Welcome to Tales From the Metalnomicon, a new twice-monthly column delving into the surprisingly vast world of heavy metal-tinged/inspired literature and metalhead authors…

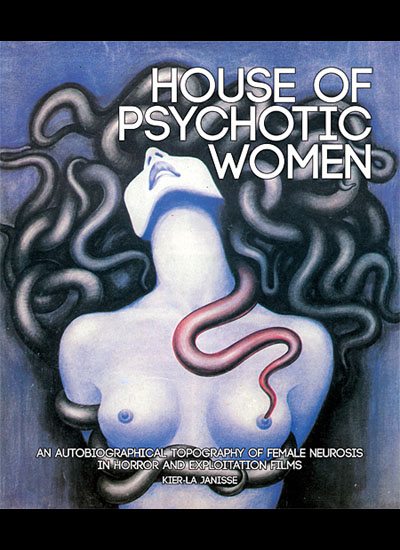

In her exquisitely rendered, frequently disquieting, always edifying new book House of Psychotic Women: An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis in Horror and Exploitation Films well-respected critic, festival programmer and King Diamond devotee Kier-La Janisse writes of a childhood visit to a garage sale during which she pleads with her mother for the quarter necessary to purchase a copy of Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws.

“She conceded, with the caveat that she be allowed to read it first to make sure it was ‘acceptable reading’ for a child my age,” Janisse writes. “I expected this. What I didn’t expect was to get the book back marked up with a ballpoint pen, words changed, and entire pages scribbled out. I still think this book is my mother’s masterpiece of repressive zeal.”

Janisse continues:

Of course, the ink didn’t deter me: If I held the pages up to the light I could read through it. Like all things buried, these dirty truths come to the surface one way or another.

House of Psychotic Women is not unlike that light. Its lushly illustrated pages illuminate and elucidate, summoning hitherto obscured patterns and subtexts of both classic and obscure entries in the “apocalyptic hysteria” celluloid subgenre into view, deepening appreciation for those films a given reader has seen, piquing interest in the dozens they haven’t. (The appendix compendium will almost certainly blow the minds of most outré junkies.)

“I was always drawn to these films, but for a long time I never gave it much thought beyond, ‘Yeah, I like these movies with crazy women in them,’” Janisse tells Decibel. “Once I started writing the book, though, it was striking to me how the central problem of so many of the women in so many of these films is the same problem, which is issues of identity — basically, the expectations others manufacture for women, the expectations they manufacture for themselves, and then the consequent ways they act out when the inability to meet those expectations becomes clear.”

Janisse’s analysis is, beyond question, erudite and savvy. But it is also uniquely powerful, in no small part because of her decision to intertwine her own harrowing life story into the wide-ranging dissection/exploration — an approach she at first shunned, despite the counsel of friends who noted how animated she would become making precisely those connections in private conversation. Instead, Janisse initially focused on her long-standing original plan — i.e. a series of essays on seminal films (Possession, The Brood, The Entity) and actresses (Mia Farrow, Mimsy Farmer) alongside ruminations on vital/brutal titles she’d unearthed via underground distributors like European Trash Cinema — until a structural epiphany arrived, oddly enough, in the form of Sandy Balfour’s cryptic crosswords memoir, Pretty Girl in Crimson Rose (8): A Memoir of Love, Exile, and Crosswords, a book which, despite a lack of references to, say, Repulsion or Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, nevertheless offered a roadmap for marrying niche interests to a tale of personal evolution.

“Once it started becoming personal I knew it would probably have to be really personal, especially if I’m talking about mental illness and film,” Janisse says. “I couldn’t just say, ‘Yeah, I relate to these characters because my mom was crazy and I’m crazy.’ I felt like I had to tell the uncomfortable stories that would illustrate why my brain works the way it does…and why it doesn’t always make sense to other people, even if it mostly makes sense to me.” Of course, such a public display of honesty carries its own hazards: “First of all, your story is not just your story. It’s also the story of everyone else in your life. So I had to start navigating the ethical responsibilities of the fact that exposing myself meant exposing all these other people.”

Thus, family members named after characters on The Love Boat; fellow group home residents re-christened in homage to The Facts of Life; and a profund (and perhaps permanent) personal vulnerability.

“It’s scary that if anyone ever wanted to manipulate me, everything they’d need to do it is in this book.”

Many extreme music disciples will doubtless find much to relate to in House of Psychotic Women—and not just because several chapter headings resemble song titles off a power-violence record — e.g. “Wound-Gatherers,” “Heal Me With Hatred,” “You’ve Always Loved Violence.” Janisse captures well the strange allure of chasing ever-greater, more esoteric forms of chaos and brutality down the cultural rabbit hole*, so perhaps it come as no surprise that her love for metal and hardcore punk makes several cameos over the course of the book, from her discovery of Alice Cooper — “I would always take the needle off before ‘I Love the Dead,’” Janisse recalls, “until I got older and built up the courage to dare myself to listen to it” — to introducing Lost Boys-loving girls at her group home to the more subversive pleasures of Rock N’ Roll High School.

“Getting into aggressive, heavy music…I just liked the fact that it pissed everyone off that I listened to it!” Janisse, who also contributed to the much praised DESTROY ALL MOVIES!!!: The Complete Guide to Punks on Film, says. “Everyone hated it, everyone was afraid of it. My mother took away my Sabbath records because she was convinced they were satanic. I felt at odds with everything and that music at that time was very important to me…I always make fun of things like Quincy, M.E. punk rock episode, but now that I’m older I realize, No, that’s actually what it looked like to everyone!”

“All of this extreme culture is helping to fill a void left by something else,” she adds. “We need that chaos sometimes to establish contact.”

Janisse is currently at work on a book about “children’s programming in the counterculture era” entitled A Song from the Heart Beats the Devil Every Time, dreaming of creating her own breakfast cereal (“I’m a big fan of cereal and cereal culture—I don’t know if cereal culture is a real thing but…I guess I’m saying it is!”), serving as FANGORIA magazine’s Web Director (archive; full disclosure: Janisse has published a handful my reviews), and continuing her expansive programming work, including, recently, a popular 1960s-1980s Cartoon Party.

“I’ve been stunted in my childhood for a long time, so I’m just trying to find ways to do something constructive with that,” Janisse laughs, adding, “My personal obsessions will always be fueling whatever project I’m working on, but I want House of Psychotic Women to be the last thing I do for awhile — maybe ever — where I’m at center of it all.”

A reasonable request, surely, after such a command performance.

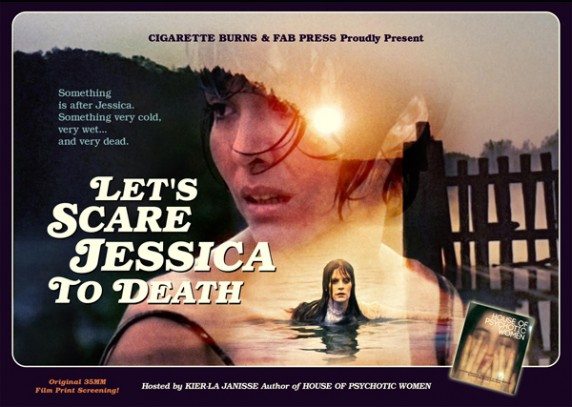

Kier-La Janisse will be introducing a 35mm screening of Let’s Scare Jessica to Death at London’s ICA Gallery on Thursday, April 18th. Keep up with Janisse via Twitter or her official Big Smash Productions website.

* A short relevant excerpt on this point from the introduction to House of Psychotic Women:

When I first started edging into film writing in the mid-90s, I was all about girl-power; how horror films (even slasher films) were empowering to women, how most horror films were about men’s anxieties concerning the nature of femininity and female sexuality, gender relations, castration anxiety — all this great, meaty stuff. I saw positive female representation in everything, no matter how ostensibly reprehensible the film’s politics. For a female horror/exploitation film fan, that’s a great place to start; certainly more productive than denouncing the genre altogether as some counter-revolutionary, misogynistic exercise in populist entertainment. But I often found myself generalizing, and the brevity of magazine articles allows for that, even encourages it. I wanted to explore neurotic characterization as comprehensively as I could, but I also didn’t want to write a dense book of horror theory, as my interest in academic writing has diminished significantly over the years. I also knew that if I started leaning too much on Freud and Lacan I’d be out of my depth. I needed to focus on what I know: namely, that the films I watch align with my personal experience in that every woman I have ever met in my entire life is completely crazy, in one way or another. Whether or not that’s a disparagement is part of what I aim to explore in this book.