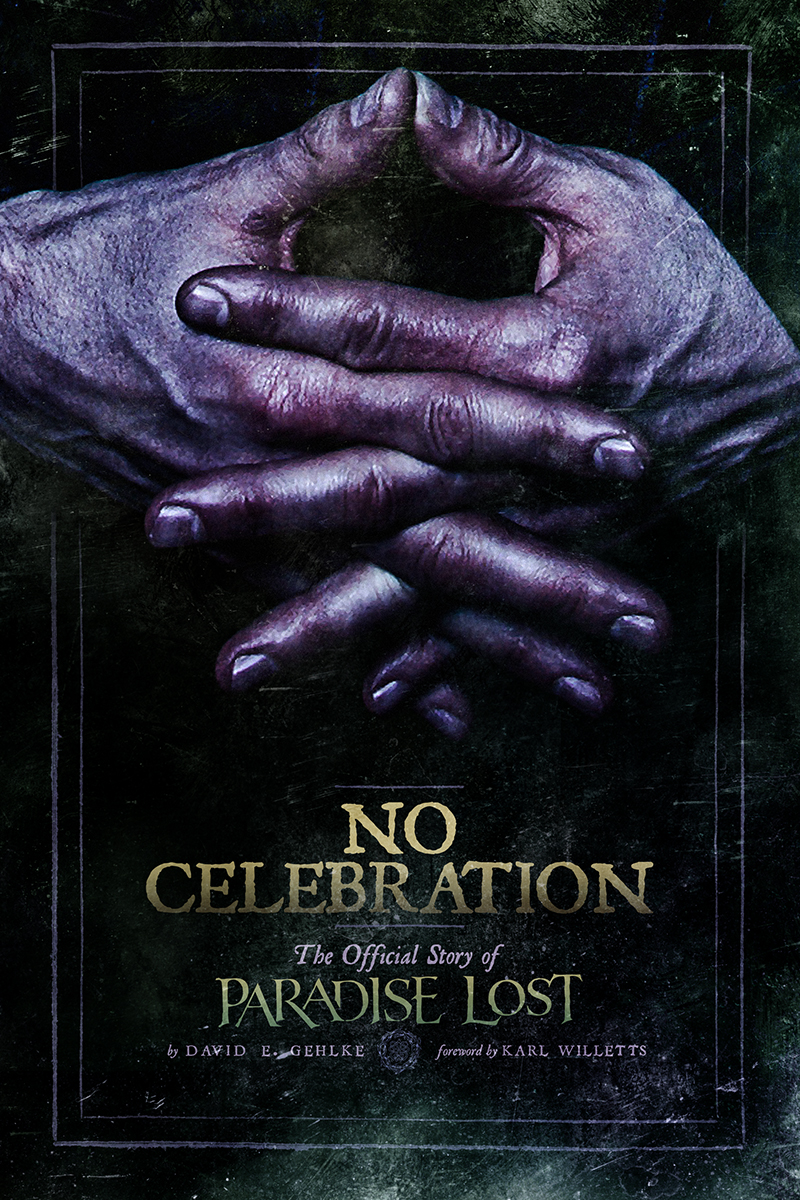

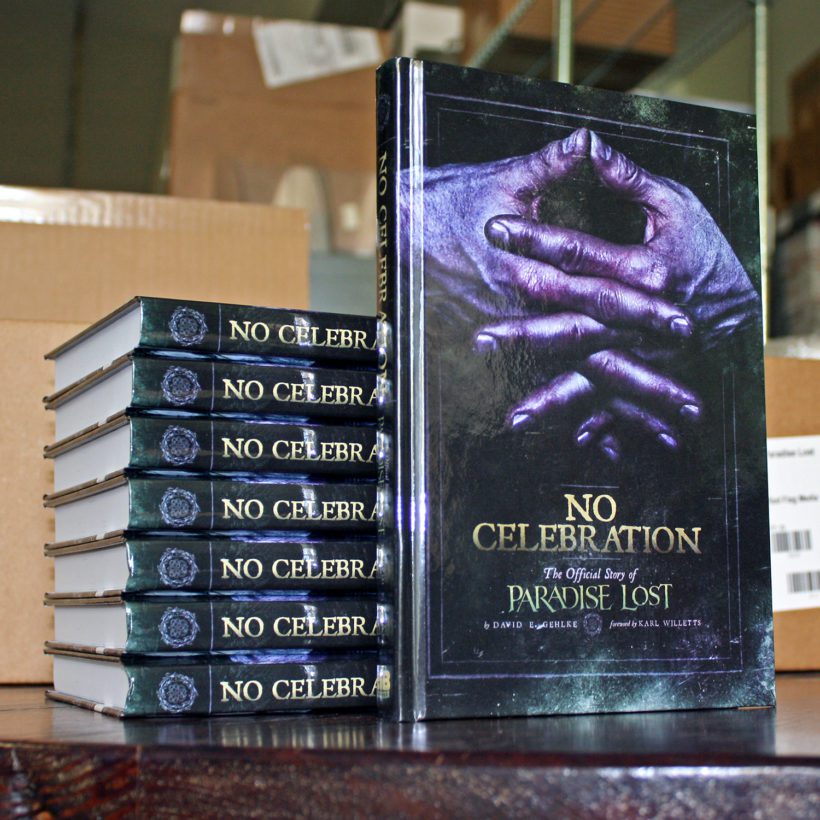

Decibel Books’ No Celebration: The Official Story of Paradise Lost is out today. Well, technically, since it’s a Decibel webstore exclusive, it’s not “out” anywhere but the Decibel office, BUT our pre-orders are officially shipping today, and to, um, celebrate, we’re happy to share this exclusive excerpt. The following piece from author David E. Gehlke’s 306-page PL history focuses on the band’s 1997 record, One Second, the Brits’ first step away from underground metal. It also serves a tribute to Music for Nations’ founder Martin Hooker, who passed away earlier this month and is featured heavily in this excerpt.

As with the previous three occasions he’d received a mixed and mastered version of a Paradise Lost album, Music for Nations’ Martin Hooker wasted no time in popping One Second into the stereo at his London office. One Second was to be their priority summer 1997 release, and while most labels try to avoid releasing high-profile albums at this time of year, Hooker figured Paradise Lost was a safe bet. He gave the tracklisting a cursory glance, plopped his feet onto his desk and listened with anticipation.

He was shocked at what he heard.

As was their practice, Paradise Lost gave Music for Nations no indication how the album was going to sound. Hooker placed an infinite amount of trust in Paradise Lost, but he, like everybody else at Music for Nations, was expecting something along the lines of Icon and Draconian Times. When it became clear by the album’s midway point that it wasn’t to be, Hooker’s shock turned to disappointment. He knew right away Music for Nations would have problems promoting the album.

And so began the rub with the “dark rock” version of Paradise Lost. Music for Nations was no stranger to promoting music of different varieties; their handling of Frank Zappa’s back catalog became a significant source of income in the 1990s. But Zappa had an audience that defied description, enabling Music for Nations to spread its marketing and promotion resources accordingly. When Hooker started to discuss the promotional plan for One Second with head public relations rep Liz Wells, the two ran into a brick wall. Up until that point, Paradise Lost was an easily-identifiable metal band. Hooker and Wells were gravely concerned they wouldn’t be able to convince the metal press to cover a band who were now starting to disown the style. Furthermore, they were worried that alternative music outlets would refuse to cover Paradise Lost because of their metal background. “One Second really wasn’t anything new for us,” says Hooker. “We’ve had success with non-metal music — just look at Angry Anderson’s ‘Suddenly’ song, which was a top-3 hit. However, getting the press interested was very difficult. They were looking forward to more of the same, just like we were. We sort of went by the idea that if you’ve got a great band, you have to hope that they know their fans better than they do.”

A key factor in this was the Internet was still in its infancy and was nowhere near the source for obtaining music it would eventually become. The written word still carried an infinite amount of weight, leaving the press to guide would-be buyers and longtime fans through One Second’s shades and shapes. “People were still reading text from magazines and relying on radio,” says Aaron Aedy. “That’s the only way people could form their opinion back then. It was really up to writers to describe the band succinctly. They could position it so people could say ‘All right, I like that kind of thing, so I might try them out.’ Sometimes reviews only have three paragraphs and you’ve got to describe the band and the album in all that, so pigeonholing was a big thing. And pigeonholing, it sounds like a bit of a dirty word, but I totally understand why it was there and the bands hate it, but there is a reason for it. The public needs to know if it’s something they might be into. They can’t be bothered with you leaving them a load of waffle.”

Hooker and Music for Nations were lukewarm toward One Second and doubted its commercial viability. Previous Music for Nations promotional campaigns saw the label put on an all-out assault on the press with studio reports and countless photo sessions. For One Second, the label played off the album’s title: They created stopwatches and an alarm clock, which, according to Hooker, “cost a fortune.” Their efforts slowly started to pay off. As expected, the album was a hard sell to the metal scene, but it debuted at number eight on the German charts; seven in Finland and five in Sweden, with Paradise Lost manager Andy Farrow estimating a total of 40,000 in sales.

“I was certainly keen for the band to not change their core style too much or too quickly,” says Hooker. “If one minute you’re dressed in black with long hair and then suddenly you turn up playing a different type of music, with short hair and suits, the fans have trouble dealing with it. The One Second album happened at the latter part of my time at Music for Nations and I have to admit that it was one of my least favorite Paradise Lost albums. I wasn’t a massive fan of the new style and to be honest, it proved much more difficult to sell.”

Music for Nations acquired Peaceville Records in 1995, giving them access to the entire Paradise Lost catalog. An obligatory career-spanning compilation, Reflection, was released in October 1998, culling from each of the band’s studio albums. It also included the keyboard-heavy remix of “Forever Failure” that was used for its accompanying music video, “Rotting Misery” in dub, as well as three live cuts taken from the band’s January 1998 performance at Shepherd’s Bush Empire. The Shepherd’s Bush Empire show was also professionally shot, culminating in the One Second Live DVD, which was the band’s last release for Music for Nations.

One Second was Paradise Lost’s best-selling album until Draconian Times was re-released in 2011. While the album failed to produce a hit single (“Say Just Words” notwithstanding), it was the necessary and successful pivot-point in Paradise Lost’s career. Their contractual obligations now fulfilled, Farrow started lengthy discussions with EMI Electrola’s Managing Director Peter Burtz and Vice President of International, Lothar Meinerzhagen.

“A lot of labels were looking at the band,” he says. “It was ironic. First, the biggest thing is, if you sign to a major in Germany, it doesn’t guarantee release in the U.K. Every time I have signed bands in mainland Europe, I’ve been aware of that. That’s why as a manager, you have to get on a plane and go to places. Basically, Chumbawamba was signed to EMI and was a Leeds band; so was New Model Army. Since Lothar was the guy who signed Chumbawamba and was the head of International for EMI Electrola, I got in touch with him. He was definitely interested in Paradise Lost.”

Hooker cautioned Farrow that moving Paradise Lost to EMI wouldn’t have much of an effect on their career. Rather than being the proverbial big fish in a small pond, he suggested Paradise Lost was about to become the opposite and might struggle with not being a priority. “Having worked for EMI for six years, I knew first-hand that they’d be totally wrong for Paradise Lost,” says Hooker. “Naturally, Andy was free to have his own opinion as to what was best for the band. I believe we did make a counteroffer, but they were keen to see what life on a major label would be like. The hope was EMI could take them to another level.”

A few years earlier, the members of Paradise Lost looked on with interest as their friends in Carcass, Cathedral and Napalm Death had their quick run in major label land as part of Earache’s licensing deal with Columbia Records. The results were largely mixed; the deal did little to further the bands’ commercial prospects, but Paradise Lost didn’t sound like any of those bands. Even though Music for Nations often spared no expense when it came to Paradise Lost, the allure of major label budgets was too much to resist.

“I think we could have probably gone further with Music for Nations if we just hadn’t been so into the idea of getting the bigger budgets,” says Greg Mackintosh. “We wanted more recording budget, more video budgets, access to bigger things, I guess. At the same time, we were about to become a smaller fish. We weren’t that on Music for Nations. We certainly underestimated the power of that.”

“Music for Nations did not do anything wrong at all,” adds Aedy. “They were an amazing label for us to be on. It would have been interesting to see what they’d have done with the records that came after One Second. Naively, we thought by going to a major label we were going to move to the next level. Everyone was expecting this big ascendency, so we thought going to a major label was the way to do it.”

Paradise Lost officially joined EMI Electrola on a two-album deal in the fall of 1998. The band had started the decade on the DIY, one-man operation of Peaceville and were now sitting on a major label with the financial wherewithal that could offer them the budgets they felt they deserved. Still, the parting was bittersweet — leaving Music for Nations was difficult for Paradise Lost. The same applied for the label, who, not too long after losing Paradise Lost, would go through their own difficulties when Hooker left in 1999. Music for Nations would last for another five years under the direction of Andy Black before closing shop in 2004.

“We were obviously disappointed to lose the band, but it’s one of the difficulties of being an independent label,” says Hooker. “As soon as you have success with a band, there’s always a major label lying in wait hoping to snatch them up. The fact that they weren’t interested in the band while they were on the way up never seems to matter. We’ve had a few bands leave us to sign to majors. With the exception of Metallica, they were all disasters.”

Order a copy of the limited edition hardcover of No Celebration: The Official Story of Paradise Lost right here.