To paraphrase the demon that once mauled Albert Brooks in his own car on the side of a darkened road back in ’83: Hey, d’ya you want to hear something really scary?

Yeah? You sure?

Alright, then, Fangoria Musick — the exquisitely eclectic, ceaselessly unsettling new digital download music label from the legendary flagship magazine of dark cinema and culture — is here to whisper (and sometimes scream!) not-so-sweet spine-chilling somethings to you through those innocent looking earbuds of yours.

“A lot of bands out there that are good at math — they’re like the telepods in The Fly,” Fangoria Editor-in-Chief Chris Alexander tells Decibel when we inquire just how in the hell he managed to summon one of the best labels in sinister cinematic music seeming out of the ether in less than two months time. “They go in one side and come out the other exactly the same — information regurgitated exactly as inputted. You can reproduce anything, but if there’s no stamp of originality…what’s the point? We’re looking for those bands that get the fly — whatever that may represent, musically — mixed up on the journey and create a completely new beast.”

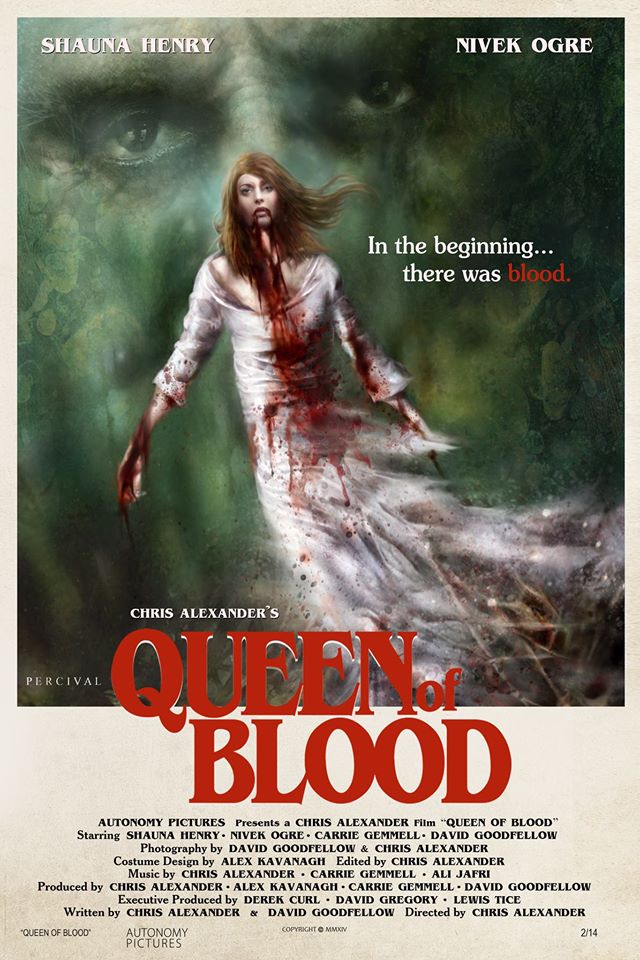

Alexander knows more than a bit of which he speaks: Aside from his kinetic, distinct writerly salvos, the modern day Renaissance man creates both music — the glorious, kaleidoscopic 2012 mindfuck Music for Murder and its worthy, 100 percent free Fangoria Musick successor Beyond the Darkness: An Audio Nightmare — and ethereal, otherworldly films — Blood for Irina; the upcoming Queen of Blood — that truly earn the typically too-freely given accolade “boundary-pushing.”

Oh, yeah, and dude also once boxed House of the Dead director Uwe Boll…

Alexander was recently kind enough to take some time out of his busy schedule to chat with Decibel about the launch of Fangoria Musick, his own work as a composer and filmmaker, and the joys of getting Ogre from Skinny Puppy to vomit blood in the woods on command…

You only put up the call for submissions a few weeks ago — are you surprised at all by how quickly you were able to put together such a high quality stable of artists?

I suppose I was taken a little off guard by how much cool, weird stuff came in. I presumed I’d be getting a lot of third-rate rock n’ roll bands with a bunch of skulls painted on their guitars singing psychobilly songs about Dracula rocking out in a tomb or something. That’s not scary; that’s not horror. So for someone whose personal tastes lean more toward the abstract and atmospheric — in both music and cinema — to have people sending me all this really interesting avant garde stuff has been just great.

That last statement is only a tiny bit ironic coming from a guy harboring such an outspoken love for Kiss!

Well, to me, Kiss is just as much circus and cinema as it is music: It’s a cult thing. And I listen to and enjoy a lot of different kinds of music — everything from Jim Croce to the hardest industrial noise. But when it comes down to the so-called serious art I prefer Aphex Twin and Skinny Puppy. That’s where my heart is. I mean, one of my favorite albums of all time is the soundtrack to the Alan Parker movie Angel Heart. The CD is just one long track — it’s almost like a dark dream state version of watching what is essentially a dream state movie. As a kid I was completely fascinated by that record and it really influenced the music I listen to and the music I write.

Can you give me kind of a thumbnail sketch of the Fangoria Musick origin story?

Fangoria doesn’t do a lot of music coverage, but since I took over five years ago I’ve worked to ensure music is much more of a character in the mag and this is a way we can get a little bit more into the music game in a way that serves our readers. The way we’re promoting it is as the ideal soundtrack to the magazine — here is some music that makes sense to blast while you’re reading the mag. And it can make sense: I was a book and record junkie when I was a kid. Power Records was my life. Before I saw any Planet of the Apes movies I listened to my Planet of the Apes books and record set to death. Actually, it took me awhile to get into the groove of the Apes movies because I was so used to the Power Records version. So I love the idea of someone picking up the latest Fango and streaming something off Fangoria Musick and having that sort of interactive experience.

How long did the idea percolate before you moved forward with this format?

Six or seven years ago when I was freelancing for Fango I offered up an idea along these lines — it wasn’t download, because that technology was still in its infancy; but the concept of some sort of supplemental music label was the same — and it didn’t fly back then for whatever reason. So it’s always been in the back of my mind. The actual creation of this particular incarnation of the idea, on the other hand, was literally the result of a ten minute brainstorm. I thought, Wait a second…we’ve got this name; we’ve got this website — we can do anything with it if we’re willing to set up the machine make it happen. So we put the call out. My album was already recorded and ready to go the next day. A couple days after that we signed the first act. It was all very, very, very quick and now we’ve had over two-hundred and fifty submissions. The idea is to sign a new act each week and offer people a really wild selection of crazy, crazy artists at a really cheap download price.

It’s a pretty amazing opportunity for bands making the sort of eclectic, dark music that otherwise might very well not find a home elsewhere…

Yes! And while no one is going to make any real money off of this, hopefully we can help create a new community of musicians who are doing interesting work. I don’t do what I do for money, anyway — and thank God, ’cause there isn’t a lot of money in this game. I do it because I love it. To be able to offer the power of the Fangoria name to these bands that otherwise wouldn’t have an in with our readers…that is a real pleasure.

I was really taken with your 2012 album Music for Murder and Beyond the Darkness is a deliciously sinister evolution/follow-up. It’s all really off-the-beaten path stuff, so I’m curious about your arc as a composer…

When I was little my dad played guitar and also exposed me to a lot of great music. He used to put the headphones on me so I could really take in Jimmy Hendrix’ Are You Experienced. Actually, there’s a 8 mm film of me at three years-old punching the air left and right in front of the stereo speakers along to “Third Stone From the Sun.” So music was always part of my life. And I always loved the idea of playing guitar; loved the sound of it. But I’m not a particularly disciplined person in the sense that if I want to say something I say it. If I want to do something I do it. By which I mean, I didn’t really have the patience to learn chords. [Laughs] So [my father] tuned the guitar open for me and I used to play it on my lap with my thumb, power-chording my way through everything, just eager to start creating right. then. I think that’s an approach and philosophy that has, for better or worse, carried through to all that I do. As a musician I’ve developed a sound using certain warmer, analog ways of recording and sometimes more difficult to navigate instrumentation. There are absolutely easier ways to go about it, but I’d rather take a more primitive route if that’s what it takes to make sure my music maintains a sense of humanity. When I’ve dicked around with digital it has created a sameness that robs it of its personality. I prefer the flaws and struggles.

I recall an interview with you where you talked about all your different avenues of expression — music, cinema, writing — as essentially music. Is that still the case?

Oh, absolutely. I never saw a difference between using words as notes, using notes as notes, and using image as notes. In all forms of communication its about rhythm and timing and hooks and repeating themes. When I was in college shooting on 16 mm — that’s all we had — I would cut my movies by desk lamp with a pair of scissors frame by frame by frame; each frame representing a beat to me; a note. If I got it right, when you watched it later there would be a rhythm to the film. The goal, then and now, was to answer the question: Can you hear the music watching a silent movie?

So much of what separates a good artist from a great artist, whatever the medium, is transition, flow, how they employ nuance — right?

Sure. There are a lot of indie filmmakers out there right now — too many. I see a lot of these films and to me the deal-breaker isn’t the budget or what they lack in equipment. It’s the tone deafness; the way the film is cut. They don’t know when to pull back. They’ve got explanatory dialogue here and gore spurting there — all the elements are in place, but they simply don’t know how to put it together in a musical way. I don’t think that’s because they’re dumb human beings or don’t know their cinema, I think some people just don’t have the innate sense of rhythm. They don’t have the music.

Meanwhile, your film Blood for Irina — which you both direct and score — essentially turns the usual music-to-visual quotient on its head.

That’s actually why I’ve made two movies — not to be some sort of amazing director, but to create images to go with my sounds. My movies are visual experiences — there is no dialogue — which gives me an excuse build all these new portals for myself into my own sounds even as I offer up the final cohesive whole to other people in a different form.

Was that always your vision for the film?

To be honest, I did the music first because it was supposed to be a much bigger project. There was, at first, a guy who came along and said he could get me quite a bit of money to make the movie and when I get excited about something I’ll always be like a kid — impatient. I don’t like to wait. I like to move on things right away. So I created music to go along with this script I wrote and by the time I realized there was no money I was like, “Well, fuck. I still want to make a movie!” I cobbled together literally no money and made a smaller, more intimate version of what I originally planned re-imagined and reshaped around the way I felt about the music that already existed.

And the upcoming Queen of Blood is an extension of that approach?

Yeah. I sort of wanted to make the vampire version of Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God, and, so, I wrote a theme that reminded me a little bit of the late, great Popol Vuh’s work on Aguirre and let it evolve from there. Sometimes you take old pieces from your library and pervert them and crossbreed them with something else and that process takes you somewhere you previously never would have imagined going. Film just adds another dimension to that experimentation and journey.

It’s an cool, subtle shift of emphasis, considering how integral sound work is to horror cinema.

I think most horror fans are sophisticated enough to realize that. You know, it’s funny, I have three kids, and they’re starting to get to an age where we can talk about a lot of ideas and dissect movies and music. It’s a lot of fun. Not long ago I put the John Carpenter Christine soundtrack on in the van. I’m driving along and they love it –- they’ll sing the sounds; band the back of the car seats in time with the beat. I say, “Alright, we’re just going to cruise around the suburban streets here, okay guys?” I turn down the music. “Hey, look over there!” We pass the park. They get all excited, ’cause that’s a happy, fun place. And now we turn Christine up and circle around, driving by slow. I tell them to look at that park now and tell me how they feel. “We’re scared of that park now!” I’m like, “I know! Me too!” Why? Because music completely scrambles your brain and alters the way we view things. And that, of course, is key element to the success of any horror film. It’s all intertwined.

Is it an interesting writing prompt for you, then, when you’re asked to score another film?

Actually, along those lines, I did a full soundtrack for an upcoming movie called Devil’s Mile by a guy named Joe O’Brien who used to write for Fango and Rue Morgue. I’ve known him for ten years. It’s good stuff — a supernatural crime thriller-type thing. Anyway, they came to me and said, “We need a score in two weeks.” Now, that’s kind of crazy — I run three magazines; I have three kids. But I don’t like turning down opportunities to do cool things so literally what I did was, I’d put the kids to bed then sit there with my tiny little four track in front of the TV watching the time coded version of the film and making these tapestries of sound all night in a hazy ultra-tired state. I push myself to finish things and what I ultimately submitted to them was a ninety minute track that was timed to every second of the movie.

Tailor made!

Right, but here’s the point: At the beginning Joe had said to me, “I’m thinking Goblin meets John Carpenter. And I said, “Okay, then what you want is Big Trouble in Little China meets Contamination.” Long pause. “I guess so.” [Laughs] But, though he was under plenty of pressure, he didn’t hold my hand or watch over my shoulder. He and the producers just left me alone for two weeks to get down my impression of his movie. There were certain scenes that I thought maybe weren’t scary enough, and I thought, “Well, if we do this here it might change context of this scene; maybe give it more intensity” or “What can I do to bring the melancholic, emotional aspects of this moment out a little more?” At the end of all this Joe told me, “I’ve been working on this movie for two years and even I didn’t know all these things were there until you put the music on top of it.” The soundtrack had brought something entirely new to the surface for him. That is the highest compliment he could pay me because that is how any fruitful relationship between a composer and a filmmaker should work — it shouldn’t be about dictating thing but playing off one another and exploring new ideas as they come up.

It’s a unique set of circumstances that really couldn’t be replicated any other way…

Right. And, actually, I recently listened to that Devil’s Mile soundtrack for the first time in a year. It’s just this wave of weirdness I don’t remember making ’cause I was in a total dream state while I was doing it. That’s a pretty cool way to become reacquainted with your own work!

Earlier you name-checked Skinny Puppy as a major influence and I’ve read Ogre is going to be in Queen of Blood. What’s that like for you?

It’s a high point for sure and also…incredibly surreal. There is such a discrepancy between the way I do my work — alone, in a home office — and the reality of how it ultimately fits in the world. For example, take Fango — for me, as a kid, Fangoria was mythical. I was raised on this magazine and it is no doubt a huge part of why I love such weird shit today. And, yet, I can forget sometimes in the day-to-day craziness that this is really real — that my job is to make this magazine and be a part of that insane 35 year history. Likewise, I’ve known Ogre for several years in the sense that we’ve talked, we’ve done interviews. But we’ve never really hung out. I knew Ogre wanted to do more acting — and he should because he’s such a great presence! — so I told him I was making a movie for nothing, but if he wanted to be a part of it I could fly him how to Toronto and pay his wage for the day. He agreed, which was awesome, but, again, it didn’t actually become real to me until I’m in my car and I realize, Fucking no way — I’m going to pick up Ogre from the airport and I’m taking him to my house and dressing him up like a preacher and now he’s eating sushi in my living room and soon we’re going to go into the woods where this guy who used to scare the shit out of me as a kid is going to vomit blood in the woods for me! It’s pretty amazing. Then, a couple months later, I go see Skinny Puppy and there’s Ogre on stage, suddenly alien to me again, and I’m just a fan of Skinny Puppy watching this guy command a crowd that I’m a part of. That’s when the relationship I have with this world can start to seem really surreal and strange — which is great!

One thing that strikes me as I read your editor’s notes and interviews is how, in a culture of whining and entitlement, you exude this kind of effervescent gratitude about your definitely-pretty-awesome lot in life. Is that something you cultivate?

Well, how could I not be grateful? At the same time I can tell you that for every person who likes what I do another person who tells everyone I’m a cunt and I don’t even know why. Just the way life works, I guess. That was the one unpleasant shock of it all when things started to go pretty good for me: Once you’re out there, just being yourself — the self you’ve always been — you have to contend with the fact that some people are suddenly going to cultivate a dislike of you. It’s a very strange thing to get accustomed to. And I don’t want to sound egomaniacal — I’m genuinely not — but I do know this is true because I have encountered people like this my whole life: Some people don’t work as hard as they should and when things don’t go right for them they want to take it out on someone else. It’s just the way it is.

That’s an old story, no? Everybody loves the hometown band until they get signed.

We hate it when our friends become successful, etcetera.

Morrissey missed out on a real opportunity himself, leaving off that “etcetera”!

Maybe! The truth is, I get some seemingly impossible things done. But it’s not without sacrifice and not without behind the scenes super-drama and not without worries with finances. It’s a struggle. You know, people always wait for their ships to come in. A know a lot of guys who are bitter about life who will spend a lot of time sending out one boat. They’ll make that one boat fucking beautiful and perfect and it’ll shine. It’s a nice boat, but they sit around waiting for it to come back and its already crashed on the rocks. It’s never coming back. And they’re so downhearted about that they’ll just give up. Then they’ll see me have a couple ships come back in and it’s like, “That fucking asshole! Must be doing something insidious. His boats weren’t even that great!” Well, the difference is I send out a fleet everyday, so the odds are a couple will come back. That’s the way I see it. The success I’ve gotten is hard earned. I’m always, always, always working. I’m always putting myself out there. I get the word No thrown out me way more often than the word Yes, believe me. The editor of Fangoria only means something to a small number of people in the larger scheme of things. To others horror is a gutter thing. Why would you waste your life having anything to do with horror?

As someone who has sent out so many ships, it must be pretty gratifying to have this platform from which you can shine a light on the work of a band or filmmaker or author you find intriguing or worthwhile…

Oh, it’s incredible to have a job where I can not only explore and think about those things that personally excite me, and nudge others in the general direction of those things. And I don’t take one second of it for granted…ever. Maybe along the way I’ll change someone’s mind about something or put them on a course to create something important or exciting. That’s all any of us who get involved in the arts can really hope to accomplish — the money is temporary, we’re temporary, nothing lasts. But as long as the earth keeps spinning the whole point of expressing your love for things is you hope to influence someone else who will express their love for things who will go onto express their love for things… Look, I know I’m only here for five minutes. And I know I’m lucky to have amazing children, great kids, a great wife who has starred in both my films, good friends, and a good gig. My only real goal beyond that is after I’m gone I hope I’ve left enough of a little trail of breadcrumbs that someone will pick up on and maybe have some influence on their journey. As cliché as it sounds, that’s all I care about at the end of the day.