with this stuff for all this time.”

And therein lies the crux. For any other 68-year-old, declining health would seem like a natural, even expected course of events. But Lemmy has the reputation of being invincible. “Lemmy is God,” the saying goes, and Motörhead do not cancel shows. “We knew it would be a huge disappointment for our fans and for us as a band,” Dee explains. “Lem is more disappointed than anyone—but we went over the good and the bad, and in the end we decided to postpone. It’s much better to take it slow. We’ve been touring so much over the years, and this is the first time that we actually did anything like this. I think Motörhead has worked up the credit to postpone a tour for once. Lemmy is 68, not 38, you know? When he doesn’t feel good, it’s gonna be worse for him than it would for a 30- or 40-year-old person. And we all know how hard he lived over those years, so it’s better for him to come back 100 percent instead of this shit happening again.”

“I made them cancel it, because Lemmy’s not ready,” Singerman explains. “He didn’t wanna cancel. But what was gonna go down is what happened in Europe over the summer. See, he fucked up in Europe. He was supposed to rest for three months, and he refused. He ended up doing that show [Wacken], which he wasn’t supposed to do, and it ended up being 105 degrees out there. He’s playing direct in the fucking sun. The only thing I’m proud of him for is stopping when it didn’t feel good. That was smart of him. The bottom line is that he needs to find a balance and then live that balance for a few months. But we can’t find the balance yet. He has great days and then he fucks it up. And when you fuck up, you go backwards.”

The European tour has been rescheduled for February, with a U.S. tour to follow in March. Meanwhile, Lemmy languishes at home in West Hollywood—resting and waiting. He doesn’t like sitting still for this long. “It’s kind of a drag,” he says. “You get into the mindset of four walls. And that’s bad. Still, optimism is the key.”

We ask if he’s been able to keep his spirits up. “Uh… kind of,” he replies. “I’ve been reading a bit. It’s one of the only things I’m allowed to do. I’m reading a book about the Kinks at the moment. I re-read a couple of Len Deighton books. And I read a book about Little Richard.”

We ask if he’s been able to play any music since he’s been home. “No,” he says, with more than a hint of sadness. “I’m just doing my best to get fit.”

He mentions that his son Paul comes over quite a bit. Then he has to take a piss. “Do you have two minutes?” he asks. “I have to go to the bathroom.”

The truth is, Lemmy doesn’t sound so hot. He sounds tired and out of breath. His replies are brief, not because he’s trying to be short with us, but because it seems like it’s all he can muster. Ten minutes in, we feel guilty even having him on the phone. As it turns out, Dee spoke with him the same day we did. When we suggest that Lemmy sounds pretty awful, he knows exactly what we’re talking about. “It’s because he sleeps a lot,” Dee offers. “If you get him when he’s just woken up, he doesn’t sound good. He huffs and puffs and sounds really slurry. I don’t know what time you called, but that is the difference for sure. When I talked to him, he sounded fine.”

When Lemmy returns from the pisser, we ask if he’s been able to drop by the Rainbow Bar & Grill, the legendary rock ‘n’ roll watering hole where he’s been a fixture since taking up residence just a few blocks away in 1990. “Oh, yeah—I still go down there,” he says, brightening for the first time since we started talking. “I’ve been going there for a long time, you know. ’73 was the first year I went.”

What else has Lemmy been up to? He doesn’t exactly seem like a computer kind of guy, but as it turns out, he totally has one. “He does, but it took him forever to get one,” Singerman says. “He actually has an iPad, but he just uses it for the gambling games. He’s not gonna go on there and tweet, that’s for sure.”

Oh, and picture this if you can: Lemmy on an exercise bike. “I don’t use it every day, but most days,” he says with a laugh. “I never imagined having one, but there’s a lot of things that happen at this age that you couldn’t imagine before you got here.”

MARCH ÖR DIE

The first time Lemmy asked Mikkey Dee to join Motörhead, the drummer turned him down. That was 1987, when Dee was drumming for King Diamond, who had recently completed an early tour opening for Motörhead. “It wasn’t because I didn’t like Motörhead,” Dee recalls. “It was because I personally felt that I didn’t have the stripes to join a band like Motörhead. After touring with them, I got a huge look into how their fans are and how big an institution they actually are. It was not just like joining a regular rock band. There’s a few bands out there—Motörhead, AC/DC—that have a following you can’t really describe. I was also very happy with the King Diamond band, so I was glad I turned him down.”

Lemmy called again in 1990, just after Dee had signed on for an 11-month tour with Don Dokken, who had recorded a solo album in the wake of the band Dokken’s demise. Dee was forced to turn Lemmy down again. But the third time was the charm: “When that tour was over, the Don Dokken band kinda fell apart,” Dee explains. “Lem called me again, and it was perfect timing, so I took it.”

At that point, Motörhead already had most of what would become 1992’s March ör Die in the can. Longtime skinsman Phil “Philthy Animal” Taylor managed to play drums on just one song—the quintessential Motör-ballad “I Ain’t No Nice Guy,” which also featured a solo from Slash and additional vocals from Ozzy. All the other drum tracks were handled by former Ozzy/Whitesnake/Black Oak Arkansas drummer Tommy Aldridge.

But Motörhead had been commissioned to write two songs for the upcoming horror flick Hellraiser III, which is where Dee would make his recording debut with the band. One of those tracks was a re-recorded version of “Hellraiser,” a song Lemmy had originally written for Ozzy (a different version appears on Ozzy’s 1991 album No More Tears)—and would make the cut for March ör Die. “The main thing I remember about that session is that we had to run for our lives because the [Rodney King] riots broke out in L.A.,” Dee recalls. “I had just bought a brand new Corvette, so I was freaking out because we were in Hollywood and the riots kept moving closer and closer to the studio every hour. At one point, we said, ‘We gotta fucking go.’ So, we took off.”

Which seems like a fitting introduction to Motörhead. “I know!” Dee laughs. “Welcome to fucking chaos, right? It was perfect. Unfortunately, the riot was such a sad thing. But looking back, it was a good welcome party for Motörhead.”

Oddly enough, Singerman signed Motörhead to a management deal the very same night. Before that, he’d worked in politics, managing campaigns for California state senators and assemblymen. “A friend of mine was an attorney who worked with a bunch of rock bands, and at some point I heard Lemmy needed a lawyer because he was pissed off at Sony,” Singerman explains. “I didn’t really know who Lemmy was at that point, but I knew the name Motörhead from seeing the guys from school, sorta the mechanic guys, wearing the T-shirts.”

Singerman ended up going to Lemmy’s place with the lawyer friend. “I guess at the time Lemmy wanted to get rid of his manager,” Singerman says. “He liked that I didn’t seem to bullshit people, so he told me to stick around. I had no experience managing a rock band whatsoever. I remember they were doing March ör Die, and the label called me for album credits. I was like, ‘What the fuck is that?’ I had no clue. But I dealt with it as it came, and I learned that it’s not that much different from managing a campaign. A campaign is a very targeted message, and Motörhead has a very targeted message.”

Before Cameron Webb met Lemmy for the first time, Singerman sat him down at the Sunset Marquis in Hollywood. This was 2003, when Motörhead were on the hunt for someone to produce the album that would become Inferno. “Their manager said, ‘Cameron, you’re a nice guy. I don’t even want you to be part of a Motörhead record. It’s just too rough,’” Webb recalls with a laugh. “But I told him I wanted to do it. So, I met Lemmy and told him that I wanted to make a really big, thick, heavy-sounding record. And Lemmy goes, ‘Cameron, we’re not a heavy metal band. We’re a rock ‘n’ roll band.’ And right there I was like, I fucked up. After the meeting, the manager goes, ‘You only made one mistake, you dumbass.’ And of course that was it: Don’t ever say Motörhead is a heavy metal band. But I got the call the next day saying I got the job.”

THE MOTÖRHEAD WAY

Lemmy is telling us about the time he got a blowjob onstage. This was back in ’75, he thinks, the very early days of Motörhead, when the lineup included former Pink Fairies guitarist Larry Wallis and future Warsaw Pakt drummer Lucas Fox. “I wore my bass a bit higher back then,” Lemmy offers when we ask about the logistics of such an act. “And she got in behind it. It only happened the one time, unfortunately.”

Of course, Lemmy’s exploits—the drugs, the booze, the women—have been endlessly documented in magazines, in documentaries (like 2005’s Live Fast Die Old and Motörhead: The Guts and the Glory) and in his thoroughly entertaining 2004 autobiography, White Line Fever, a book he describes today as “halfway dodgy.” But it was the 2010 documentary Lemmy: The Movie that made our man and Motörhead practically mainstream. Suddenly, Spin and Rolling Stone were doing features—the latter even writing about one of Lemmy’s handlers negotiating with a prostitute for him in front of his apartment building. Next thing you know, Motörhead are on the Conan O’Brien Show and Late Night With Jimmy Fallon. “All of a sudden, we got known,” Lemmy acknowledges. “It was no problem for me—I live in L.A. anyway, so I always get spotted. But the other guys said they weren’t in it enough.”

Dee’s perspective is a little different. “I can’t say anything changed,” he offers. “Maybe Lem got some more credit for certain stuff, and I’m glad that he did. He deserves it. But overall? No. I mean, this band does not operate like other bands. I remember when we did the Jay Leno show in ’92 or ’93, right after I joined the band. People told us that just by playing the show, our album sales in the U.S. would go through the roof for the next week or two. But we actually sold less after we played! I’m proud of that. That’s the charm of this band. We’re like Spinal Tap with no script.”

As every good mötorheadbanger knows, the band has been through many a lineup over the years. There’s the classic Lemmy/Philthy Phil Taylor/Fast Eddie Clarke lineup that recorded the first five albums; the short-lived Brian Robertson era that produced the excellent but controversial Another Perfect Day; and of course there’s the twin-guitar lineup featuring Phil Campbell and Michael “Würzel” Burston that debuted on the cult British comedy The Young Ones and would go on to record such middle-period juggernauts as Orgasmatron, Rock N’ Roll and 1916.

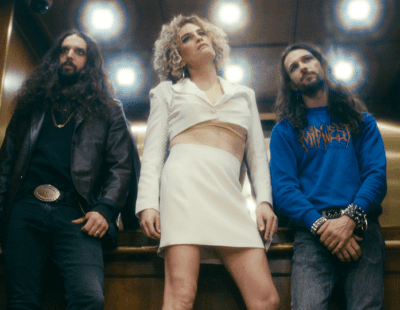

But it’s the Lemmy/Mikkey Dee/Phil Campbell lineup that has lasted the longest and recorded the most albums. “It’s good machinery, if you will,” Dee ventures. “We get along great and play well together. We respect each other tremendously, of course. The three of us are so different, yet somehow the same. I mean, we are so different, but when it comes down to it, we have the same passion and the same rock ‘n’ roll vibe. There’s not a fake bone in anyone’s body here. We’re all on the same page as far as how we should present the band and move the band forward. There’s always some money-hungry bastard in every band, someone who is willing to sell out, and that actually tears bands apart—these guys that would sell their own fucking mothers to gain album sales. In this band, that’s never been an issue. We do what we like, and that’s it.”

Which brings us back to Aftershock: As good as it might seem to Decibel, Dee and the 21,000 or so U.S. fans who have laid out their hard-earned cash for it as of press time, someone is sure to complain. And that someone will probably be German. “Every album we do, we get people who don’t like it,” Dee laughs. “They come up to me and say, ‘This album fucking sucks!’ Especially in Europe, because you have these hardcore freaks—Motörhead is such an institution for them, the lifestyle and everything, so when the album comes out and it’s not to their liking, they get so disappointed. Sometimes they think it’s too metal; they want more of the bluesy rock ‘n’ roll. And for others it’s not metal enough.”

“But they are truthful to us,” he adds with a chuckle. “They don’t kiss our ass. Sometimes I have to be like, ‘C’mon, buddy. You don’t have to kill us for making an album that isn’t perfect for you.’ If we sat around a table and tried to write a record that everyone would like, we’d end up with 200 songs and people would still complain. And the same goes for a live set. There will always be people who wanna hear more old stuff, and then younger kids who ask why we don’t play more new stuff. But that goes in one ear and out the other. We decide this shit, you know? If you don’t like it, piss off.”

OVERKILL

Faced with the first substantial lull in Motörhead’s touring career since the band started, Lemmy is contemplating a future in which they no longer tour at all. He’s dropped hints, some subtle, some not so subtle, that Motörhead will become a band that limits their activity to the studio. “Yeah, that’s what it’s looking like,” he tells us, before trailing off into silence.

We look to Dee for clarification: “Well, maybe not tour as much,” he offers. “We’ve talked about this for 10 years. Right now, Lem’s confidence is gone. You have to keep that in mind. His self-confidence is completely gone. I hear it when I talk to him, too, because he never, ever thought this day would come. He never thought he would fall apart the way he did this summer. He never thought he had to take care of himself. So, he’s going through a transformation. He has to take care of himself much better than he has for the last 67 years. So, that’s why his confidence and his mood is not where it should be. We can definitely go out and do shows, but what we can’t do is continue on the path we’ve been following.”

That path has been a grueling one by anyone’s standards. “Our schedule has been so insane for the last years that if we were late flying out of Washington, D.C., we would maybe have to cancel a show in Frankfurt,” Dee explains. “If we were late out of Madrid, we might have to cancel Sao Paulo. So, it’s ridiculous. We’ve been doing 23 shows in the U.K. alone. There’s no reason why we should play in everyone’s backyard. Instead of that, we could easily do seven shows in the U.K. Instead of 15 in Germany, we could do five or six. We can pull a week here and a week there, and suddenly our tours would be half as long. We can put a few more days off in between to make it more comfortable. I mean, I complained about it more than Lem and Phil, because I felt I couldn’t recharge enough between tours. I gotta feel that it’s fun to tour, but I got to the point where I just didn’t like it. I put out an enormous amount of energy every show, and after so many shows you really need to change the fucking battery. It’s not enough to recharge it because it’s worn out.”

To hear Singerman tell it, what the future holds is ultimately up to Lemmy. “He really has a long life to live if he just changes his lifestyle,” the manager ventures. “And it’s not just the booze and other things. He doesn’t eat right. He eats deli stuff out of the backstage, and that’s what he eats when he’s at home, too. We gotta get him eating right. I had a chef go over there, but he fired her after two days. He didn’t like it because she didn’t put the salt in there and all the shit he likes. And I’m telling him, ‘That’s the point, Lem!’ But he got mad and fired her. So, I’m sitting him down with a nutritionist in the next couple of weeks so he can give her a menu of the stuff he likes and hopefully she can figure out a healthy way to do it.”

Well… blueberries are healthy, right? That’s what Lemmy thought, too. And they are. Unless you eat too many of them. Which he did. “We found out that he was literally OD’ing on blueberries,” Singerman says. “Who knew you could eat too many? But you can. They store too much water. We looked it up and found out that bears eat blueberries before they go hibernate for that very reason. But we don’t need Lemmy to store water because he bloats. The poor bastard thinks he’s doing good because he’s eating blueberries, you know? But whatever he uses, he abuses. So, we had to have an intervention over the berries. We actually had to have the doctor talk to him.”

Then again, it’s probably a miracle that Lemmy is even alive to OD on blueberries. “Honestly, the first Motörhead record I did, I thought it would be their last record,” says Webb. “Just seeing the way those guys [are] live. But that was 10 years ago, and we’ve made five records in that time—and as many live DVDs. I don’t even know another band that has made that much stuff in that short amount of time. It’s insane.”

“We don’t give up. We don’t stop,” Singerman concurs. “I’ve never had a vacation, because Motörhead never stops. They make a record, they tour, and then they make a new record and tour again. Of course, it’s slowing a tad here, but we’re already confirming the summer festivals in Europe and we’re putting together a tour for March here in America. So, he’s got a full schedule if we can keep him healthy and off all the shit. But he wants it. He’s not comfortable if he’s not on the road, because that’s really where he lives. He’s frustrated, you know? But when you abuse your body for over 40 years, it’s gonna take time to heal it. But he ain’t going anywhere, I’ll tell you that.”